Creek Drive Capital's Kevin Mak on why $PGY has been largely ignored by the AI hoopla (Podcast #174)

Kevin Mak, CFA, Founder of Creek Drive Capital, discusses his thesis on Pagaya Technologies (NASDAQ: PGY), a company that uses big data and AI to look at people's credit scores and look at people's different credit factors to determine whether or not they are more credit-worthy than what would be otherwise seen in this traditional lending system.

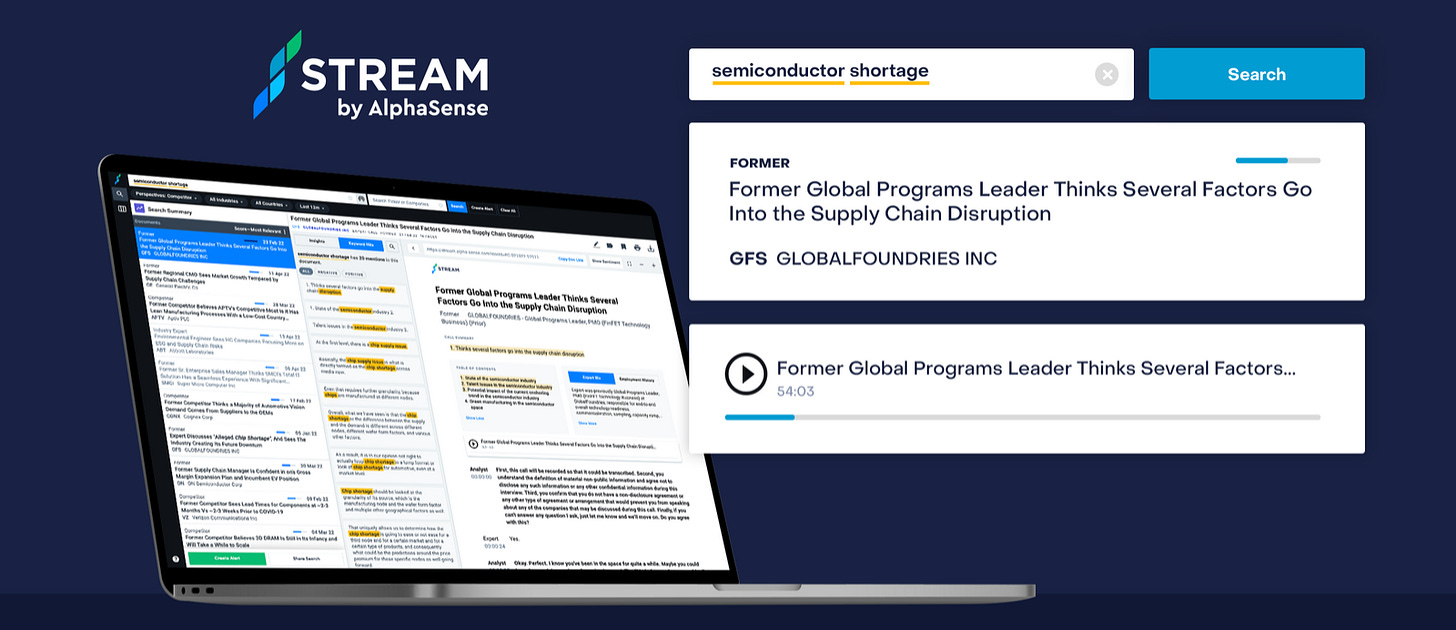

***This podcast is brought to you by Stream by AlphaSense.***

Expert calls just got easier.

Say goodbye to traditional expert networks with Stream by AlphaSense. Stream enables you to access high-quality expert insights, in less time and at lower cost. With proprietary search technology and a library of more than 30,000 expert call transcripts, Stream provides the tools to help you make smarter decisions faster. Sign up today.

Please follow the podcast on Spotify, iTunes, or most other podcast players, as well as on YouTube if you prefer video! And please be sure to rate / review the podcast if you enjoy it, or share it with someone else who would enjoy it (more listeners is a critical part of the flywheel that keeps this Substack and podcast going!).

