Contingent Value Rights (CVRs) are a quirky little area of the market, and we’ve seen a bunch of them in recent M&A deals (to list just a few off the top of my head, ABMD, ALBO, CINC, CNCE, and OPNT all had CVR components to their deals; all of those are pharma deals, and CVRs overwhelmingly come from pharma deals, but you can see them outside of pharma. For example, look at the recent RFP deal for a non-pharma CVR merger).

As I’ll detail in this article, I think there’s an argument to be made for some inefficiency / potential alpha in the CVR market…. but, as I’ll also detail, there are huge risks that I think often go overlooked. And the risks extend far, far beyond the fact that CVRs are generally binary bets (though that is certainly a huge part of the risk!).

In fact, those risks are exactly why I wanted to write something on CVRs. Too many times I have someone email me something along the lines of, “this is the best arb ever! I’m buying this below the cash deal price, so I’m getting paid to buy the CVR!” and when I run the math I think they’re taking on way more risk then they realize (at the start of this article I mentioned ~6 recent CVR deals; of those six, I personally thought three were easy passes, one was “bleh”, one was quite attractive, and one was extremely attractive…. though obviously that high level analysis would change as the prices moved and the process played out!).

So in this article I wanted to cover why I think CVRs are so interesting, as well as some of the risks I think investors might be missing when they’re looking at CVRs.

My hope with the article is that it’s just helpful for investors in thinking through the risks and opportunities when it comes to CVRs, but my secondary sneaky hope is that if anyone is looking at a new CVR they think is interesting through the lens I’ll present and wants to send the idea my way for review I’ll have helped create an interesting pipeline of idea filters for myself (I believe I catch / look at every CVR that comes out, but it’s always helpful to have an extra pair of eyes on them, and my DMs are always open!)……

Anyway, I’m going to do this whole article as a mini-case study from a recent CVR, the JNJ acquisition of ABMD. I think that deal shows both the advantages and risks of CVRs, and analyzing it will help make the points I want to make better than I could by talking in the abstract.

Let’s start with some background. JNJ announced a deal to buy ABMD for $380/share plus a nontraded CVR* on November 1, 2022. The CVR would pay up to $35/share and had three different milestones (for the complete CVR initiate, a milestone is something that needs to happen by a particular date for a CVR to make a payment. The most common is a FDA milestone, which calls for a payment if the FDA approves a product before a certain date). Per the merger press release, the three milestones for ABMD consisted of:

$17.50 per share, payable if net sales for Abiomed products exceeds $3.7 billion during Johnson & Johnson’s fiscal second quarter of 2027 through fiscal first quarter of 2028, or if this threshold is not met during this period and is subsequently met during any rolling four quarter period up to the end of Johnson & Johnson’s fiscal first quarter of 2029, $8.75 per share

$7.50 per share payable upon FDA premarket application approval of the use of Impella® products in STEMI patients without cardiogenic shock by January 1, 2028; and

$10.00 per share payable upon the first publication of a Class I recommendation for the use of Impella® products in high risk PCI or STEMI with or without cardiogenic shock within four years from their respective clinical endpoint publication dates, but in all cases no later than December 31, 2029.

For the CVR curious, why don’t we start by talking about the potential upsides and attractiveness of the CVR, why some alpha could be hidden here, etc. before turning to all the potential risks.

The first thing that has to been mentioned is just the opportunity for a multi-bagger on the CVR. We’ll discuss CVR fair value in a second, but ABMD’s last trade before the deal closed was for ~$381/share. That implies a price per CVR of ~$1/CVR (the $381 trading price less the $380/share in cash that came with this deal). If the whole CVR paid off, the CVR would be ~35x on that ~$1/share CVR cost basis.

Now obviously that’s an enormous, enormous simplification that ignores plenty of risks. Every a CVR is a contingent value right; the contingent is there because something needs to happen in the future for the right to pay out and that might not happen. Plus, the payouts are deep in the future; the ABMD payouts likely would not be made until 2028 or 2029, so they need to be discounted back to the present. The bottom line is that you can’t just say “this is a $35 CVR payout and I’m buying it for ~$1”; you need to adjust for risks and the time value of money.

