Over the weekend, I put out a post (Weekend thoughts: interest rates and climbing the wall of worry) discussing where markets are right now and why I didn’t think a big increase in interest rates was a huge cause for concern for stocks.

I really enjoyed that post, and I hope you did too….. but it’s not where I originally meant to take the post! The post was originally meant to talk about the opportunity in banks right now / serve as a follow up to my “banks banks banks” post from earlier this year!

Long time readers / listeners will remember I got a bit obsessed with banks earlier this year on the heels of First Republic / Silicon Valley failing. I had three podcasts (that I can remember!) on the banks in the midst of the “crisis” (John Maxfield, Marc Rubinstein, and Sam Haskell) which I thought were all great; I also had several posts on banks (March’s “banks, cost accounting, and WAL” and a more bullish “banks banks banks” from May). I think all of those podcast / posts hold up reasonably well now, but if I had to sum it up my thoughts kind of went like this:

In March, when SIVB was blowing up, I thought banks were borderline uninvestable just because it was unclear how widespread the deposit flight could get.

In early May, I thought banks were really interesting. Banks had continued to sell off since March, and a wide swath of banks were trading at or below tangible book. Importantly, because banks had generally reported Q1 earnings by early May, banks were still selling off / panicking like there was going to be a deposit flight but we knew the deposit flight had generally been contained / limited to just the withdrawals around SIVB failing. That’s not to say another deposit flight couldn’t start again if things got really bad…. but the market was continuing to sell banks off like a run on the bank was in process, and the stats just didn’t really reflect that (most banks were starting to see deposits start to flow back in, while the market was treating them like they’d need to fire sell everything as every deposit left the system).

By early August, I was still interested in banks…. but with a ~20-30% bounce since the May lows, I thought banks were less interesting / you had to be much more selective to find value.

Benefit of hindsight, I should have just sold all my exposure then and moved on, but short term capital gains are wicked and the stocks still looked cheap….

Anyway, the banks have sold off pretty aggressively over the past ~month (alongside the whole market), and I think there’s a lot of value in them as they approach May lows. There are plenty of banks trading below tangible book value with good franchises, but the fun thing about buying banks below tangible book value is that you don’t need to be right on the “good franchises” part. A generic bank should trade for ~1x tangible book (or really a slight premium), so when you’re buying a bank below tangible book you’re really not underwriting much other than there being no huge hidden disasters on their balance sheet and management not doing anything stupid.

That was a little wordy. Back in May, right when the crisis was peaking, CFG’s CEO was at Barclays and framed the opportunity much more succinctly / in a way that stuck with me:

It looks like a screaming buying opportunity when you can buy these banks at tangible book or even below a little bit. Historically, you've made a killing. That should restore itself. You put in your notes about how the relative valuation to the S&P is kind of at an all-time low. If you go back 100 years, it's probably as low as it's ever been.

By the way, as you finish reading that quote, I’ll note that CFG currently trades for <$24/share with a tangible book that’s approaching $28/share despite consistently putting up ROEs in the low to mid teens. On top of that, they’re well capitalized and they return a decent amount of capital to shareholders (their dividend yield is >7%, and YTD through Q3 they’ve bought back >$900m of shares against a market cap that sits just over $11B right now.

Anyway, CFG’s just one example; there are plenty of others like it. All of them have plusses and minuses, but on the whole I’d guess a basket of them does very well over the next few years.

As with all things, you do want to do some work on what’s actually in the “book” part of book value, as I think there’s a lot of dispersion between banks and some small work / digging will let you find a lot of differentiation / high grade the opportunities. For example, Bank of America (BAC) trades for ~$26/share. Book value was ~$32.65/share at Q3’23, and tangible book was $23.79/share. They’re too big to fail (so you probably don’t need to worry about deposit flight) and their returns on tangible equity are ~15% (which would suggest the bank should trade for at least 1.5x tangible book, probably higher). Sounds like a buy, right?

