Caligan Partners' Dave Johnson on MorphoSys' $MOR change from royalty play to traditional biotech (podcast #173)

Dave Johnson, Managing Partner at Caligan Partners, makes his second appearance to discuss his thesis on MorphoSys AG (FSE: MOR; NASDAQ: MOR), including: history of the company, change in business strategy from a royalty play to traditional biotech, Pelabresib clinical trials for Myelofibrosis indication and more!

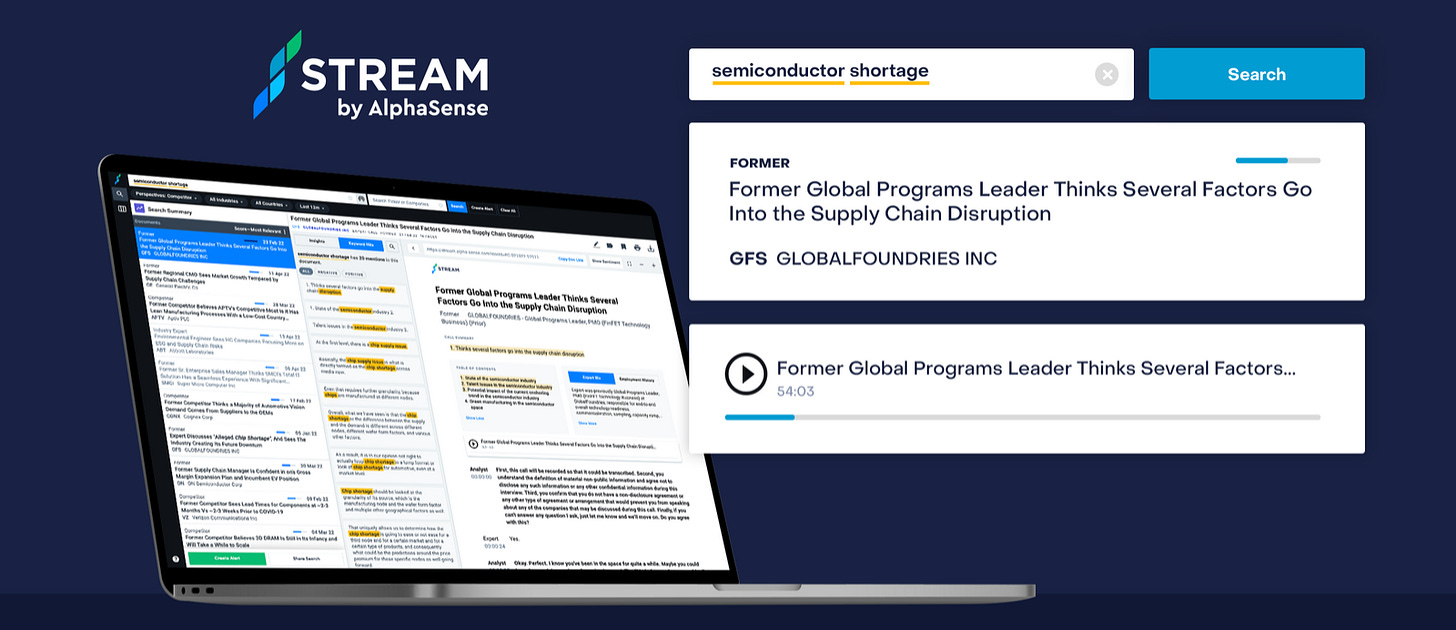

***This podcast is brought to you by Stream by AlphaSense.***

Expert calls just got easier.

Say goodbye to traditional expert networks with Stream by AlphaSense. Stream enables you to access high-quality expert insights, in less time and at lower cost. With proprietary search technology and a library of more than 30,000 expert call transcripts, Stream provides the tools to help you make smarter decisions faster. Sign up today.

Please follow the podcast on Spotify, iTunes, or most other podcast players, as well as on YouTube if you prefer video! And please be sure to rate / review the podcast if you enjoy it, or share it with someone else who would enjoy it (more listeners is a critical part of the flywheel that keeps this Substack and podcast going!).

Disclaimer: Nothing on this podcast or on this blog is investing or financial advice; please see our full disclaimer here. The transcript below is from a third party transcription service; it’s entirely possible there are some errors in the transcript

Transcript begins below

Andrew Walker: Hello. Welcome to Yet Another Value Podcast. I'm your host, Andrew Walker. If you like this podcast, it would mean a lot if you could rate, subscribe, review it wherever you're watching or listening to it.

With me today, I'm happy to have on for the second time, Dave Johnson from Caligan. Dave, how's it going?

Dave Johnson: Hey, Andrew. How are you doing? Thanks again for having us. We really appreciate it.

Andrew: I'm really excited to have you guys on. Let me start this podcast quickly with a quick disclaimer to remind everyone on this podcast that nothing on this podcast is investing advice. Please consult your own advisor.

That always applies, but probably particularly true today because, A, we're going to talk, at least, one stock - maybe a couple of stocks - in the pharma sector. The pharma sector is famous for your drug gets approved, it goes to a hundred; your drug gets rejected, it goes to zero. Hopefully, none of that happens here but obviously, just extra risk.

Then we're going to focus mainly on a stock that trades in the US, but it's European-listed for the most part. People should be aware foreign stocks carry extra risk.

But all that out of the way, Dave, this company we want to talk about is MorphoSys. The ticker is MOR. It trades in Germany. You guys have done a ton of work on it. You guys had a great presentation last week that I really cribbed for the majority of my background on this. But I'll just turn it over to you. What is MorphoSys? Why is it so interesting?

Dave: It's a really interesting company. I think it really gets to the heart of- you have very different investor bases in Europe and in the United States. In the United States, you've got investors in biotechnology stocks that the risk profile, the pipeline products that know the binary nature of a lot of these molecules, as you said, and the European investor base which is I would say a little bit more risk averse and would like the diversity of different shots on goal, a little bit more late stage, a little bit more fee for service.