Disclaimer: Nothing on this podcast or on this blog is investing or financial advice; please see our full disclaimer here. The transcript below is from a third party transcription service; it’s entirely possible there are some errors in the transcript

Transcript begins below

Andrew Walker: All right. Hello and welcome to the Yet Another Value Podcast. I'm your host, Andrew Walker. If you like this podcast, it would mean a lot if you can rate, subscribe, review whatever you are watching or listening to it. With me today, I'm happy to have on Kevin Mak. Kevin is a Portfolio Manager at Creek Drive Capital. Kevin, how is it going?

Kevin Mak: Great, Andrew. Thanks for having me.

Andrew: Hey, I've been trying to get you on for a while. I'm really excited to have you on. Let me start this podcast the way I do every podcast, that's with a quick disclaimer. Nothing on this podcast is investing advice. Neither of us are financial advisers. Please do your own work. And you know, every podcast it's true, nothing's financial advice. But today, we're going to be talking about, it's not quite a penny stock, but it's approaching there. Actually, the company has a pretty solid market cap, approaching to a billion-dollar market cap, but it is a low-dollar price stock. So, people should just remember that probably comes with extra risk. Please do your own work. Not financial advice.

Anyway, let's turn to the company we're going to talk about. The company is Pagaya Technologies. The ticker there is PGY. Kevin, I'll just toss it over to you. I guess I'll mention you wrote two articles up on Seeking Alpha, which will be included in the show notes for anyone who wants to see that. But I'll toss it over to you. What is Pagaya and why are they so interesting?

Kevin: Sure, let's start actually reverse a little bit, which is let's start with a bit of a process and exactly what you were leading to in the beginning, which is why am I looking at this place, this company, in the first place. And from a process perspective, what I've tried to look for is I look for situations that are structurally going to allow for mispricing. So it doesn't matter how much I'm interested in this specific situation called Microsoft Activision. I'm like, there's no way I could compete here. And Pagaya is one of those where the more I looked into it, the more weird things that happened to a company, where I'm like, okay, well, this is the reason why a mispricing is possible.

And so, as you said, it is a company that has a stock of price for a buck 20, and it was below a dollar just a couple of months ago. It was an international company, so it files foreign filer, and it is a ex-PAC. It also works in a space that people generally find icky and opaque. And so for all these reasons, it doesn't matter how good the company is or how bad the company is, a huge swath of the investment realm is going to just absolutely categorically ignore it. That is what creates an opportunity here.

Andrew: Look, I don't disagree with you because when I looked at it like phone a dSPAC, like I vomited in my mouth a little bit, we'll probably talk a little bit more. But their most recent earning calls they had, the end of it was they asked ChatGPT to form a question and then form the answers to that question. They said we're an AI company. When they did that, I didn't just vomit in my mouth, I vomited on my computer a little bit. It was crazy.

Kevin: I get it. It's certainly a little cringy. They're generally trying to lean into the AI world a little bit. That's actually an interesting one there alone, which is like they are an AI company. They have been an AI company for a while. They're an AI company that uses AI actively today to make money, yet they're largely ignored by the AI hoopla for a few reasons. One is they have revenues, so pre-revenue companies are always more fun than revenue companies. And also, I wouldn't even say the older style of it AI, but it's not large language models. It's still statistical inferencing. It's still all of that that had the AI does with big data. It's just using numbers instead of words. Instead of trying to predict the next word to descendants, which by the way it's like large language models do fantastically well, it's trying to predict whether or not somebody's going to be able to pay their next payment on their auto loan or their consumer loan.

So, let's take a step back. What does Pagaya do ultimately? They use big data and AI to look at people's credit scores and look at people's different credit factors to determine whether or not they are more credit-worthy than what would be otherwise seen in this traditional FICO score lending system. They're called a second-look loan provider. To boil it down as simply as possible, they'll go to an auto dealership and say, hey, you currently get a thousand applications every week, you approve 25 of them, and they walk away with cars. You have 975 of them that you declined because your current underwriting system, your current bank, whoever it is that you're working with, doesn't want to give the loan to the person because their credit score is below 675 or 640 on FICO or whatever.

We're willing to look at that as a second look and say, yeah, your credit score might be a little bit lower than what the cutoff is, but you have these other factors that we believe, or our AI believes or AI has figured out, make you credit worthy and worth bumping you up into a place where we can lend to you. Maybe we need a slightly higher interest rate, maybe not. All that kind of stuff. Ultimately, what it means is that they're sourcing these loans through their what they call are partners, and then they're helping the partners out because the partners are getting incremental revenues via their sales or via a loan channel or whatever you want to call it. And Pagaya is getting a loan out to someone who otherwise would be ignored by the traditional financial system giving the traditional scoring system.

