Let’s pretend you and I grabbed lunch yesterday. After you and I had exchanged initial pleasantries, you asked me what my favorite current investment was, and I spent the rest of the lunch talking up dominant tech company X. For our purposes, let’s call this theoretical company Megahard.

Now, Megahard is expensive on headline numbers (it trades for ~35x EPS, and it sports a market cap that would rival or even eclipse most European countries’ GDP), but it’s clearly one of the best businesses in the world. Among other things, Megahard is a play on AI and cloud computing, they’ve got an incredible SaaS revenue stream from products that are literally embedded into every business in the world, and their CEO and top management team are universally considered one of the best in the world (if not the best). You probably leave the lunch thinking Megahard is clearly a great business but wondering if you can really generate alpha investing in a company that large at that multiple.

A few years go by, and you and I schedule another lunch. We meet and talk about how it’s been way too long. You ignore that I’ve clearly been snacking a little too hard; I don’t comment on how quickly your hairline is receding. After catching up, the conversation turns (of course!) to our favorite stock ideas. Again, I pitch you Megahard. The stock has not done well since we last lunched; the AI play didn’t work, and the company is losing ground in cloud computing. Perhaps things stopped working because the genius CEO left about a year ago, and he was replaced by his top sales guy. It’s early, and while the top sales guy clearly loves the company and is crazy enthusiastic, I’m not convinced he’s got what it takes when it comes to operations, strategy, or capital allocation. Still, the company is just way too cheap; its multiple has been cut in half, and it’s still growing nicely. It trades in line with the market multiple for what I consider to be a collection of some really good business, though maybe they aren’t quite the best businesses in the world and there are some terminal value questions for a few of their businesses. You leave the lunch feeling bad for me; I took a huge stake in Megahard, the position has gone against me, the story has materially worsened, and I clearly can’t admit I’m wrong and move on.

A few more years go by, and we finally get another lunch on the books. Your hairline is a thing of the past, but you’ve admitted it and gone with the clean shave. Good for you; you look great! I, on the other hand, am a disaster; my nightly habit of eating a pint of Ben and Jerry’s has caught up to me. We exchange pleasantries, and just when the conversation is about to turn to stocks you ask me, “Hey, are you still holding that dog Megahard?” You see, at this point, Megahard is the butt of every joke in the financial world. The CEO is widely acknowledged as a disaster; he’s made multiple acquisitions that combine an incredible willingness to overpay with the strategic rationale of a toddler who skipped their nap and had an extra juice box. The cloud computing division is dead, and, while most of Megahard’s other products are still putting up some growth, they are facing serious terminal value questions as the world changes around them and they refuse to keep up. Despite the wave of negative news, I am undeterred! “Of course I still love Megahard. Yes, cloud computing is dead, but the stock is sooooo cheap. It’s trading at just 10x earnings, and it’s even cheaper when you back out the cash! The market is way overpenalizing them for how bad the CEO is; he can’t last much longer!”

You leave feeling sorry for me (and also glad that you gave up sugar a few years back!). I was clearly wrong on Megahard originally, but I’ve let thesis creep drift in and I’ve been unable to admit my error.

As an investor, thesis creep is one of the most deadly sins. It’s one thing to lose money, but where you really hurt yourself is when you delude yourself about a position and keep changing the story to justify holding it / not ripping the band aid and realizing your loss. When that thesis creep drifts in, you tend to have huge blind spots to rising risks, and you can easily end up with a position that goes down for multiple years in a row (creating not just losses but huge opportunity costs as the rest of the market is likely rising). The Megahard example is perhaps the worst case of thesis drift I can imagine: I went in buying a world beating company at a lofty multiple, and I held it all the way through as the business faltered because the multiple kept getting cheaper and cheaper. I got hit with the double whammy of a declining multiple (the multiple likely dropped ~75%) and declining earnings. Ouch!

Astute readers might note Megahard bears an awful lot in common with Microsoft. And that, of course, is intentional; Megahard is a near perfect mirror to Microsoft over the past ten years. In fact, I created Megahard to be Microsoft if you “Benjamin Button’d” them; instead of starting with a company that was really cheap and had questionable terminal value and an awful CEO and growing it into a world beater; you started with a world beater and ended with an awful CEO and questionable terminal value.