MorphoSys started out as a German company that was focused on antibody discovery. If you're a large pharma company and you'd say, "I've got this target. I want to go see a library of antibodies that this company MorphoSys can develop that can maybe have a higher binding affinity than anything in my pipeline," you'd say, "MorphoSys, can you go find something that works for us for this target?"

MorphoSys would go do that. They would usually do that for a fee of some sort of nominal amount up front and a royalty on the backend. If you rewind to 2017, MorphoSys has twenty-eight partnered programs with fourteen different pharma companies, basically, all antibodies, all biologics. They had this really diversified way to play effectively innovation in biopharma where you had twenty-eight different shots on goal. You had a royalty on each of them if they worked. Investors loved it. European investors, in particular, loved it.

As part of their evolution along the way, they said, "Hey, we're pretty good at this antibody discovery. Maybe we should consider bringing one of our own along the way. If it's just 1 piece of a much larger pie that we don't have a lot of risk on, our investors would be okay with it." They did.

One of the things that was in their pipeline was anti-CD19 antibody which eventually becomes Monjuvi. This is the approved product that they have for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma which is the largest case of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma cancer out there. In 2020, they partnered with Incyte where they effectively agreed to both promote the drug in the US and Incyte take the drug ex-US. For that, Incyte paid them $750 million upfront. They gave them $1 billion dollars of milestones. Pretty good deal.

The other thing I should say is one of those twenty-eight programs from 2017 becomes J&J'S drug for psoriasis called Tremfya. MorphoSys owned a 6% royalty on a drug that, last year, did two-point-six billion. I would say analysts’ consensus is somewhere around four billion. Huge amount of money coming to MorphoSys. If you look at January 2020, MorphoSys was flush, cash-rich, huge portfolio. They just had a product approved. Things are going great. Stocks, probably, if I'm looking at EUR140 a share. But things didn't go so well.

Listen. Monjuvi is a great drug, the drug that they got approved; they got partnered with Incyte. It gets approved in August 2020. Listen. What happened with B-cell lymphoma is the space got a lot more competitive. When Monjuvi was approved, it was the first second-line agent. After your standard chemotherapy, patients become refractory. If they can't take a stem cell transplant, they need something else. It was the first second-line agent to get approved - I'm going to date myself - definitely, at least, a decade and perhaps potentially longer.

What's happened in the B-cell lymphoma space is that since Monjuvi was approved, 5 additional therapies have been approved including CAR T. What looked like open spaces where they were going to have a ton of patients coming on this drug has become a knife fight in the third line. Because they exhaust your CD19, they want to put CAR T before you. It has the same target. It becomes a knife fight.

August 2020, it launches. By that point, the market's already starting to see this is not going to be a billion-dollar-drug blockbuster. It's going to be a resource-intensive and much more modest launch. Investors started to see that. They started to rotate out of the stock.

But what really probably put the European investor base over the edge is in July 2021, MorphoSys says they took all of their royalty portfolios, all of these twenty-eight programs I told you about including J&J's awesome blockbuster drug they've got. They sell it all to a company called Royalty Pharma which I'm sure some of your listeners and you are familiar with. They sell it all for $1.4 billion upfront. Pretty good. Good package. They take all that cash. They buy a US biotech called Constellation Pharma with 2 assets in development and a whole bunch of preclinical stuff.

European investors, European analysts, and everybody said, "You've turned this really diversified antibody company into a US-style biotech where you have a commercial product and a pipeline asset." People just hated it. They saw massive rotation in their investor base. I think it was sixteen of the top twenty shareholders as of the beginning of 2020 all left, all left, 100% gone.

Andrew: It makes sense. As you said, you're here for royalties. Then the management says, "Hey, we were managing a stream of royalties. Now, we're going out. We're huge biotech players." It's a very big switch.

Dave: It's a very big switch, a little bit of a bait-and-switch, totally, totally. You fast forward to the company today. They've got Monjuvi which consensus is about ninety million bucks of revenue this year. It is marginally profitable in the US if you exclude the research and development costs, now, which Incyte picked up 55% of where they're trying to move it into follicular lymphoma and into first line B-cell lymphoma.

Then they have this asset called Pelabresib which is BET inhibitor in development for myelofibrosis which is the disease of the bone marrow where you have this malignant bone marrow that produces a bunch of bad blood cells, bad platelets. Your body can't handle it. Eventually, you're not producing enough of good red blood cells and good platelets. You become highly anemic. It causes a whole lot of comorbidities. You eventually expire.

What MorphoSys is today is one approved product that's a good product. It definitely fills an unmet need, really safe, really great for older and frail patients that can't take a stem cell transplant. Then they have what we think is an incredibly exciting shot on goal, a phase 3 in Pelabresib that you're going to turn over the data card in December this year, December 2023.

Andrew: I want to talk about how you guys got involved and got constructivist. I was flipping through their annual meeting deck which happened maybe 2 weeks ago I think. One of the calls is Caligan, 3%-plus shareholder. They talked a little bit about engagement [?].

I want to get there. But before, I think it might just help to frame this by talking. You've already mentioned their parts. Their parts these days are they have net cash, Minjuvi, Monjuvi, the milestones, and then the drug.

But the stock - again, not an investing advice - as we're talking, trades for about EUR27 over in Germany. I think it might help people to frame why you got involved, how you got involved as we started thinking about that. If we just quickly did where you see the value, the classic, some of the parts here.

Dave: That's super helpful. I think everybody is going to talk about there's a lot of negative enterprise value companies. There has been, in the biotech space, over the last 2 years.