Andrew: Just one question on that, and I want to dive into a lot of things by tangent to that. But just one question. You mentioned if you're an auto lender, and auto lending is a big piece of what they do, if you're an auto lender, you put in someone's credit score, you put in someone's info, initial loan gets turned down, Pagaya is basically a second look. They are a second look. They mentioned so many times on their call we just had in 2022, we formed a partner with Ally Financial, who I believe is the largest auto lender in the country. Is the partnership Pagaya is forming, are they trying to go out and form a partnership with the auto dealership or are they just getting the second look from Ally? Because I thought it was the former, not the latter. So, it's the latter, not the former.

Kevin: So, it's the latter, not... sorry, Ally or the dealership you're saying? It's with Ally.

Andrew: I thought it was with Ally.

Kevin: It's with Ally, yes. I'm skipping a step just to make it more straightforward for a firm partnership. So that's their system. Ultimately, the value add up at all of the channels. Is that the person who wants to get a loan is getting some money, the person who wants to sell a car is gaining on selling someone a car, and then the investors are being to underwrite that. Importantly, and then this is where things start to get kind of messy, right? We have a lot of 2008 vibes where you're no income, no job, mortgages that were just being predatorily given out to people, you collect a ton of fees at the front end and then you get screwed to the back, but you've already taken your bonus and moved away. And that's a world of credit in general, which is that these tales are hidden. You are completely unaware of them. You kind of just have to go ahead and trust the company. And to this day, I would say that's probably one of the biggest problems that exist with Pagaya, which is it's always going to be a situation where you just have to trust that they are doing the right job with their underwriting, which certainly lets people be a little bit uncomfortable.

Andrew: No way, it's a great point. And certainly, a lot of the podcasts recently have been focusing on financials and banks. The scariest thing, as we learn over and over again, the scariest thing in finance is a quick growing financial because it used to be just because, hey, if you're a fast-growing financial and your loans go bad in two or three years, and you can pay for that over with a lot of growth. But it also became if you're fast-growing financial when you take on a lot of deposits, there's risk there too. [crosstalk]

Kevin: Let me break you out. Let me cut into there. So what's unique about Pagaya's model is that they don't take on much balance sheet risk with what they're doing. They do something called a pre-funded model, which is pretty uncommon. And so, what they'll go out is they'll go to the ABS market, aspect security market, and they will go to their investors and say, we're raising an aspect security of $500 million.

I'm not going to go into the tranching and all that stuff for your listeners, some of them understand that some of them don't, but they'll collect $500 million from hedge funds, banks, and sovereign wealth funds. All those people they'll dump $500 million into Pagaya and then the guy has that money. Then they'll go out and make the loans with that money. And so, a typical lender is going to put it on their own balance sheet. Maybe they will securitize it after and get it off their balance sheet, but maybe they'll keep it on their balance sheet. Pagaya specifically keeps it off their balance sheet with one exception, which is they need to keep 5% on their balance sheet as the Dodd-Frank regulatory risk that they need to keep.

However, what's really funny about that is that this isn't in any way illegal, this is just a funny, weird loophole. They have a non-controlling interest that's invested directly into Pagaya that is essentially taking the risk of that 5%. Although the goal is to have 5% of it on the balance sheets so that there's some incentive for the company and equity investors not to underwrite bad loans, they've actually managed to offset a large portion of that risk through the NCI.

Andrew: I think there are three questions that's going to jump to anyone's mind here when they research it and look, they're the three questions that jumped to my mind. The questions are going to be a combination of valuation, business, and macro. I guess that's probably the questions that jump out to everyone, but it's pretty true here you should hear and I think these are ones. Let's set macro to the side. I'm sure everybody knows a little bit about what's going on in macro. We'll talk about it at the end and it does really matter here.

But I just want to start by talking because this is important as people think the AI play, the growth, all this, it is important to baseline. I think one of the reasons you're interested in it and one of the reasons I've heard from other people that are interested in is like, hey, man, forget all the growth things, forget everything else, is this just really damn cheap on an asset basis?

We can walk through the math where they think they can get to 700 million EBITDA and everything, all this sort of stuff. But why don't we just start by talking about the cheapness on just an asset basis because you're probably not paying much more than liquidation value as you put in your article?