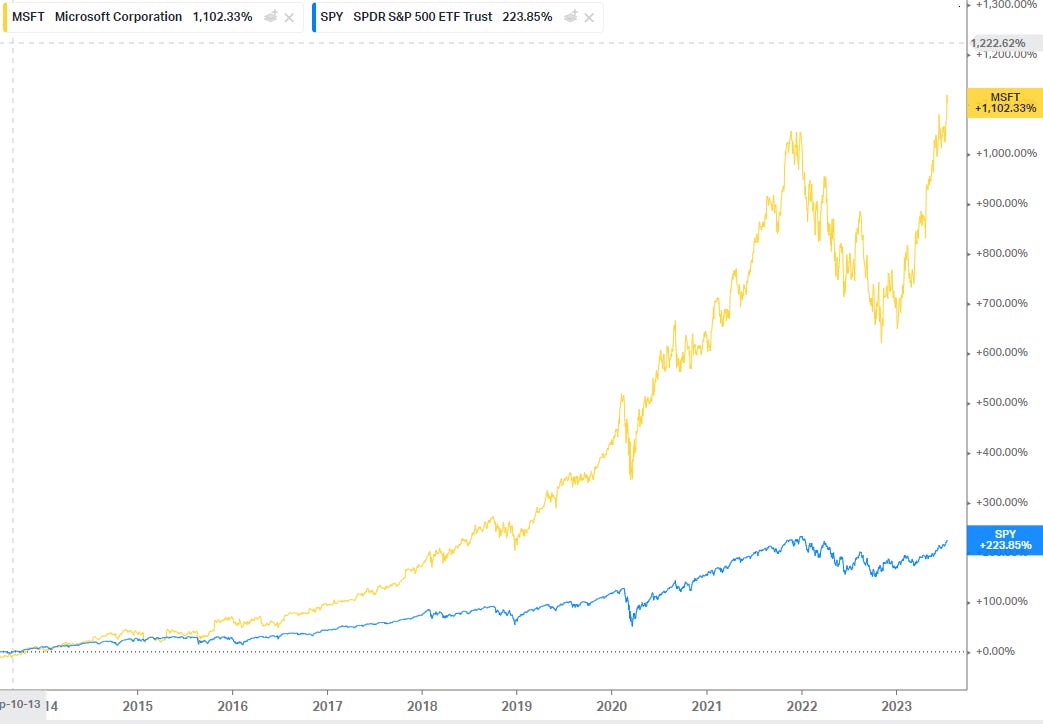

Long time readers will know / remember that I’m a little obsessed with the “Microsoft from ten years ago” story. And with good reason! Microsoft has delivered unbelievable returns over the past ten years, and it was there sitting out in the open. It had some of the best talent and business franchises in the world, and it was trading for <10x earnings with ~20% of their balance sheet in cash. Plenty of value investors saw that combo, took a huge swing, and have built an impressive track record in large part thanks to that one impressive bet (something similar could likely be said of investors who bought AAPL at ~10x P/E in ~2015).

But here’s my question: if I would have had thesis drift when I bag held Megahard for years as the business declined, why is an investor who bought Microsoft ten years ago lauded? Is this process really repeatable? 10 years ago, you were buying Microsoft saying “I bet they don’t die quite as quickly as the market is forecasting.” No one was thinking about AI or cloud computing. Heck, ten years ago Microsoft’s track record of getting into new businesses / ventures was so poor that if they had announced they were getting into the AI game, you would have begged them to just take the money and go put it on red at a roulette wheel because the NPV of literal casino gambling would have been better than Microsoft investing in a new venture.

Investing is a returns driven game, so perhaps the answer to “why are they lauded” is simply “scoreboard.”

But I remember 2022 very well (it was, after all, only ~7 months ago!). I’m sure I’m not alone in having several stocks that I bought cheaply / well in 2020 that soared in 2021. At the beginning of 2022, I looked at a lot of them and thought “well, they’re pretty fully valued….. but these are good businesses, and they’ve got lots of new adjacent markets they can invest in that can drive growth / create a bunch of additional value! Why take the tax hit when I can compound as they capture new markets?”

In general, those stocks got killed in 2022.

Some of them have recovered a lot of that value loss this year. Some of them will probably recover the value loss over the next few years. But many of them will never recover to the highs they hit in early 2022, and I can promise that none of those companies are the next Microsoft.