Starting in December last year, MorphoSys was one of those companies. It had about EUR1 billion of cash. They had about six hundred-ish net debt. It was a very very timing market gap, effectively trading for nothing despite the fact that they had this approved asset in the US, an approved asset in Europe, and a late-stage phase 3 asset in development with Pelabresib.

We looked at it and said, "Okay. You got the net cash. It's going to cost you. You're going to burn some of that cash to get to this data card for Pelabresib at the end of 2023. But if you account for that, you still have a net cash position at the end of this year." This company still has positive cash flow per share at the end of this year.

What we said with Monjuvi was, "Okay. This asset's doing $90 million of revenue today. It's going to grow. You can always take a little bit of price. It's penetration and the community setting is still under-penetrated to where it probably is going to get to."

One thing that was really important to us is that they have to report a separate P&L for Monjuvi in the US, because they share it with Incyte. They both put the cost in. Then at the end of the day, they split whatever the profit is. If you look at 4Q 2022, they had taken an asset that was losing $20 million a quarter when it started to launch. They'd massively reset the expense structure such that it was profitable.

When we said, "Hey, if you run out the cash loads for this without assuming massive growth, you can have a positive NPV per share for MorphoSys shareholders on this asset."

Then in Minjuvi, which is the name of the drug in Europe that Incyte markets, they owe a royalty back to MorphoSys. That's the cash flow stream. There are sixteen analysts that cover Incyte. They all provide projections on Minjuvi. You have a reasonable degree of confidence about what that drug's going to do. Importantly, in Europe, CAR T is not as widely available. It's less competitive. Minjuvi actually sits earlier in the treatment paradigm where you're getting a healthier patient population. I bet you, if I was the betting man - I am I guess - Minjuvi is probably likely to be a higher peak sales than Monjuvi in the US excluding the first line of follicular dynamic which we can talk about later.

The fourth piece that we said - because we have cash, Monjuvi, Minjuvi, royalties, and then these milestones - one of the things we mentioned was when Incyte did the deal with them in January 2020, you had this package of milestones that is not sales-based. It's all regulatory-based. If the drug can get approved in these 2 indications that they're leading it in, which are follicular lymphoma and first line B-cell lymphoma, Incyte owes them up to $535 million straight. It doesn't matter if the drug sells zero or if the drug sells a billion. It is what it is. It's just regulatory-driven milestone. And Incyte is paying 55% of the cost.

We ascribe some probability of success to that to get to where we thought a base case value. If we put zero value to Pelabresib, which I think is completely unfair, what's our floor value for MorphoSys? That's really where the building block is. When we started getting involved, we said, "Hey, you own this option on a phase 3. Irrespective of what you think about it, you own this option for nothing."

Then as we started digging in, we got very excited that we think that they have a potential first-line drug in myelofibrosis with blockbuster potential that in December, in January, you will get them for free. You're paying a little bit for it now. But I would still argue that you're still getting it a very- you don't ascribe a high probability of success. But I think it's going to be a high probability shot on goal for this thing.

Andrew: I just skipped ahead. I'm cheating, because I'm looking at some of the stuff you guys have put out on this. But the stock today is twenty-seven.

I think the way you guys think about that is at the current price, more than half of that value would be covered by the net cash at the end of this year, so after two hundred million plus of cash burned for the remainder of this year. More than half the share price is covered by that plus Monjuvi, Minjuvi, and the milestones. You're paying for less than $13 per share net. You're getting Pelabresib which I think you guys think, risk adjusted, could be worth as much as $45 per share. Is that kind of how it is?

Dave: Yes. kind of up/down, exactly. We are going to always look for things that's three to one up/down. Right. You're paying 13 for something that we think is worth 45. That's [crosstalk].

Andrew: Risk-adjusted, obviously.

Dave: Risk-adjusted [crosstalk].

Andrew: It's worth it.

Dave: It's even more.

Andrew: I want to talk about Pelabresib [inaudible], because as people just heard, that's where the majority of the value comes. But I do want to talk about it, because again, the company has acknowledged it. You guys have talked about how you came to get involved in this, how you guys engage with the company, because, A, it's interesting and, B, I think how the company responds. You mentioned it was the best interaction you guys have had with the company whom you've engaged with. I think it's worth talking about that before we dive into Pelabresib.

Dave: Of course. We're always happy to talk about it. One of the things that we pitch about ourselves is we have active engagement in life sciences. That's the exposure we give to our investors. What does that mean? A lot of times - and obviously - people have seen that we've had some more hostile engagements. Sometimes we've had some really friendly engagements where we put pipes into companies.

But we have a very formulaic way. We sit down with companies. The presentation has 3 sections: Have you underperformed? Here are our reasons why Caligan thinks you underperformed. Here's what you can do.

When we sat down with Jean-Paul, who's the CEO here, we went through section A, section B, and we came to section C. We said, "Hey, the underperformance was clear." The reason why we thought they had underperformed was, obviously, we thought the Monjuvi was potentially negative NPV and that they should try to get out of it. We were wrong. But that was one of our [inaudible]. We thought that they had a convertible note that was creating an overhang on them, that they were trading at a big discount that could be attractive. We thought that the market was giving them credit for their early-stage R&D. Of course, we said, "Hey, you're a US biotech in a German shell. You're in no man's land between an investor base that's going to appreciate what you are and an investor base that has no idea how to value you."

When we got to section 4 about how to do things, Jean-Paul was like, "Agree. Disagree. Agree. Agree." Then he went through with an incredibly detailed rationale, all based on public information about, "Here's what you said on Monjuvi. You're missing the milestones. This five hundred thirty-five million, we have a high chance of getting this. We believe in these programs. Incyte's bearing 55% of the cost of those. All the money's in the ground. It's kind of sunk. You're going to turn over those data cards pretty soon. That's worth a lot of money to us. It's worth more than our market cap."

He's right. On the convert, we sat down. We said, "Hey, you're trading a big discount. You get a big cash balance. You can capture some of that discount. It's a low-risk way for you to get value to your shareholders."