But I’d argue that even if you adjusted for that risk and time value, the CVR was still probably pretty attractive. If you read through ABMD’s SC 14D9, you can see ABMD’s financial advisor’s (Goldman Sachs) fairness opinion on p. 35. Goldman put the net present value (NPV) of the CVR at $16.96/share. I believe that NPV is just discounting for the time value of money, not risk-adjusting the payments (i.e. if a milestone is 90% likely to be hit, a risk adjusted valuation would value the NPV of that payment at 90% of its discounted value; if you look at p. 40 of CINC’s 14d9 you can see what the language around a risk-adjusted payout looks like). The proxy notes the board believes the “milestones are reasonably achievable”; reasonable people (pun intended) can differ on what odds “reasonably achievable” means a CVR is to pay out (I would personally say the term “reasonably achievable” means management thinks something is ~65% to play out and I’d probably discount them down to 50/50 when setting my own odds / adjusting for management bias; I put the term to a Twitter poll and clearly my followers are less trusting than me given almost 50% of people would set the odds at <50%!), but even if you take a really pessimistic view of the odds we can probably safely say that buying the CVR for ~$1 when the NPV is ~$17 is probably a pretty good discount (a price of $1/CVR implies ~6% chance of payout on a $17/CVR; I would guess even the most skeptical of investors would not guess a board used the term “reasonably achievable” if the odds were under 10%!).

Alright, so the ABMD CVR is/was probably a good deal at the implied levels before the deal closed. But it would have taken all of ~15 minutes of reading the filing to see what Goldman valued the CVR at and that the market implied price of the CVR was pretty cheap. If it takes that little work to identify the opportunity, how has it not been picked over / why does the opportunity exist?

I believe there are three reasons:

The “fair value” of the CVR I presented earlier is based on what the bank estimated the fair value as. You could argue two points there: that fair value is implicitly biased higher for a variety of reasons and that this fair value ignores the corporate buyer’s incentives to dodge the CVR pay outs (i.e. if the payout calls for FDA approval by June 30, the buyer has a ton of incentives to get the FDA to approve the drug a week later and thus not have to pay the CVR).

On the first point (CVR value is biased higher), the bank basically just takes the seller’s projections and runs a discounted cash flow to value the CVR. Maybe that results in something too optimistic; in fact, it almost certainly does. But I would just note that CVRs are generally done on big premium deals where the selling company has a single asset or just a few meaningful assets. The acquirer is basically underwriting and betting that the seller’s projections are more or less going to be right and the drug / asset is going to be a hit when they agree to the acquisition in the first place; if the buyer is wrong, they’ll have generally made just almost as bad a bet as the CVR holders did!

On the second point (buyer incentivized to miss milestones)…. well, yes, companies will absolutely (allegedly) play games to avoid CVR payouts, so you should probably build some “fudge factor” into these. But, in general, CVR payouts give investors and buyers decent alignment as long as they are structured properly to avoid timing or revenue recognition games. It’s not perfect, but a properly structured CVR generally works with a buyer’s incentive to see a product / merger be a success. Consider ABMD’s CVR; the first milestone calls for a $17.50/share payout if ABMD’s sales exceed $3.7B at any time from JNJ’s 2027 fiscal Q2 to JNJ’s fiscal 2028 Q1. If the products have not hit that sales level, the CVR can still payout at a lower rate of $8.75/CVR if the sales levels get it by fiscal Q1’29. Could JNJ intentionally try to lower sales to dodge that CVR payout or get to a lower payout number? Sure! But the high end of the CVR payout is ~$750m. ABMD’s products run with >80% gross margin; in order to game the CVR, JNJ would need to actively harm their >$16B acquisition in order to delay hundreds of millions of sales (and gross profits) plus face some potential reputational / legal risks from doing so. Greed can cause people to do crazy things, and maybe there’s some risk JNJ tries to delay a few sales if the CVR is right on the edge of a full payout or a discounted payout a quarter later…. but I’d guess all in JNJ is pretty aligned here.

