Yet another guide to media stocks: The Intro and cord cutting

For the past year, whenever someone has decried that the bull market has run forever and there's nothing cheap out left to look at, I would always respond with, "I don't think that's true. Most of the legacy media stocks (CBS, FOX, etc. disclosure: I have a small position in CBS) are trading at 8x P/E or less. The car companies (GM, Ford, etc.) are trading for 5-6x EPS. Most mega-cap banks (WFC, JPM, GS) are trading for small premiums to book and 10-12x EPS. I'm not saying any of them are undervalued, but they are certainly cheap, and I wouldn't be surprised if there's value in one of those sectors somewhere. Either in a 'baby thrown out with the bathwater' situation (i.e. the whole of the legacy media sector is worthless, but one or two of the stocks within the sector is a gem) or just a whole sector has been discounted." (note: you can find links to all of the pieces in this series here) Anyway, over the past few months, I've spent lots of time looking on and off at legacy media companies. If you read this blog, I'm sure you're not surprised: my largest investment is in a cable company, and media companies are probably the stocks that I find the most interesting. However, I've been a bit hesitant to flesh out my thoughts and put them onto the blog. Part of that is there's incredible analysis out there: Liberty Investor Day is always a masterclass in the media sector, and Matt Ball's (formerly of redef, now at MBVA) stuff is incredible. Honestly, my stuff pales in comparison to their's. The second reason I was hesitant is it's kind of a daunting task: the media sector is huge, and trying to put down thoughts on multiple pieces of the sector would require a lot of writing. The final reason I was hesitant is because it's easy to look silly investing in the media sector, particularly the legacy side: consider Lionsgate (LGF; disclosure: I have a small position). The stock is down ~50% over the past year, and it's EV currently sits at <$5B. That's pretty incredible given CBS bid ~$5B for just Starz (which Lionsgate owns) earlier this year. Yes, an informal $5B bid for Starz is not the same a signed deal, but still: for the whole company today to be worth less that one unit was offered a few months ago underscores just how quickly things can move in the space currently. So I was a bit hesitant to put my thoughts to paper. But my honeymoon's coming up in the back half of December, and I wanted to take on a bit of a project before then. That, plus the combination of Liberty's investor day in November and the pending close of the CBS / Viacom merger, inspired me to write a media piece. The overall objective of this piece is simple: I want to walk through my thoughts on a bunch media stocks / components. Remember one thing when reading this: I'm a buyside investor, and the general endpoint for when I research a stock is do I want to buy (or sell... or short) that stock, and everything has a price. So, if you asked me what has a rosier future today between Netflix and CBS, I would tell you Netflix. But CBS's stock trades for <8x earnings, while NFLX's trades for.... a much larger number (Bloomberg tells me its 100x P/E, though I think that includes some significant addbacks). If you ask me if I'd rather invest in CBS at 8x EPS or NFLX at >100x, I think CBS is the better bet. If NFLX traded for 40x P/E and CBS traded for 8x, the decision would probably be different. So just remember: everything has a price, and the purpose of this series is to both walk through the media sector while keeping in mind the prices / valuation the market is currently offering. I also think that positions me a bit differently than a lot of the other writers I talked about before: I'm not some person just opining and strategizing on the sector; I'm actively looking to invest (or not invest!) and make money in the sector (or not!). And I'm not Liberty, who have stakes in a bunch of different places in the media sector and can't be completely honest about how they feel (how do you think you'd feel if you were the CEO of a Liberty company and Malone came out and said the whole sector was worthless? Or do you think Liberty would get a good price in acquisitions if they were letting everyone know the honest trust about how they felt for every sector?). So that's the intro / overview. But I also wanted to cover one more thing before diving into the individual sectors: cord cutting. It's impossible to talk about the media sector without having some view of cord cutting, and I find a lot of the non-media "expert" people I talk to don't fully understand the dynamics of cord cutting, so I wanted to cover it here. Cord cutting is, at its most basic, pretty simple: households who used to subscribe to the legacy cable video bundle are increasingly dropping that package and choosing to just buy broadband from their cable provider. For video, they're choosing some combination of Netflix, free youtube videos, or maybe some other DTC products (like Disney+, HBO Go, etc.). The dynamics of cord cutting create a really vicious negative flywheel as it comes apart. The best way to show this is with a really simple model. Consider a world where there are just three channels: Sports, News, and Entertainment. Each channel costs $10/month/sub. The whole cable world consists of just 10 customers, and each customer gets value from each channel in a different way. So customer 1 values sports at $50/month, news at $12/month, and entertainment at $11/month. In total, the value is worth $73/month to him, yet he only pays $30/month, so he gets $43/month of value from the bundle. In contrast, customer 2 doesn't care about sports, but he really likes news and entertainment ($26/month). The bundle is worth $52/month to him, yet he only pays $30/month, so he gets $22/month in value from the bundle. I've created a world with 10 hypothetical customers and 3 channels below (Some notes: The box shows what each customer values each channel at. The bottom bold is the total value that customers put on each channel; the right bold is how much each channel values the bundle in total. The cost is the cost of the bundle, and the right shows how much excess value each customer gets from the bundle. If it goes negative, the customer drops off).