Six weeks later, they announced that they're tendering for their convert. They bought back 25% of it at a better price than we thought they could have gotten. It was super great. A couple of days later, after we met them, they'd cut all the early-stage R&D. They basically said, "We are going to focus all of our resources on our mid to late-stage pipeline."

On the US thing, they said, "Listen. There are some things that you can't appreciate about tax consequences for moving from one jurisdiction to another. We've got a really great German heritage. But we hear you on that we are a little bit different than what a normal German-listed company is."

It's been a fantastic dialogue with us. One of the things that we will always appreciate is our operating partner with us in this investment is Paul Fontaine, a Belgian national. He's had a lot of experience brokering between Germans and French. He's been there with us the whole time.

I think we've had a great engagement with Jean-Paul. We think he's doing all the right things. He might have been doing all these things without us ever showing up and doing the presentation A, B, C. But that's great. When that happens, that's fantastic. That's perfect alignment. We got value in the investment. We've got a management team that's doing the right things. That's great. We're excited about that. It's a lot less work than the other stuff.

Andrew: It's a lot less work than running a proxy fight and having to yell at them and worried about getting the lawyers involved. I absolutely hear that.

Let's turn to where you guys think - as people heard from some of the parts - the majority of the value here is, the potential to be worth more than the entire market cap, and that's Pelabresib. I guess do you just want to talk what is Pelabresib? I have some questions here. But why don't you just walk us through what Pelabresib is and why you guys are so excited about it?

Dave: Let's take a big step back and talk about the disease a little bit first. Myelofibrosis, let's try to reduce it to really basic. Your bone marrow becomes malignant. You produce a lot of cells. You produce a lot of cells that are not helpful to the body. Blood is deformed. Malignant cells are in your body. Your body compensates.

One of the ways that it compensates is your spleen, which is another place in your body where cells are made, begins to overcompensate. It effectively tries to make more platelets. It tries to make healthy red blood cells. It tries to process all the bad blood cells your bone marrow is making. This is where the cytosis comes in. They're trying to kill them all. They try to get them out of your body. The spleen basically starts to work overtime.

The spleen is right here. So you see these patients. The biggest thing that they present with is splenomegaly where their spleen is enlarged massively. You'll see a person. They've got a huge perfusion of what looks like their stomach on the side of their spleen. It's just enlarged to a massive volume.

Andrew: If people are watching YouTube, they can see me. I keep looking right, because you've got the photo in your deck. You can tell there's something going on there. It's a man. It looks like he's almost pregnant. His stomach is... it's not bearable.

Dave: Terrible. Terrible. The thing that you see is that these patients don't have enough red blood cells. They become anemic. They become fatigued very quickly. They've got fibrotic activity in their bone marrow which is a kind of permanent scarring. Eventually, they're not going to produce enough healthy cells to sustain their life.

The other thing that happens is because the spleen enlarges, it starts pushing against the stomach. Your stomach starts to shrink. You feel like they're full more quickly. Despite the fact they're spleen [inaudible], it looks like they're completely enlarged. You could look like you're pregnant. You start to lose a lot of weight.

Andrew: The person in it looks quite emaciated.

Dave: It's a terrible disease like a hybrid...

Andrew: This is eighteen thousand patients in the US you have. Most of these rare diseases, unfortunately, are awful. Every time I look at one of these, I'm always just like, "Oh, my God. I'm so glad I don't have it." It's terrible. You feel awful that this happens.

Dave: That it happens. It generally presents in the early 60s. If it presents, a high-risk patient - somebody who's got other comorbidities - you're probably looking at a year and a half of life expectancy. For some of the younger patients that have it - because it's always a spectrum - if you can manage it and you can tolerate some of the treatment, you can get up to 5-ish years.

But it's a terminal disease. It's not curative. You’re not able to stop it. Nothing's been able to show to date that you can stop and have anti-fibrotic activity in the bone marrow that can reverse what's happening which is you have got bone marrow producing bad cells.

The way that this disease is treated today is with a JAK inhibitor called Jakafi from Incyte. What Jakafi does as a monotherapy- you or I come in as a newly diagnosed patient. We've got a big spleen volume. We've got all these symptoms of fatigue. We're tired. We're anemic. We've got a really screwed up blood. Sometimes we have thrombosis, because we don't have enough platelets that are knocked down.

You come in. What do they do? They give you this Jakafi. They say, "What's it going to do? Well, in 40% of patients, it's going to shrink your spleen volume by about 35% in about twenty-four weeks. Forty-five, forty, somewhere in that range. If you have a baseline symptom score of this fatigue, anemia, headaches, all that stuff, in about 40% of those patients, it's going to take it down by about half in the twenty-four-week period."

It helps. It's a good drug. It helps. Most of the patients stay anemic. Some of the patients have thrombocytopenia. It does knock down your platelet count a little bit more. It does require a lot of dose reductions, because people can't tolerate the higher dose which is obviously you're going to get a better therapeutic window at that higher dose, and they got to go down to a more suboptimal dose.

But it's a good treatment. It's a good drug. It's frontline. This year, across a different number of myeloproliferative neoplasms, majority of which is myelofibrosis, it does about 2 billion dollars to 4 in that range, US and then there's European partners.

Sorry. Just to go back on the disease, that's the treatment. All the drugs that are being tested in myelofibrosis are all add-ons to this drug Jakafi. What they're all trying to do is to try to do what Jakafi does better. Help Jakafi. You want synergistic activity between the 2 molecules, because it's important. No matter what, because it's an approved standard of care, patients are going to get put on Jakafi immediately when they get diagnosed. All you can do is try to do better than what Jakafi does alone.