JNJ would probably agree. Obviously no one is going to say “yeah, we structured this CVR so we had awful alignment and we can really game it out and screw CVR shareholders,” but here’s how JNJ put it on the ABMD merger call: “With the CVR, we were able to make an attractive yet disciplined upfront offer and use a CVR structure with simple clinical and revenue-based milestones to clearly align incentives, allowing both sets of shareholders to benefit from the potential upside performance of the business in the future”

So there is probably some “discount the bank valuation / don’t trust the buyer” issue going on here…. but even with that adjustment I’d argue the CVR was still attractive. Which brings us to the larger reason I think the opportunity exists: investor incentives. The first payout for the CVRs probably isn’t coming until 2027 or 2028. If you’re an analyst at a merger arbitrage fund in late 2022 and looking at ABMD, the CVR is effectively worthless to you. There’s basically no chance you’ll be at your current fund by the time the CVR pays out. The average timeline for an analyst to be at a job is probably two to three years; given that job lifespan, there’s a good chance that you won’t be at the shop you leave your current fund for by the time the CVR pays out (i.e. you’ll have moved jobs at least twice before the payout). So, if the CVR pays out, you’ll see no personal benefit. But, while you’re still at your current fund, you will have the hassle of needing to explain the CVR position to your portfolio manager, and then the monthly hassle of needing to talk to your accounting team and explain how to value / handle the CVR every month (remember, the CVR is non-traded, so it’s an illiquid mark but every fund is going to require a monthly or at least quarterly valuation of the CVR). As an analyst, there’s simply no upside to putting the CVR trade on, but there is a heck of a lot of downside and hassle to getting it put on!

On top of that hassle, the net capital outlay to get access to the ABMD CVR is insane. The last day of trading, ABMD went out for ~$381/share, implying a fair value of the CVR of $1/share, or ~0.26% of the share price. Let’s say you decided to make the CVR a 1% position. You would have needed to put more than 300% of your portfolio into ABMD on its last day of trading in order to get ~1% position in the CVR. I always say “nothing on this blog is investing advice,” but it basically goes without saying that you probably shouldn’t put 300% of your portfolio into a single position…. though, now that I think about it, I’ll reiterate “nothing on this blog is investing advice” and go ahead and point you to our legal disclaimer.

So put yourself in the position of an analyst at your average merger arbitrage fund. To “put on” the CVR, they need to go do a ton of work on the CVR to justify the valuation to their portfolio manager. Then they need to argue for getting the CVR in the book, and they’ll need to talk their portfolio manager into sizing the position up. If their portfolio manager is bold, they’ll put maybe 5-10% of the fund into ABMD, which will result in a….. ~0.02% position in the CVR (and, again, that’s if the portfolio manager was pretty aggressive!). Then, the analyst will need to work with the back office every month to value the CVR. All that effort, and by the time the CVR plays out the analyst likely won’t be at the same fund. So the fund will get a small, small profit mark up if you assume the CVR successfully plays out, and the analyst won’t even be around to benefit (and, even if he was, even a 35x is so small at those levels there’s no guarantee he’d be rewarded for a position put on years ago!).

Bottom line: there’s just not a big buyer base for the non-traded CVRs, so you can see why they might trade a little wide of fair value / with some risk-adjusted alpha inside them.

At this point, I think I’ve covered the upsides to investing in CVRs. Yes, they’re binaries, so you risk a zero in them…. but they offer (non-correlated) multi-bagger potential, and you can point to obvious reasons for them to be mispriced / be a potential source of alpha given the buyer / capital issues.

But let’s switch over to talk about the risks to investing in CVRs. Because they are large and, in my opinion, often overlooked.

Let me start with the smallest risk I think people overlook, because it will help transition into the largest risk.