Maybe! But if you look at their Q3’23 financial supplement, they have >$600B of held to maturity debt that’s sitting on their books at cost. They’ve lost $131B on that debt; marked to market, that would wipe ~$16.60/share off of BAC’s tangible book.

Now, you could argue that BAC is too big to fail, so they can clearly hold all of those assets to maturity, and that hitting them for the value of those HTM losses gives them no value for their deposit franchise. And there’s something to both of those arguments! But, just for fun, let’s compare BAC to COF. COF trades for ~$90/share, which is roughly where their tangible book was at the end of Q2’23 (they haven’t reported Q3 earnings yet; just given the karma odds of writing things online, I’m sure they’ll be a disaster just so this paragraph doesn’t age super well / the universe can spite me). So they’re a hair cheaper than BAC at ~1x tangible book…. but COF does not have any held to maturity securities. In fact, if you look at COF’s balance sheet, the book value of their loans for sale is slightly under their fair value, so you could argue book value slightly understates COF’s fair value.

The point I’m trying to drive home is this: if I showed you a basket of twenty banks trading around tangible book value, you might be tempted to just buy all of them as a basket. And that might be the right move…. but I’d point you to the COF / BAC example; while all the banks might look similar on headline numbers, I’d suggest COF (and banks like them without huge HTM marks) is way cheaper than BAC (and banks like them with huge HTM marks) just given the lack of huge held to maturity losses. Of course, mere cheapness does not mean COF (or any stock) is guaranteed to outperform. BAC and COF have substantially different assets (COF is much more consumer focused, so a weaker economy probably has much more effect on them), and BAC can benefit from flight to safety in serious distress thanks to basically being backed by the government.

Anyway, if I said “I think the banks are cheap, and a basket of them are likely to outperform” I’d guess I’d most frequently get three pieces of pushback:

Isn’t the looming commercial real estate crisis going to kill the banks?

Won’t the bank die if the economy rolls into recession and defaults rise?

Aren’t the banks going to get murdered by the increase in interest rates?

And those are all good pushbacks!

I’ll address them all individually, but before I do I’d make two general points.

You pay a high price for a cheery consensus…. Given most banks are trading around tangible book value, I’d suggest those pushbacks are all pretty baked into the stock prices

On points #1+#2, we’ve been hearing talk of looming commercial real estate issues and recession risk for ages. Remember, it was just over a year ago that 100% of economists suggested we would head into a recession in the next twelve months. Banks generally get killed when things suddenly go wrong; given how long we’ve been predicting recession / commercial real estate issues, all of the banks have had ample time to start building up reserves against their loans and increasing capital, so I’d be pretty surprised if we saw huge issues at banks from a garden variety recession or from commercial real estate if it stays on its current trajectory (of course, if the recession was a real whopper, or if commercial real estate took a massive turn down and spread through all sectors, all bets would be off!).

So let’s just quickly talk about each of those points of pushback.

Point #1 is commercial real estate. And I think the place to start here is with a clarification.

When I talk to investors, a lot of them seem to think that every bank’s balance sheet is loaded with loans to huge office buildings in Manhattan, Chicago, and San Francisco that are currently sitting empty and will default as soon as the loan comes due.

That’s really not the case; for the most part, the loans to the billion dollar office buildings are sitting at life insurance companies or in CMBS securities. Some of the largest banks certainly have some exposure, but it’s small in the grand scheme of their trillion dollar balance sheets and once you get away from the mega-cap banks most banks have limited office exposure overall and almost no exposure to the downtown skyscraper type office building.

For example, consider Western Alliance (WAL). I chose them because they were (and maybe still are) one of the banks in the epicenter of the post-SIVB crosshairs. The slides below are from their Q3’23 earnings (released just last week). To sum, 20% of their loans are to commercial real estate, and only 5% of their loans are to office buildings. Of those office loans, only ~3% are to CBD offices, and their whole CRE loan book generally is pretty conservatively underwritten (LTV in the 50-60% range, no mezz or junior debt below them, and only ~5% of their loans having LTV >80%).