What did Pelabresib do? Pelabresib is a BET inhibitor. The BET proteins are implicated in a lot of the fibrotic activity associated with myelofibrosis. It blocks that BET pathway. It allows the body to better control this abnormal cell production and to basically relieve these symptoms of anemia and thrombocytopenia.

In a large phase 2, about eighty-four patients, they gave Pelabresib plus Jakafi to newly diagnosed patients. What it showed was instead of that 40% that Jakafi does alone, 68% of them got their spleen volume shrunk by 35% in twenty-four weeks. Almost a third more patients got a better response on spleen volume than just with Jakafi alone. On a symptom score, instead of that 40% of patients getting that symptom score down in half, it had about 56%. So meaningful improvement on the efficacy side.

But then when you do these combination trials, how much toxicity you're adding by giving them another drug? The answer was basically not many. When you look at the anemia, it was actually better. The patients became less anemic than they are on Jakafi alone. For the thrombocytopenia, which is your platelet level, it didn't have any effect. That's one of the things that's limited that inhibition development for a big pharma previously.

Andrew: If I could just add there, look. Improved efficacy and no increased toxicity, that's great. But the 2 things I wanted to add there - I'm stealing this from you; I'm looking at your slides - number 1, yes, improved efficacy is great. But the most important thing is that, to me, the lower bound of the confidence interval on it is actually higher. If the other drug, the 40%, the lower bound of this confidence interval - I think was 57% - is higher than that, it's not just that it was a little higher. It's not that, "Hey, this was a little bit of luck, 1 or 2 patients." There's a confidence interval here. Statistically, you're well over the improving efficacy even at the lower bound of that confidence interval. I don't know if you want to add anything there.

Dave: You said it better than I did.

Andrew: The other thing - this might be jumping a little bit ahead - is the stock has gone up a good bit over the past couple of weeks. I was talking to someone on your team. I was like, "Oh, man. Wish we had talked about this 2 weeks ago when it was a little lower." He was like, "Yes. Obviously, you'd love to get in as low as humanly possible. That's nice," again, you can tell me if I'm putting words in you or your team says, "But we're more positive. We think the market is actually under-appreciating that they've really enrolled the next trial for Pelabresib really quickly," I'm a generalist, "We think generalists don't understand that when you enroll in a trial this quickly, it's because doctors, the company, everyone is seeing really great results. They really want to get their patients in there."

Again, I don't want to put any words into your mouth. But if you just want to talk about the dynamics of the trial.

Dave: When MorphoSys acquired Constellation, where Pelabresib came from, in July 2021, Constellation was originally going to try to enroll three hundred patients. They launched that, I want to say, at the end of 2020, November-ish. At the same time, you had AbbVie who's running another compound called Navitoclax in combination with Jakafi. They said they started their trial in September 2020. They said, "We're going to roll two hundred fifty patients."

What MorphoSys did when they acquired Constellation - going back to your point about confidence intervals - they said, "We don't want to take any risks. We're going to increase our enrollment from three hundred to four hundred patients to make sure that we have the highest degree of success in that symptom score reduction. We really make sure we overpower this study to make sure we eliminate that left part of the tail in the confidence interval, if we can, or reduce the number of times that you might actually end up in there. We're going to increase the number of patients to make sure we see that. We're going to go for four hundred patients, up a third [inaudible]."

You have these 2 drugs out there competing for patients. They're trying to get a clinical trial enrolled. There's COVID going on. They complete enrollment 6 months early. MorphoSys does. AbbVie completes enrollment on time. AbbVie recruited two hundred and fifty patients in more time than it took Pelabresib to recruit four hundred and thirty patients. They ended up actually getting more demand than the four hundred.

Doctors were still trying to put patients in the trial. They said, "We only did it for four hundred." But they didn't want to tell, "Hey, doc, you couldn't put your patient on this drug." Because obviously, it's got a great profile from the phase 2 in terms of that risk-benefit, how much efficacy you're adding versus how much toxicity you're adding.

That was an incredibly positive sign in the KOL community, and especially, there's a lot of excitement for this drug. When we were doing our KOL calls, one of the docs told us, "I know what a Jakafi patient looks like. They come in. They're fatigued. They're anemic. I can't tell you that I know exactly who's getting placebo in this trial and who's getting Pelabresib. But I can tell you that I know there's a certain degree of patients that look different. I can't tell you if they're the placebo ones or they're the ones. But I've seen what Jakafi patients look like." We've been incredibly enthused when we've talked to KOLs about this mechanism.

The other thing that was really interesting is that when phase 2 ended - it was a twenty-four-week study - as soon as you got the twenty-four weeks, they're like, "Here's the top line data. Here is where it's going to go." But they let patients continue. You've got patients on this drug now for 3, 4 years that are having symptoms controlled. Their spleen volume is reduced. They're living a not normal life but much better life. That's durability. It tells you how active the drug is. That was really impressive to us.

There are these 2 big hematology conferences, EHA in the summer and then ASH in December. Every time, they update it. Every time they update their data, they'd say, "Hey, here is our phase 2. Here's how our patients are doing." Patients are staying in the trial and staying on the drug. They're having great control of those 2 efficacy endpoints we mentioned. That to us is another layer of confidence into we think this has got a really high probability of success.

Andrew: I remember, in a prior life, I did some healthcare stuff. One time I was looking at a drug and I was like, "Hey, all the patients are dying after 5 years. Is there something wrong with this drug? What the heck's going on?" They're like, "Dude, the average life expectancy of somebody with this disease is 9 months. If all the patients are dying after 5 years, you're looking at the greatest invention in history."

Just listening to the numbers, you said, "Hey, some people have been on this drug for 3 or 4 years after the trial." It's not just that they've been on it for 3 or 4 years, and the drug isn't really harming them. It's that they're alive after 3 or 4 years seems to be the big thing. Because as we said, a lot of the people's life expectancy here is a year. If you get it when you're younger, maybe 4 or 5 years. But these guys have been on it 3 or 4 years. That's pretty incredible.