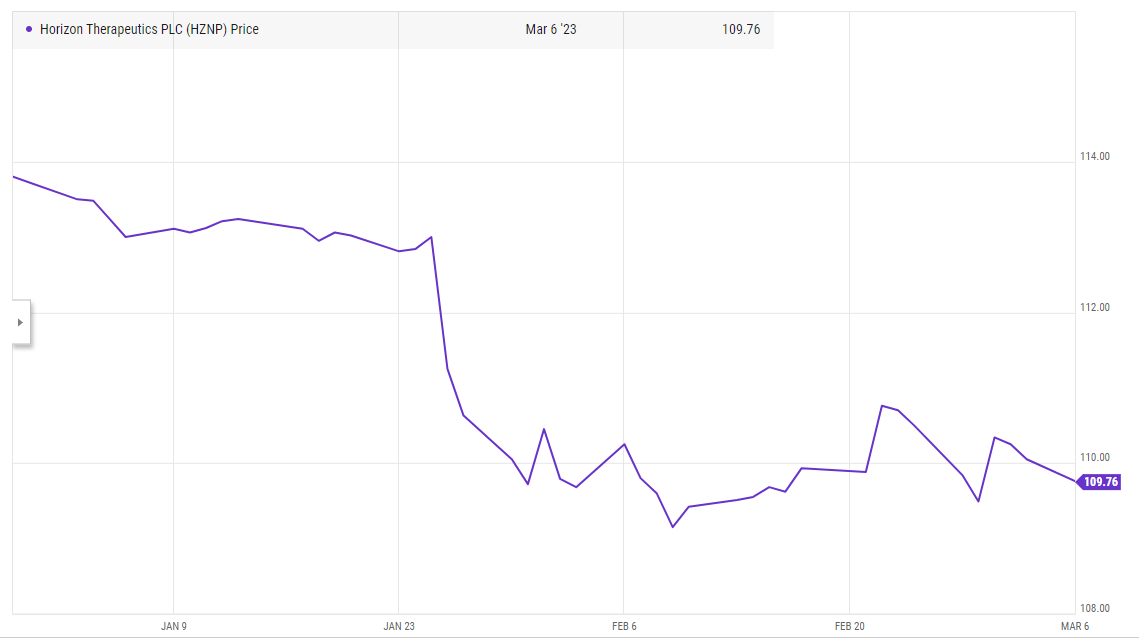

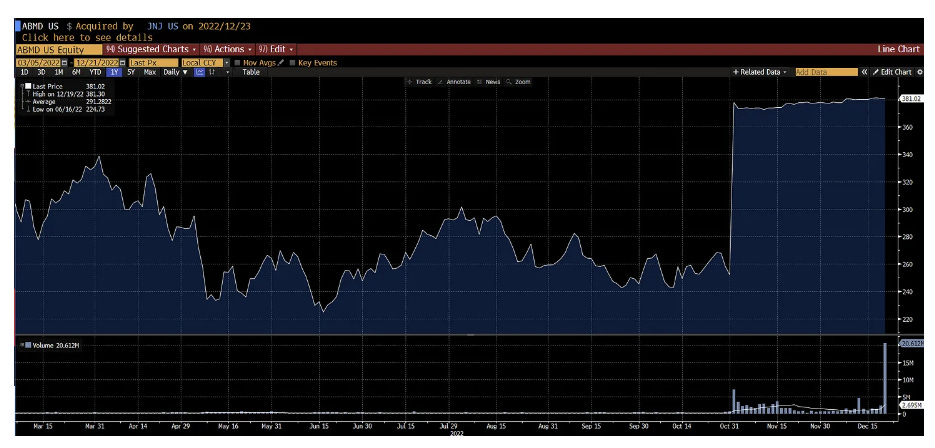

The smallest risk is simply timing. Most people emailing me about the “free” ABMD CVR were doing so in late November and early December. I’ve pulled up a chart of ABMD’s stock price around that time:

Notice that “massive” jump in early December that takes the stock from below the cash deal price to above it (I put massive in quotes because the Y axis is quite zoomed in; the stock only goes up from ~$378 to ~$381!)? That jump comes when JNJ discloses HSR had expired, which meant the transaction could close in near near future (HSR expired December 7 and the deal closed December 21). Basically, before that jump, there was a (small) chance the the DoJ would issue a second request on the JNJ / ABMD deal, and the market was pricing that into the stock. I don’t think investors who told me about the “free” CVR realized they were taking on DOJ extension risk!

What would have happened if the DoJ had issued a second request? Well, eventually the deal likely would have been approved, but the stock certainly would have traded down as the market started pricing in increased uncertainty over timing and some risk that the delayed timeline could lead to something truly unexpected happening that would break the deal. Investors need look no further than HZNP’s stock price this year to see what happens when a company gets an unexpected second request; HZNP is down ~4% on the year due to a surprise second request from the FTC. Yes, a 4% drop isn’t much in the grand scheme of things…. but when you’re buying a spread at <1% or playing for a “free” CVR, a 4% drop is an absolute disaster that probably shows you miscalculated your risk/reward, particularly given the size you would need to play to make the CVR into anything resembling a meaningful position.