Kevin: Yeah, and that's what's interesting. I've been getting deeper into this company over the last two months. It's my first article and you can see the evolution of my knowledge and the way I'm collecting that information all over time. My first article, I had effectively very little fundamental view on the future of the company. The stock was at 80 cents. And the primary part of the article was that, look, this thing is trading roughly at liquidation value. This 5% regulatory risk thing is scary for anyone who isn't looking at the company because it could be worth 700 million or it could be worth 200 million. I have no idea. But when you talk to the company or read what the company's written in their reports, first of all, most of that $700 million has been pushed off onto the NCI. And second of all, what's left is like AA-rated, Tranche A, ABS that is pretty much good as cash.

And so, that was the 80 cents. And so, to me, it was something you could just buy for basically free upside. And then the even more extreme was that once in the trading dynamics of the stock, the vol was 120%, which meant the puts were really, really expensive. And the borrower rate is 40% still, which means that if you just hold the stock, you're collecting a huge yield for holding something at cash with tremendous growth as well, which is in the last three years, the company is 3x its revenues. One of those screaming trades for me, was just selling a ton of those puts. I would say I haven't seen another situation before ever where you can sell a put. If the stock goes to zero versus if the stock stays flat, you make 25, 30%. It was over two months. It was just a really wonky situation.

Now, I will stress that we're at $1.20 now, not $0.80, and this is another part where people sort of don't give penny stocks credit. I don't care about the leading digits, I care about percentages and we're going from 80 cents to $1.20. We're 50% higher. The risk is significantly higher now than it was two months ago, and as a result, you need to be much more careful. This goes on the upside too, which is when I tell people I think the stock's going to $2, they kind of shrug. They're like, eh, $1.20 going to $2, whatever. But that's the same as saying a $60 stock's can go to 100, and that usually gets people really excited.

And so, I'm excited about it just because the upside in this thing, I don't even think two is the right number, I think 2.53 is the right number, it's absolutely immense. But yes, it was trading near liquidation value and most likely for the exit. Mainly for the same reasons that I mentioned at the very beginning of your podcast. And also because we have seen that Tiger basically aped into this stock in the 2021 days, took on a huge, huge $300 to $400 million position, and has taken an absolute bloodbath on it and has been liquidating their position. Not obvious they've liquidated 100% of it, but they've filed that they've liquidated 20 million shares under their 65. And there's plenty of press reports saying that the Tigers' clients are being hit by redemptions and need to keep trimming their portfolio. So, [crosstalk] it wouldn't be surprising.

Andrew: It's just funny you said they had a three or $400 million position because this is an 8 or 900 million market cap company right now. [crosstalk]

Kevin: Sure, yeah.

Andrew: So, very upside down in the position.

Kevin: It was an $8 billion valuation at one time during the crazy times. And that's another interesting one, which is the stock looks ridiculous. It went from 10 or into 30 to a dollar. Ten was probably wrong. I mean, probably it was wrong, but it was comped correctly against Upstart, which we can talk to later. So 10 made sense in the context of the market at the time. And then obviously, things went to shit and other financials, fintechs, also took a fair chunk of hits there.

Andrew: There are a lot of questions, but let me just start. A, I guess I should remind everyone, Kevin mentioned puts and intrinsic volatility. Again, not financial advice, puts and options and everything, absolutely carrying added risk factors. So, please consider that if you're looking at those or anything. B, I do just want to ask and say, you mentioned short interest off the chart, right? For a company that was trading around liquidation value, it's a chunky shareholder base here, but it's not like the free flow to zero here. Why is the short interest so high? [crosstalk] [inaudible]

Kevin: Sorry, short interest itself is not high at all. That's the weird part. The short interest itself, even if you look at a free float-adjusted basis, it's tiny. Back then and even right now, there are about 8 or 9 million shares of shortage. On a dollar stock, that's a $10 million notional size of the trade. Any tiny hedge fund can be short $10 million of this thing. The borrow rate being 40% is what doesn't make any sense. And I can tell you, I'm watching reports every day. I collect that a good chunk of that 40%. In fact, not only do I collect a good chunk of that 40%, but at least with my broker IB, they round the collateral up when they calculate borrow rates. So, if you're lending a stock that's worth $1.20, you collect collateral based on a $2 price. So, a 40% borrow rate is charged at $2, not at a dollar, so you double, which is great economics.