Dave: They purposely went after that high-risk patient group. I think in phase 2 - I'm going to have to go back and look at the exact notes; here we go; let me pull the write-up - half their patients were high-risk. Half those patients that they took in their phase 2 were patients that would otherwise have basically been dead in about a year and a third.

Andrew: Obviously, that's all awesome. I might have been misremembering the acceleration of the patient count. I guess let's talk next steps for Pelabresib.

Here we are. I think they complete the enrollment of phase 3 top-line. Results are expected end of '23, if I'm remembering correctly. How do you see this playing out going forward?

Dave: The one thing you always got to think about in our views in biopharma is you're taking 2 kinds of risks, taking risks that your drug works and it's going to continue to work. And you're taking a risk that competitors' drugs maybe work better than yours. Between now and November/December, when their trial's going to read out, you're going to have 1 data point from a competitor, AbbVie, that we mentioned, this drug Navitoclax. That should come out any day now. Their trial stopped in April. AbbVie's a big organization. You got to clean the data. You got to make sure you're doing the right thing. But it should be any day now.

It's really interesting when we dug into Navitoclax. Navitoclax was a drug that was on the shelf with AbbVie for twenty-plus years. The reason was it's a dual targeting mechanism. One of the on-target effects of the mechanism is that it knocks down your platelets. I think we talked about before. Patients already have low red blood cells in a myelofibrosis. A lot of them have low platelet counts because, again, the bone marrow, they produce cells. They produce them all badly. It's not just like they produce red blood cells.

AbbVie was running a phase 3 in combination with Jakafi on top of basically a thirty-two-patient phase 2 study. What that thirty-two-patient phase 2 study showed was they were able to get a better spleen volume reduction or a 35% reduction in more patients than in Jakafi alone. But they didn't really have any improvement on the symptom score. If you looked at the combination of the low platelet counts between both studies, almost a third of the patients had grade 3, 4 thrombocytopenia in the Navitoclax study which docs are going to say, "These patients have enough problems as it is. Do I really want to add that toxicity?"

What we expect for that is it probably is going to show some benefit on spleen volume reduction. The 50% symptom reduction, that's no better than a coin flip if they're going to show any benefit on that. The toxicity is an on-target effect. We think, from a product profile perspective, AbbVie's drug is not going to be as clean a benefit to risk profile of Pelabresib. That's what we expect.

Even though they might be able to announce this phase 3 results - they might be able to apply for an early 2024 launch - we think that from a product profile perspective, Pelabresib is going to be better.

Andrew: That is Pelabresib being better than their competitor. But what about Pelabresib getting approved and launching? What do you think the timing on that is?

Dave: We get them. We're very positive and see some really great top-line results, benefits on spleen volume, benefit on symptom score, low toxicity, addition to Jakafi alone. If they showed good top-line results in December, then you're talking about from then end of year '24 when they're getting approved.

Now, what I would tell you is one of the things we've talked about a lot with all of our LPs and one of the reasons we love the sector is the evolutionary food chain in the sector. Right now, one of the things we would tell you is if you look at big pharma today, $140 billion of revenue is going to come off patent in the back half of the decade. Big pharma is desperate to replace it. Their internal pipelines aren't going to do it all. When you've got assets that have $2 billion-plus potential and they're de-risked scientifically, that's an attractive asset.

Listen. I think if MorphoSys has great data like we think, they've got a viable stand-alone strategy. They're going to be able to do great things as MorphoSys. But we also think that there are a lot of strategic optionality once you've got a de-risked asset that everybody says it's synergistic with a standard of care. It leads to a lot of better patient outcomes. That's going to be very valuable to us.

Andrew: What you're saying there is, "Hey, look. The phase 3 data..." I don't think you've just explicitly said it. I think that they'll announce the phase 3 data in early 2024. It's when they'll announce this phase 3?

Dave: No. Based on what we think, it's late November or early December, before the end of [crosstalk].

Andrew: Then what you're saying is they could and are prepared to launch standalone towards the end of 2024 if they have to. But as you said, the most likely is you do this. Then if you've got to de-risk, "Hey, the phase 3 data was great." It makes sense for all parties, "Hey, MorphoSys, you can either go build out an entirely new sales force, get on this insurance pricing, burn a lot of cash along the way doing that. Or you can sell to Pfizer over there who's already got that." All they need to do is write a check and then they can plug it in and they can scale this up in a second. It actually does make sense for everyone.

On the call that you did, you were mentioning that you were talking to a banker. They were talking about how the evolution of discussing deals and failed deals with boards have gone for big pharma. Do you want to give that story? Or I can jog your memory a little bit more if you don't remember that [crosstalk].

Dave: Oh, no. Yes. That's interesting. The patent clip [?] has become much more acute in the last couple of years. Everybody knows Humira from AbbVie is coming off that's like the biggest blockbuster drug ever. You've got Keytruda at the end of the decade, all that stuff.

There is such pressure on these companies and management teams that whereas before management teams went to boards to say, "Can we get this deal approved? Can we do this," now, they're having to go to their boards and say, "This is the reason why we lost this deal. This is the reason why we didn't bid on this deal. This is why we don't think the science is that great," or, "We think our competitor made a mistake." They're having to justify not doing deals instead of doing deals.

That's a big change. It's a big change in the mindset. When you're saying that more [inaudible] alone, well, they do already have the infrastructure in hematology-oncology with Monjuvi. They got that in the US. They're already in Europe. I think they admit that having it in Europe may not be the best decision in the world. But the one thing we talked about at the beginning is that they've got this partnership with Incyte. Incyte owns half of Monjuvi [inaudible]. They own all of Monjuvi in Europe. Incyte is market's Jakafi, the drug that Pelabresib's being used in combination with that oh, by the way, goes off patent in 2028.