That small HZNP drop on a simple delay shows the larger issue with these “free” CVR plays that I think investors miss. The downside to being wrong about the deal closing is enormous. If the deal breaks, the stock is heading down and heading down fast, and it’s often heading down much, much more than the you would expect.

Let’s stick with ABMD to show this. Consider the ~one year chart I showed for ABMD earlier:

JNJ’s bid for ABMD was at a very nice premium; $380/share in cash (plus the CVR) versus a pre-deal price of ~$250/share. If you just used $381/share as the upside to deal close (where the deal eventually closed / valued the CVR) and $250/share as the downside (the rough pre-deal price), you were paying ~98-99% implied probabilty that the deal would close before the DOJ decision came in.

Paying 98-99% is very, very high in a pretty uncertain world…. and I’d argue that number actually understates the odds you’re paying for the deal to close because the downside is likely to be much, much worse.

Why?

Well, for something like ABMD (or most of these CVR deals), the buyer is an absolutely solid corporate buyer. This is not some private equity or technobillionaire buying a company who is going to get cold feet if the stock market drops or the lending market gets rocky. Solid corporate buyers like JNJ are going to close regardless of financial conditions in the world. The way the deal is going to break is #1) if a regulatory agency rules that they cannot close or #2) if something absolutely terrible happens to the company in particular.

For case #1, I’d guess the downside to the stock is lower than the pre-deal price. Every small pharma company is eventually a M&A target for a larger company; if the DOJ rules that there is some anti-trust issue with a company getting acquired, the market is going to start taking some “acquisition candidate” premium out of the stock or, at the very least, factor in that the eventual buyers who the DOJ would allow are likely to be worse buyers with less synergies facing less bidding competition who will ultimately pay a lower premium.

But case #2 is the more pressing one here. The pharma market is large, and you generally know if a merger is going to be an anti-trust problem from the moment it is announced. Without an anti-trust risk, the other way one of these deals breaks is for something absolutely terrible to happen to the target company between deal announcement and deal close. There are lots of things to chose from here, but think about waking up to a headline that says “Company X under fire; investigative report shows product has traces of lead and has been tied to a 500% increase in cancer” or “Company Y discloses three unexplained deaths from patients in key trial.”

CVRs are generally tied to companies whose value comes from one or two key products; if one of those headlines / risks comes to pass and causes the deal to break, the stock is not going back to its pre-deal price. It’s going lower. Much lower. It’s going to be priced as a company facing massive legal risk whose key product is basically worthless. You’re probably looking at a company that goes from trading on a promising potential blockbuster drug / product to a company trading around liquidation value (with some legal liabilities factored into the liquidation!).

Now, to be fair, this risk is extremely low probability. These deals tend to complete in pretty short time frames (the majority of CVR deals I listed earlier are through tender offer mergers that take <2 months to complete), and the products and drugs at the heart of these deals generally went through extensive due diligence by a very sophisticated corporate buyer before the merger contract got signed. But low risk does not mean zero risk, and there’s a big difference between the two! These CVRs tend to price in ~99% implied probability of the deal going going through (or more if you believe my “the downside is way lower” thesis!); can you ever be 99% certain of something in the stock market? Paying 99% for anything tends to be a recipe for disaster, and remember: to get these CVRs to a size where they begin to approach mattering to a portfolio, you need to really size up the deals.

I walked through the math earlier that showed an investor would have needed to put >300% of their portfolio into ABMD before closing to get a 1% position in the CVR. Imagine doing that and waking up to news that the deal was delayed due to an investigation into some type of contamination linked to several of their products, and that JNJ was “considering options” to hold the deal until the investigation completed.

Yikes. I’m stressed just thinking about that scenario.

Again, the odds there are low. I’m sure one exists, but off the top of my head I can’t find an example of a deal with a CVR and a tender that blew up due to a product issue. Between the tight timing and due diligence done heading into the merger, those types of breaks are going to be rare / we’re truly talking edge case risk. But I’ll point you to a few historical examples that might suggest the path way to some risk here / that these are certainly <100% to close!