Again, I’m not saying the commercial real estate couldn’t get worse, nor am I saying there won’t be a few banks with problems…. but, on the whole, I think the fears on commercial real estate are overblown. Most banks I look at look similar to WAL: low exposure to office, de minimis exposure to CBD office, and on the whole their portfolio is made at reasonable LTVs.

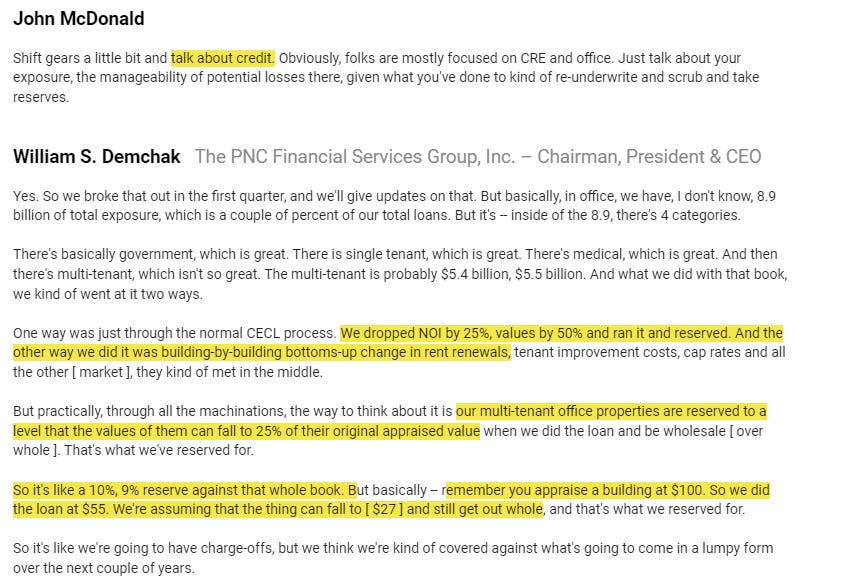

And remember: it’s not like a potential CRE crisis is coming out of no where! People have been talking about CRE having issues as interest rates rise for years, so banks have had a long time to adjust their portfolio and take adequate reserves. This is a bit dated, but PNC discussed how extreme they’d marked their office loan book at a conference earlier this year:

Remember, those marks are already on PNC’s books, so for them to book a loss from a “CRE crisis”, the losses would have to be in excess of the draconian scenario they laid out above (obviously that’s only on office, not their whole CRE portfolio!).

Speaking of marks and things possibly getting worse, let’s turn to point #2: won’t banks die if we go into recession and defaults rise?

To start, I’d just note: it’s not like banks have never seen a recession before. And remember: banks have had a long time to prepare for a recession; again, 100% of economists surveyed last year thought we’d be in a recession by now! That outlook has given banks plenty of time to prepare for a recession, and they’ve done that in a variety of ways.

Some have prepared for a recession by high grading their loan portfolio. For example, consider ALLY. Over the past two years, the share of loans they underwrite to their best borrowers (“S-Tier”) has gone from 24% to 37%, while the share to higher risk “B-Tier” borrowers has gone from 21% to 14%.

Others have prepared by building capital. For example, CMA turned off share repurchases early in 2022; by doing that, they’ve substantially built up their equity capital over the past year, and they’re now well in excess of their ~10% target.

Banks have also prepared with their loan loss reserves. It varies from bank to bank, but in general most banks have been underwriting loans and reserves with a recession in mind. Go look at the 10-K of any bank from earlier this year and look at the assumptions for credit losses; I guarantee you that the vast majority of banks you find were underwriting their portfolios like we were already in a recession. For example, to stick with CMA, here was their base case forecast for their credit losses from their 2022 10-k:

To summarize: they assumed we’d be in a recession in the first half of 2023, and they underwrote their portfolio on that! So their loan losses should already be incorporating any recession, and every quarter we don’t go into a recession let’s them build a little more capital (on top of their normal capital build from earnings).