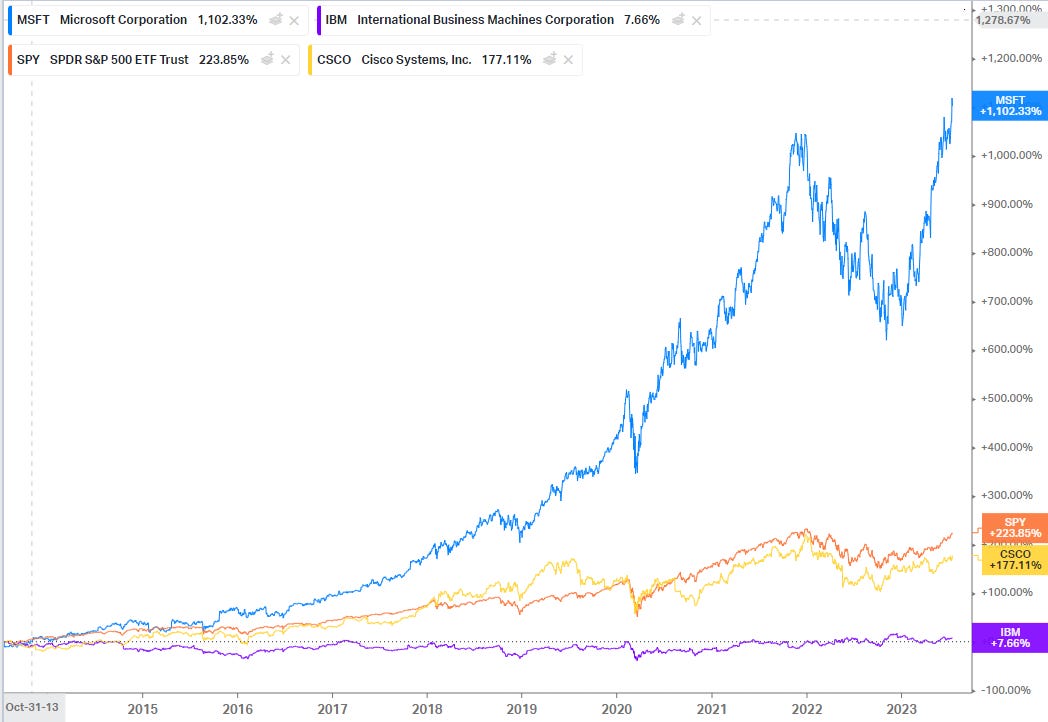

We laud investors who’ve held Microsoft or some other compounder for the past decade. And perhaps rightly so! But for every Microsoft that has compounded from deep-ish value to a full on compounder, there’s another deep value stock that’s failed to takeoff. Rewind 10 years. IBM and CSCO both traded for roughly the same multiple as them. If you had asked most investors, I think they would have told you that CSCO and IBM were better run than MSFT. IBM had Buffett as an investor, and both CSCO / MSFT probably had less perceived terminal value risk than Microsoft.

Both CSCO and IBM underperformed the indices (and dramatically underperformed MSFT). We laud MSFT investors today because of those huge returns, but how much better are those investors than investors who chose CSCO or IBM 10 years ago? The thesis was very similar between all three.

And was an MSFT investor in 2012 better because they chose MSFT over the other two then, or were they better because they held on to MSFT in 2017 when their original thesis had already fully played out and they were probably tempted to sell it?

Were they good investors for holding MSFT in 2017? What about the skill set of buying MSFT cheaply in 2012 suggests they were the ones who could successfully analyze MSFT’s competitive position in 2017? Did they simply get lucky that MSFT is a unique company, and they would have fallen into the same “hold in 2021, get crushed in 2022” trap I mentioned above with any number of other seemingly could businesses poised to take over new markets?

Are they good investors for holding MSFT today? Or have they simply been trained that MSFT is the GOAT and they should hold it forever? When will they sell? Investing can’t be as easy as buying the largest tech companies in the world and outperforming every index forever, right?

Anyway, I don’t know the answer to any of these questions. And I certainly don’t mean to pick on Microsoft or anyone who has held it for the past ten years. Again, investing is ultimately a results driven game, so if you have held MSFT for 10 years you don’t have to take crap from anyone. You can just point to the scoreboard and drop the mic while you sail off to your private island.

But I really liked that Benjamin Button story of reversing one of the most popular investing stories out there and showing how concerning that fact pattern would have been if it hadn’t worked out so successfully, and I wanted to share it with you because it’s been on my mind.

I just joined ..Ive been an investor in the TMT space for 25 years.. neve hit the ultimate grand slam ... but I did ok...

Whats the next MSFT AAPL etc .. that u feel worthy of investing near and long term with scale and TAM mgmt etc?

https://static.fmgsuite.com/media/documents/db64b928-53d6-43a9-a4d0-a9d2f69f76ba.pdf

Christopher tells in the pages 31 to 41 the history of Robert Brookings Smith. He was a stock broker who in 1932 bought GE stock as a net net, for half the cash and working capital. The stock would cagr 40% over the next 5 years. But he didn't sell. As the Jack Welsh years were coming to an end, over 1998 he donated the GE stock to family foundations and other charitables, that promptly sold the stock. I can't think a greater thesis creep than GE stock over the 20th century. He hold throught all of that and then sold at a secular peak. Is he good or he just got lucky?

I think it's worthwhile to extend the timeframes. The day will come where Microsoft is a sell and you'll know who is a Brookings Smith and who just got lucky. Similar to GE, Microsoft is a tough company to run. Microsoft had a greater market cap than most countries in the past and nonetheless it traded at 10x earnings after 35 years in public markets.

In reality, most people didn't hold though it. They sold because the thesis had changed. Other people bought because some new thesis. I am selling a bit here because the thesis seems complete.

On the other hand, picking companies like MSFT, makes you suscetible to have the tailwinds of thesis creep. There's significant auto-correlation. Success begets success. This will never present to people buying stock for 60 pennies in the dollar. So I think investors deserve some credit for choosing a company that is vulnerable to thesis creep.