I know I might be boring some people. [crosstalk] [inaudble] Some people whose eyes were like our fund we care about every 10, 20 dips here and there and we're playing this trade for three or four months. When we originally just looked at the math on it, we're like, on the ball or on the borrow rate or whatever you want to say alone, we're picking up 17%, which we think is pretty close to alpha. Never mind what happens after that.

Andrew: That covered the interest of value. I guess this starts to transition to business quality. But you mentioned how pay at 80 cents you were paying barely above liquidation value. The company has come out and they've said, hey, they're adjusting EBITDA breakeven guiding to adjusted EBITDA profitability for this year. They were profitable in 2021, but that was probably a little bit of best of all times. 2022, they were just below just the EBITDA breakeven. Obviously, there's a stock comp and everything, but I'm just referring to this because you've got a company that is trading barely above liquidation value. You've got a company that is breakeven or growing and they raised, I think it was $75 million of prefers that will flip over to common after shareholder approval. I think they might've already got shareholder approval. But they raised $75 million of equity at about today's prices basically.

As an investor, I look at it and I see you've got a management team that's out here saying how cheap they are, how quick they're growing, how good their asset base is. You've got Kevin who's out here who's saying this is a cheap company, they've got growth potential, there's a lot of optionality here. And then they're going out, they don't have a debt problem. They don't have any problems, and they're going out, and they're issuing stock pretty aggressively. I look at that and say it all sounds good but they're going out and issuing stock like what the heck is going on here? Are they really shareholder-focused? Are they trying to build an empire? Maybe it doesn't super matter from today's prices with as you said, the borrow you're collecting and the volatility and everything, but from a fundamental case, I look at all that and I say that is just really funky.

Kevin: Sure. Doing the convert, I think I wouldn't call it that aggressively. At the time, the market cap was around $600 million. They did a $75 million convert. I will note that the company is capital hungry because of that retention requirement, which is if they want to underwrite a billion dollars worth of new loans or new ABS, they need to keep $50 million of that on their balance sheet. Now, that recycles the capital. So right now they have a huge bunch of their older loans that are coming back. But growth will require balance sheet space kind of like on a working capital basis. They have revolvers, they have that kind of stuff. Also, that was a convert. So, it's like a debt issuance, but at the same time, an equity issuance. [crosstalk]

Andrew: I think, it was a preferred convert, right? [crosstalk] Yeah, it was a preferred convert. So, it's going to convert to equity. I think for all intents and purposes, you can think of it as equity.

Kevin: Yeah. And then they did it at a pretty good rate. It was the stock was at 95 cents at the time and the strike was a buck and 25. So it wasn't overly predatory. It was also done with a pick on the interest side of things, so it wasn't going to hurt them. They said that they want to do M&A. I've been in touch with management multiple times now. I've told them that I don't think the market would be supportive of them doing M&A. I know what they're saying, which is they're like we're valued at crazy levels and some of our peers are valued at crazy levels. So, we would love to be able to take advantage of these extremely depressed multiples by someone else that's trading the basement like us, because we're going to ride the wave up in the next year or two years, three years, now that rates have stabilized, or now that rates are heading lower and things like that.

Andrew: Let me just go back. You mentioned they were capital hungry, right? They've got the risk retention portion and everything. I certainly hear that, but as a lot of investors like to say, it's not free cash flow growth, it's free cash flow growth per share or value growth for sure, whatever you want to call it. And I certainly hear you, hey, they've got a lot of growth opportunities, they have to retain 5%. Even though they can get around it with [crosstalk] [inaudible]. But I hear, hey, we want to grow a lot. We're going to grow issue a ton of equity. And they're telling you, hey, we know we're valued at crazy prices. And I hear that and I say I see a company more interested to me in empire building than a company interested in creating shareholder value. Or they say, hey, we want to go buy our peers at crazy prices. And I believe they said on their Q1 call, we raised this money in advance of going to buy a peer. It's like, well, okay, but you raised money. You locked in shareholder dilution at what you're saying are crazy prices for the optionality of maybe doing M&E.

It just kind of concerns you. For a normal company blow or whatever, but I do think it's got the foreign company, it's got the SPAC wrapper. And then you see them issuing equity you're like, oh, just another red flag, you know?