Anyway, most banks have employed some combination of the three points above (high grading their portfolio, building capital, and underwriting / reserving to an imminent recession) over the past year, which should leave them very well prepared for if and when things do get rocky.

Does that mean the banks won’t take losses once a recession hits?

Of course not!

Has every bank been similarly prudent?

Again, of course not!

But, on the whole, the banks I’ve been looking at are overcapitalized and conservatively provisioned. We’ll have a recession one day, but unless the recession turns out to be a true killer, I’d expect most banks to pass that “recession test” with flying colors.

Finally, let’s turn to point #3: won’t the rise in interest rates kill banks?

I think people will ask that question and, depending on who asks it, have a different theory behind how rising interest rates kill the banks.

The first theory would be that the rise in interest rates knee caps the economy in some way, causes a wave of defaults, and destroys the bank’s loan book. That “economic destruction” scenario is somewhat addressed in points #1+#2 above, so I won’t really address it again, but obviously if you think the economy is about to implode (not a recession; a full implosion!) that’s a reason to be cautious banks (which are fundamentally levered plays on the economy!)…. but it’s also a reason to be cautious basically everything and probably start thinking about going long guns / ammo / canned foods as a hedge.

The second theory is that the rise in interest rates destroys banks’ earnings. And it’s that theory that’s kind of crazy to me.

The old rule of thumb is that banks borrow short to lend long. The absolute worst environment for them was the environment we saw in Q1 + Q2, when short term interest rates were substantially above long term interest rates (for example, in late May, the fed funds was 5.25% and the ten year was ~3.5%, so you’d get paid more in interest from parking cash in a money market than investing in something long term).

The recent rise in interest rates has seen short term rates remain stable while long term rates have shot up; as I write this, the 10 year is at ~4.9% while fed funds are 5.5%. That “ST rates higher than LT” inversion still isn’t ideal, but it’s actually much better for banks than the Q1/Q2 example I used above.

At their core, banks are interest rate sensitive creatures. Nothing about the SIVB / FRC blow ups have changed that. Deposit betas remain well below 1; most banks I’m seeing are in the 50-60% range (i.e. for every 1% move in interest rates, a bank needs to pay 50-60 bps more in interest on their deposits), and most bank loans are floating rate. That means as interest rates rise, the banks should be more profitable (for a 1% move up in interest rates, their main cost of funding (deposits) will have increased in costs by ~50 bps while their main source of earnings (loans outstanding) will have increased by 100 bps), and with the yield curve getting less inverted, cash sorting and deposit betas will likely stabilize lower, allowing bank earnings to really start to shine through.

Alright, this post has run long enough. To wrap it up, I think banks are pretty attractive right now. Will we hit a recession? Will we see more CRE issues? Who knows! Probably yes to both (I mean, on a long enough timeline of course, but I’d guess most people are asking those questions with a near term focus in mind), but across the board I’m seeing banks that are well capitalized and well reserved, and they’ve had well over a year to start preparing for issues. It’s generally sudden issues that kills banks, not things they’ve got line of sight to and can prepare for. If you can handle a little volatility (and are willing to dig a little under the hood to banks with more asset issues), I think a basket of banks will likely do very well over the next few years.

I think your COF/BAC comparison is interesting in a sort of "not everything that counts can be counted" way. The truth of this comparison is really somewhere in the middle of your conclusion. The fact is, in a perfect data world, loans on the balance sheet would be marked to market as well because interest rates increasing reduce the economic value of those assets. Just because accounting standards only adjust for tradeable assets doesn't mean BAC should be given a full discount for having more liquid investments. The real tangible book should be adjusting for all these investments at current discount rates.

I like FHN for many of the reasons discussed.