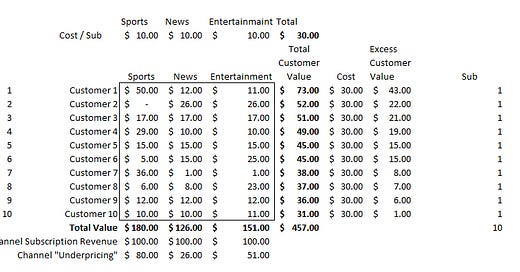

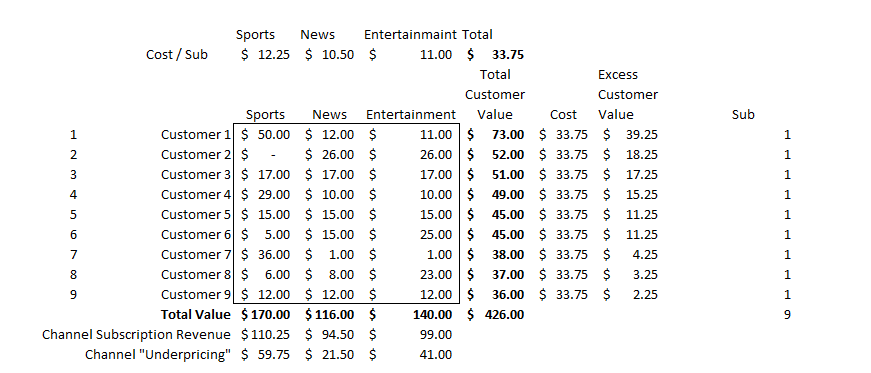

Now let's go to year two of the model. If you're the sports channel, you look at this and say "woah, I'm delivering way more in value than I charge". The next year, you've going to go to the cable channel and demand they increase what they pay you, noting (rightfully) that you deliver $18/month/sub in value, more than any other package, and you only get paid $10/sub. Of course, news and entertainment are each going to argue that they deliver more in value than they get paid as well. An important point to note here: each channel is raising their price, but none of them are actually increasing the value they deliver! Let's pretend that, after some negotiation, sports is going to increase their fees to $12.25/month, while news goes to $10.50 and entertainment goes to $11. The total cost of the bundle is now $33.75/month.... but that's above the value that customer 10 is willing to pay for the bundle (it's only worth $31/month to him), so he's going to drop out of the bundle. The cable system now only has 9 subscribers, but each of them pay $33.75/month. Our new hypothetical cable system is below

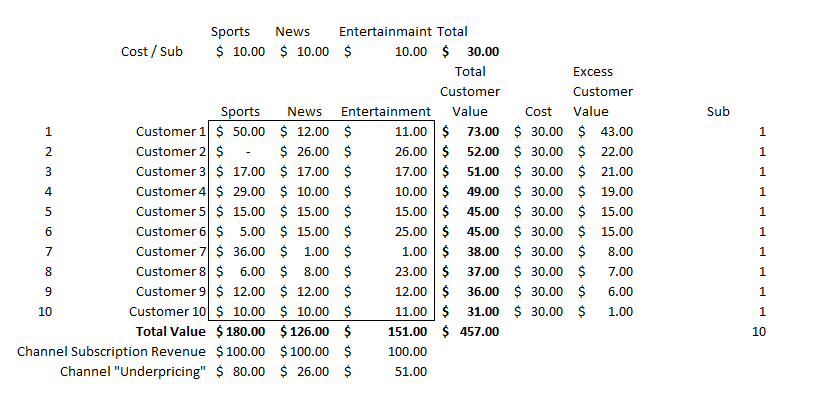

Well that's kind of interesting, right? Sports revenue is up nicely year over year despite losing 10% of their subs. Entertainment and news both saw revenue declines despite nice pricing power. That sets up for a strange year three, as each channel can go back to the cable channel and point out that they're still delivering value well in excess of what they're charging. Let's say sports manages to negotiate an increase to $14/month, while news goes to $11 and entertainment to $12. The bundle now costs $37/month; customer 9 only valued it at $36/month, so he's going to drop out. Our new system is below.