Fresenius / Akorn: Fresenius walked away from this deal after a whole bunch of issues came to light for Akorn, and Akorn would eventually file for bankruptcy. Somehow those issues escaped Fresenius during their initial due diligence; if the Akorn deal had been structured as a tender, why couldn’t Fresenius have missed them initially then found out about them during the tender?

Plenty of companies have bought medical companies and found themselves enmeshed in product liability issues a few years down the road. For example, Endo bought their women’s health division in 2011 and were so overwhelmed by product liability issues that they shut the business down by 2016. Yes, 5 years is a longer time than the 5 weeks needed to close a tender, but an unexpected legal liability absolutely could pop up!

This isn’t pharma, but consider the VVNT / NRG deal. It will have a happy ending as it seems likely to close tomorrow (March 10; I’m writing this March 9), but in February VVNT lost a massive court ruling that caused NRG to “evaluating the decision” and its options in regards to it. Yes, patent and legal risks are going to get diligenced in the M&A process, but I’d guess NRG way underestimated the legal risk at VVNT, and something similar can happen in a big pharma deal. The most likely way this would play out is a company announces a big multi-billion dollar merger, and the headline and valuation causes some company to come out of the woods and hit them with a suit that says, “Hey, turns out your product is violating our patent portfolio!” Maybe that suit is bullshit and quickly dismissed…. but we have seen companies with huge products run into unexpected patent issues and need to pay huge sums before!

Or, on the medtech side, Muddy Waters argued that Abbott missed a bunch of vulnerabilities in their purchase of St. Jude.

None of those scenarios are likely to play out. Again, tender offer deals falling apart are pretty rare given the buyer quality and tight timing…. but, given these are pricing at ~99% to close, it only takes one to blow up all of the profits from ever having tried this strategy (and that’s ignoring the risks of CVRs not paying out!).

Anyway, maybe I’m being too cautious on the risks associated with a CVR. As far as I can tell, no CVR deal has ever broken for non-regulatory / anti-trust reasons, so you could argue the solution to a lot of the risks I’m discussing is to wait till the absolute last second when every anti-trust / regulatory risk is settled to put on a CVR trade. That’s generally how I’ve tried to play these…. but, even with that patience, I’m always thinking about that enormous downside risk in a deal break, and it’s a risk most of the investors I talk to about CVRs don’t seem to have considered / thought through.

Odds and ends

Just to give a taste of how big the premiums in the CVR deals are / how big the downsides in a break would be, consider:

ALBO came at a >100% premium + CVR.

If you’re interested, you can see valuation of CVR on p. 31; projections on ~p. 26

CINC was at 121% premium + CVR

CNCE was a 33% premium plus a CVR

Three other attractive things about a CVR that are worth noting

Non-correlated: One nice thing about a CVR is they should payout regardless of what the stock market does. If your CVR is tied to FDA approval, the FDA is probably going to make the same decision no matter what the stock market does between today and whenever the decision date is. That non-correlation is pretty valuable!

Discount rate: You could probably argue there’s a little hidden value / margin of safety in the discount rate banks use for the CVRs. For example, if you read p. 35 of ABMD’s 14d9, you can see GS used ABMD’s WACC of 11.8% to value / discount the CVR. That WACC reflected ABMD’s cost of equity; once the deal closes, the CVR becomes an unsecured obligation of JNJ. Obviously the CVR milestones still need to be hit, but I would suggest the WACC of JNJ, one of the few remaining AAA issuers, is just a touch better than ABMD’s!

Synergies in a bigger company: CVRs are generally valued using the selling company’s standalone plans / projections. The selling company is generally sold to a larger company that should have a better sales force, legal team, etc, which on the margin probably improves both the sales outlook for the product and the likelihood of a FDA approval versus the standalone forecasts the company / banks use to fair value a CVR. Consider how JNJ talked about the ABMD acquisition: “J&J MedTech has an expansive global footprint, leading physician and education capabilities, commercial excellence and robust clinical expertise. These powerful assets will strengthen Abiomed's geographical reach and global therapy adoption to more quickly expand access to these technologies for the people who need it.”

This is deal specific to ABMD, but it’s worth noting that JNJ’s CEO is clearly focused on medtech M&A. On the ABMD deal call, an analyst noted, “J&J did a MedTech deal, I think you were pretty clear about your priorities when you assumed the CEO position.” That focus probably matters for ABMD’s CVR playing out; the CEO is likely to spend just a little more time / attention focused on growing ABMD’s business, and if the ABMD deal is not a success or he tries to play games around the CVR, he’s going to impact his reputation for future deals and open himself up to investor / activist criticism given good medtech deals is part of what he’s trying to sell himself on!