The major blockbuster for Jakafi, the center of Incyte's valuation, goes off patent in 2028. They don't have anything in their armamentarium to replace it yet. You've got this de-risk asset over here with a company you're already partnered with that isn't additive onto your current drug. And you owe them $535 million of milestones if they're successful with Monjuvi that you paid 55% for.

There's a lot of reasons why if this is successful, I would say strategically, people from Incyte's shareholders would say, "That's a good deal. That's exactly the idea."

Andrew: It's a deal that just makes sense for everyone as you're saying. Let's talk real quickly. I think we've talked a little bit of science. You've talked about the pipeline and everything. I want to quickly ask. We threw out, "Hey, we think the risk-adjusted value of Pelabresib is about $45 per share." How do you come up with that number?

Dave: The pricing for these drugs is all in the multiple tens of thousands of dollars per month. We think this is conservative. Because we talked about the beginning. You can add this drug to a patient that's going to get Jakafi and improve their efficacy without any increased toxicity. Why wouldn't a doc do it?

But we said, "Hey, what if they only get half the patients that they're newly diagnosed in? What if we only get the same duration of response that they get with Ruxolitinib?" Usually, your discontinuation rate with Jakafi is about 30% in the first year. Then it of falls off 20% in the second year. Then it kind of falls off a cliff after that or 50% about the second year then it falls off a cliff.

If we only get the same duration of response, we're not able to improve how long these patients stay on the drug which our phase 2 data would say, "Oh, yes. You can," that you get to about a billion-one of peak sales in both the US and Europe. When you look at the precedent transactions- and we've got 4 of them in myelofibrosis in the last 3 or 4 years where we can look at the average peak of sales multiple that companies paid was about 2 times. Then we put that on a probability of success and divide that by the shares outstanding. We put about a 78% chance of success which as you said, you went back to, "Hey, 95% of the time, if you replicate your phase 2, you're going to do better," or actually ninety-seven and a half, because there's the two and a half on either side. Ninety-seven and a half percent of the time, if you replicate your phase 2, you're going to be better than Ruxolitinib. But we're saying, "Hey, let's do 78%." The peak sales times 2 over shares outstanding times the probability of success equals forty-five.

Andrew: On the probability of success. You guys have a slide up here with about 8 different banks you cover and estimate odds of Pelabresib. None of them are below 50% odds that this gets approved. But only one of them is above 70%. Most of them are 50 or 60%.

You said, "Hey, we're doing seventy-seven, seventy-eight percent. We actually think the odds are higher based on the base rate and the data and everything." What are they missing when they threw a 50 to 60% out there versus what you guys are seeing or what the base rate says?

Dave: That's a good question. We tried to talk to some of these analysts. Again, generally, sell-side analysts do a great job. I don't want to pick on anybody in particular. But I think, in general, the coverage of MorphoSys from that diversified antibody is pretty much the same. If you were the analyst to cover the diversified antibody and you cover other European pharma services companies, and now you're looking at this US biotech, it's a very different risk structure and profile than what you're typically used to evaluating. What I would tell you is if you just think logically, they all put 50% probability of success under there. They all have peak sales that's not like crazily off ours, right?

Andrew: Yes.

Dave: Somewhere around a billion.

Andrew: Yours is right in line with the average there. I think we mentioned about a billion to one-point-one billion. There are some people who go up close to 2 billion. But yes. They are all pretty [crosstalk].

Dave: If you took the same math that we did about how we got to our value per share, the value per share of Pelabresib is higher than their price target.

Andrew: I had a big position in Twitter when Elon Musk was trying to buy it and backed out. You could talk to some analysts. You'd say, "Hey, you've got a 60% chance of Twitter winning. How do you come up with that?" They talk a lot. But if you really [inaudible], they'd be like, "Hey, we think Twitter's probably 90% to win." But if we put 90%, the price target looks ridiculous versus the current share price.

I think you have the same thing. I'm just looking. To grab one who's right in the middle, Commerce Bank has a 50% chance of success, a billion in peak sales. They come out with about eighteen or twenty euros per share for Pelabresib. That's about the share price. You get everything else for free. If they put anything else, then they've got to start saying like, "Hey, here's why we're going out on a limb. It looks crazy. Guess what? If you're at 50 or 60% and the drug's approved, you can probably take a victory lap anyway." There's no incentive to go any higher is how I would think about it.

Dave: UBS just initiated coverage end of May. They were a little bit more intellectually honest. They came out and said, "Hey, we think you're getting Pelabresib for free." They put a EUR47 price target on it.

Listen. I think people are starting to wake up. The one thing people always talk about like what do you not like about the sector is you have companies that go into this catalyst desert. You report something great. Everybody was like, "You report something great. All we want is instantaneous. It's going to translate to revenue."

That's just not how drug development works. You report something great. Then you're going to go test it in a larger sample size. Then you're going to go out. Then you got to go talk to the FDA and EMA.

MorphoSys had this horrible transition in the shareholder base post-Constellation. Then they went into this not a quiet period. But there wasn't a lot of catalysts. They're just focused on enrolling the study, getting the right patients in, getting them on drugs, recording the results. That's who we are. But now, you're starting to wake up, "Hey, we're 6 months from data." Like, "Okay. People start to wake up."

Andrew: You definitely see it in the US especially when you're a month from data. All of a sudden, the volume picks up.

Dave: That's true.

Andrew: The zero-day options traders start buying it. I want to ask 1 more quick question, because obviously, they got this drug from buying Constellation. There's just one thing I think is worth noting. The Constellation sales process, obviously, there was a proxy involved in everything. I just wanted you to speak to the Constellation sales process. Look. It was back in April 2021. Obviously, a lot has happened since then. But I do think you can learn something from the Constellation process if you want to talk at all about that.