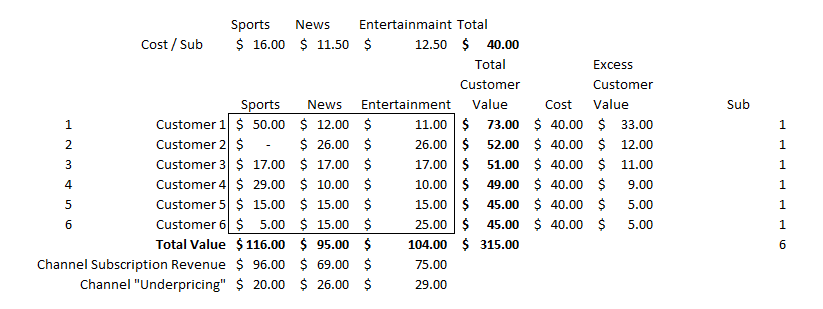

Sports managed to slightly grow their revenue in year 3, while the other two channels saw slight declines. You can probably see the issue now: the bundle is on the verge of unwinding. It's in each channel's individual best interest to try to raise pricing, but it will destroy the collective whole. Just to play the story out, let's say in the next round of negotiations sports goes to $16/month and news and entertainment get $0.50/month increases (to $11.50 and $12.50, respectively). The bundle now costs $40/month. Customer 7 and 8 drop out. Every channel reports mammoth declines in revenue, yet every channel can still go back to the cable companies and show that they are delivering a lot more in value than they are charging their customers. Notice that the excess value delivered by our news channel has actually increased year over year because the two subs they lost didn't really care about news. Next year, News could rightfully demand an even large increase per sub despite the fact they are not delivering any more value and doing so will help accelerate the blow up of the bundle. The bundle has broken.

Obviously this is a super simplified example, but I think it illustrates the dynamics of the cable bundle pretty clearly. Each channel can (for the most part) claim they deliver more value than they charge, so each channel can rightfully get a price increase in each negotiation. However, the value delivered to customers of the bundle never changes, so as the overall bundle's pricing increases it continues to price out marginal subs. Each channel is stuck raising prices just to try to maintain a flat revenue base, which causes the price of the bundle to rise even further and pushes even more people out. In fact, if anything, this example painted too rosy a picture for the cable channels. The price of content across the board is rising: sports rights continue to generate huge premiums when they come to the market, and the cost to make premium content is exploding as Netflix and a host of other new competitors are willing to pay up for the best talent. So the cable channels face a rising cost base in the face of falling subscriber numbers. This problem is particularly acute for ESPN; in fact, I call it the ESPN problem internally. ESPN committed a huge amount to sports rights at a fixed cost (actually, likely rising as they have yearly pricing increases baked in). Say that ESPN committed $1B/year to the NFL. A few years ago, ~100m households subscribed to the payTV bundle (and basically all of them had ESPN), so the NFL cost ESPN ~$1/sub/year. Today the payTV bundle has something like 80-85m subs, and that number is dropping something like 6-8% every year. So today the NFL rights costs ESPN ~$1.25/year/sub, a 25% increase! What happens if in a few years we've dropped from 80m to 60M? It's not hard to see a world where cost cutting has driven the cost per sub ESPN pays for sports rights to be twice as high as they projected. The only solution to the ESPN problem is to try to take more pricing.... which further accelerates cord cutting. And we haven't even mentioned advertising revenue for the cable bundle yet yet: remember, most advertising revenue is paid out based on number of people watching, so as more people cut the cord and ratings decline, advertising revenue will eventually have to go lower.... which will force the channels to lean on pricing power even more if they want to keep up with their rising cost structure. Plus the alternatives continue to get better: twenty years ago, if you didn't subscribe to the cable TV bundle, you effectively couldn't watch TV. Today, if you don't subscribe to cable TV, you can pay ~$15/month and get a Netflix subscription and have access to more TV than you could watch in a lifetime. Yes, you won't have sports and news with Netflix, but that's the point! Twenty years ago you had to pay for the Sports and News if you wanted to watch any TV; today, there are options for you if you don't need those. Anyway, bottom line: for a whole host of reasons, the price of the bundle will continue to rise. However, the value of each individual channel doesn't ever really change, so overtime the bundle will continue to price out the marginal sub. As each sub gets priced out, each channel will have more incentive to try to raise their pricing to meet their cost burden, creating a negative flywheel that will eventually implode the TV bundle. To be continued in part 1...