*I mentioned earlier that ABMD’s CVR was nontraded. A CVR can be traded, meaning after the deal closes the CVR will trade on the open market like a stock, or nontraded, which means that each shareholder gets a CVR at deal close and then is basically locked into the position until either the milestones get met and payments get made or the milestones get missed and the CVRs expire worthless. Traded CVRs have always been rare, but they’ve become increasingly rare recently. I’d guess the trend towards nontraded CVR continues for two reasons: there are much higher costs for administering a publicly traded CVR versus a nontraded CVR, and a nontraded CVR does not have the risk of a big activist stepping in, buying up a ton, and suing if some milestones get missed like a publicly traded CVR does.

It's spooky weird that you featured CVRs in this week's blog, I literally just posted some questions and analysis on a CVR deal that is expected to close imminently.

As a quick aside, your commentary on potential product issues reminds me of BAYRY's acquisition of CPTS and their Essure female sterilization device. I was covering healthcare at the time for a long/short hedge fund, and had talked to several docs about Essure. It was - or should have been - obvious to anyone with Internet access (there were reams of patient complaints and horror stories posted online) that Essure was highly problematic, Ess-entially a class action lawsuit in search of a California jury. I'm embarrassed that my recall isn't perfect (I've looked at literally tens of thousands of investment opportunities since then) but I think it's likely that "we" (aka "I") were short CPTS when the deal was announced. Clearly no one in BAYRY's legal department had Internet access; but then given BAYRY's corporate history, maybe they don't have a legal department?

I'm familiar with all the deals that you mentioned, and was lucky enough to own ALBO, CNCE, and HRZN when the acquisitions were announced, and bought ABMD for the CVRs. I've been pondering similar questions:

1. Is there any research on the returns from buying biotech/medtech CVRs?

It's tempting to speculate that - due to the structural issues that we have both identified - CVRs are the mythical Wall Street free lunch in the land were many professional investors would sell their grandmothers into slavery if they could get a fair price. But maybe CVRs are fools' gold, overvalued by risk-seeking lottery ticket punters and dewy-eyed biotech investors seduced by pie in the sky management projections? Natural selection would favor the latter, since legacy shareholders presumably owned the stock because they were hooked on the kool-aid. So maybe CVRs are a con perpetrated by cynical acquirers on gullible target shareholders ripe for manipulation?

It would be nice to have some data; and I'd be shocked if some academic hasn't crunched the numbers!

2. Who are the natural buyers of these CVRs?

I hadn't thought of the issues that you raised in terms of the personal incentives (or lack thereof) for arb analysts, but there are some other issues that do puzzle me. Presumably arb funds don't want to tie up capital that could otherwise immediately be leveraged and recycled into new deals? And presumably arbs' core competence is handicapping deal probabilities, not valuing and then warehousing esoteric CVRs (with all the associated administrative issues that you identified)? CVR investing also seems antithetical to the arb business model of highly-leveraged high-probability but very short-term outcomes?

3. As another of your readers observed, CVR investors who aren't playing the arb game can minimize deal risk by deferring purchase until deal closure is imminent. And as another reader asked, I'm also wondering if real time information is available on the expected closing date as closure is imminent? This is important, since as you note, you need to low a plot of capital into a deal to get a meaningful allocation of CVRs.

4. It's interesting to observe that the expected returns from CVR scalping are highly sensitive to tiny perturbations in the target's stock price., with the leverage proportional to the value ascribed to the CVR as part of the total consideration. So for example if you think the ABMD CVR is worth $2, your expected return is 100% at $381, but you can expect to lose more than half your money if ABMD's stock price pops 1% at closing.

CVR scalpers should therefore be very price sensitive and/or highly selective in finding deals where the CVR is egregiously underpriced and either the acquirer can't move the goal posts or there are material costs to doing so.

All of which suggests that the Wall Street free lunch remains as scarce as - but hopefully more tasty than - hen's teeth.

i agree that waiting until the last possible second to put on the trade is the best way to go about things here