Dave: We went back through and looked. It was competitive. There were 4 bidders. The process was accelerated. MorphoSys helped that along. They'd had a lot of partnering discussions that Constellation had that turned into offers.

When we combine that with you look at all the other transactions in the space, whether it be Sobi buying CTIC, GSK buying Sierra Oncology, Merck buying Imago, there's a lot of interest in this space from larger pharmaceutical companies, because there's an unmet need. People really recognize that Jakafi is great. But if it only works for 40% of patients to help their symptom score and help their spleen volume, there's 60% of patients out there that aren't having disease control. That's so high.

Andrew: I have not done a lot of Jakafi. But it crazy. You've got an approved drug first line that only works for 40% of patients.

Dave: That's it.

Andrew: That's great. When I think of a drug like, "Oh, yes. It works for 85% of patients," it's crazy that there's a first line that's only 40% of patients.

Dave: To be fair, Keytruda which can be, on phase 3, the best drug ever, probably only works about a third, thirty-two, thirty-four. Again, we're all trying to discover more. That's a great part of the industry. It's trying to elevate standard of care for these patients. They keep bettering on it. I think the next immunotherapy will be better.

I think Pelabresib will be great in terms of an add-on. That's great. We got a lot of room for improvement. People will pay for that. It's good for payers. It's good for patients. It's good for shareholders. The triumvirate all wins.

Andrew: Before we wrap up, we'll talk here quickly. You mentioned one of the first things you told them to do when you started to engage, you said, "Hey, we should tender for the convert bonds outstanding." They went into that pretty quickly I think you said at a price better than what you said. Just want to talk about the convert bonds that they took out, why this was such an accretive transaction. There's a story about some of the holdouts that I think might be interesting to people as well.

Dave: They had a basically zero-coupon bond outstanding that they had issued when capital markets were frothy. It was great. Good transaction. Good for them.

Andrew: Look. I hurt my back. I've only been able to bike a little bit recently. I might only be riding my peloton right now, because they issued some zero-coupon bonds in February 2021. They might be gone without that.

Dave: That's awesome. MorphoSys had issued a convertible note, a zero coupon. It traded down. It was probably about EUR120 conversion price. As the stock had tanked, this had all gone down. It was trading in the low sixties.

I think we said, "If you bought it back at seventy-two, you realize a 22% IRR relative to just letting the bond out thin. If you bought it back at discount, you amortize that discount over the time and maturity of the bond," that's a good use of capital. Twenty-two percent IRR is a good IRR. That's great.

They ended up buying about a quarter of their bonds back for EUR64. When they went out to try to get more, they had some convert holders who told them, "No. We actually think you might get back to one-twenty."

One thing we didn't talk about is some of those twenty-eight programs, they still have partnered those out. There's value that we are not ascribing anything to. Maybe that's not fair. That's not what we do. It's not how we think about things. But there are options in their portfolio that are not baked into our forecast.

Andrew: If you're a convert bond, and you're a bondholder, and you say, "Hey, I've got this thing. Yes. It has to 6X to get in the money. But do I want to hold out for a 6x and get a 22% IRR to par value? Or do I want to tender this company?"

It's not guaranteed. It's not triple A. Everything could come out bust. They could burn a lot of cash. But it's always hard to give up that 22% plus a kicker bond. It's my guess. But yes. Cool.

Dave, I think we've done a really nice job covering most of MorphoSys here. Anything else you think we should be talking about or that listeners should be thinking about here?

Dave: No. Listen. I think we've got a good company, good asset, good price, good management team, really disciplined management team that's doing the right things. That's one thing that we think is really important. Give them credit, all the kudos in the world. They got to execute. They got to flip the data card over. But they're doing everything right. That's important to us.

Andrew: Awesome. Dave, this has been great. This is a really fascinating story. It's a cool drug. It's cool to see a drug that seems to be doing a lot of good that could create a lot of value for shareholders, too. It's really great having you on.

One day, there's a company you're on the board of that I'm very very interested in that I don't think you can talk about it now. But one day, we're going to have you on and talk fully about that company, because you want to talk about - it's not data - near term things that could happen there. Listeners can look it up. They'll know what I'm talking about if they do a little diligence.

But Dave, I really appreciate you coming on. This has been super helpful. If anybody wants to reach out on this, there are ways to find you. Looking forward to having you on for the third time in the near future.

Dave: Thanks so much for having us. Good luck doing it. We love all the diligence you do to prep for these things. It's a lot of work. We really appreciate it. It's really great to talk to somebody who's so informed about it and got great questions. We really appreciate it.

Andrew: This time it was mainly because you guys gave me everything to do before. But it was awesome. Dave, we'll chat soon, buddy.

Dave: Be well. Thanks, Andrew.

[END]

Hi Andrew, I too hope the phase III pelabresib trial is a smashing success. But the discussion above--and please correct me if I am wrong--appears to compare findings from the phase III ruxolitinib study, published in NEJM 2012, with the more recent phase II study of ruxolitinib plus pelabresib study published in the JCO in 2023. If so, please note that the landmark ruxolitinib registration trial patients were quite ill. 68% were pretreated with a leukemogenic chemotherapy (hydoxyurea), a regimen now rarely given first line (presumably few to none of the pelabresib combo cohort received this). 58% or the ruxolitinib patients had IPPS high risk disease, versus 16% in the phase II pelabresib combo cohort. None of the phase III single agent ruxolitinib patients had low risk disease, versus 24% of the patients in the combo phase II trial. Some of the phase III ruxolitinib patients were ECOG category 3--unable to work outside the home and capable of only limited self-care. None of the phase II combo patients were this ill. So yes, 68% of the patients in the combo arm versus 42% in the ruxolitinib arm had a 35% or better reduction in spleen size...but the patients were healthier to begin with, and potentially more likely to have a beneficial response. Or is there a better comparator trial I am overlooking?