Kevin: No, I think that the criticism is totally valid. I do think that from a growth perspective, if they do want to grow their loan book significantly, you don't want to have to rely on the NCI, you don't have to rely on being able to get the money there. So I think that the extra $50 million as a buffer is nice. I agree, it does dilute. And there's some mixed signals there.

But if they want to be growing at 30, 40%, which is what they arguably are implying, they are absolutely going to need that. And the EBITDA coming from those billions of dollars of loans they plan to write should make up for it. But yeah, it would have been nice to do a straight debt offering and I would like to see that happen in the not-so-distant future versus doing something like this for [inaudible].

Andrew: Let me ask. Turning to the business, so the business is, as we mentioned, they do it for all sorts of things. They do it for buy now pay later, they do it for personal loans, they do it for all sorts of things. But I'll use Ally Financial because that's the example I chose.

The business is, I go to Ally and I go to a dealership that's got a relationship with Ally. I apply for a loan. I get rejected by Ally Core for some reason. Ally gives Pagaya a second look and Pagaya for one reason or another. And they mentioned something like one, they mentioned is Ally might require seven years' worth of credit history and I only have six and a half. So that's not that big of an increase in loan, but Ally just flat rejects it, Pagaya would have approved. But they mentioned a few others. But so, Pagaya gets the second look, Pagaya approves it, they fund it with ABS they've got, and then I get the loan.

And I guess my question here is, look, Ally is enormous and a lot of their partners are enormous. Ally, I looked this morning, $200 billion in assets and assets on their balance sheet, every year they spend over $400 million on tech investment. They are definitely familiar with the ABS market. They do some ABS. They're the largest car loan.

And I guess when I look at Pagaya giving the second look and approving it, I just look and I say, how can Pagaya actually approve and fund a loan that Ally has looked at and said, I can't approve and fund this loan properly? It just seems like I have trouble believing Pagaya's technology is this much better, that Pagaya has this much better AI, all that sort of stuff. So how does that work?

Kevin: Yeah. I think you might be comparing size with competence. And my experience is that just because you're bigger doesn't mean you're better at being sharp. You often use that size as to your advantage in market power. But when it comes to something like credit ratings, you have to actually ultimately pay the piper kind of thing.

We talk about the ABS side of things. Pagaya is number one in ABS issuances in the consumer space, not the auto space, but the consumer space. Banks need to be very low-risk. Taking a risk is something that banks do not want to be seen as doing, especially in today's climate. And it's just they've decided that we want to do what we're used to doing, which is using the same scoring system that's decades old.

Pagaya has recruited people from these big banks that work on these loan desks or these personal desk auto loan desks. Presumably, because these people have seen how they work at the larger tier-one institutions and said, I know we're leaving money on the table, but at the end of the day, we don't. I do think that it would make sense for these guys to reach down and increase the credit box to include some of these loans. And then the question is, what do they then do? Do they build or do they buy?

Arguably, one of these guys can just buy up Pagaya, and that's going to be cheaper than building your own thing, and you could apply it to your own massive loan funnel and immediately print more from that than you paid for Pagaya. Because as you said, these guys are absolutely massive.

Even in the integration process, when they sign some of these dealers, they only send a portion of their flow to Pagaya. I don't know exactly why I'd like to probably clarify that with the company, but it takes time for them to sort of fully send all of their flow to Pagaya. They have no balance sheet risk. It's purely incremental at that point in time. It's something you were to throw away in the garbage or send across the street.

Why you wouldn't basically set 100% on Pagaya on day one? I don't know. But that's also the math that the guy is using, which is like we signed three massive partners last year. We're only seeing your 20, 30% of their flow right now and in the next year or two, assuming that we're still doing a good job, they're all going to convert to 70, 80, 90% of their flow coming our way and we're going to immediately have 3x, 4x the amount of applications which we can approve and collect fees and all kind of stuff.

And also, they show that their partners are sending more of their loans to Pagaya, which is that they're like, these other loans they're kind of borderline for us. We used to take them but now we're going to start sending them that way because we would rather just collect the fee and not have the balance sheet utilization or risk and keep capacity for other things.

So all of this is kind of the reason why. I will say that this stuff is somewhat qualitative hand-wavy. I've never been a loan officer, I've never been a loan strategist at these things. So it is very much secondhand. And this is also what makes your questions are totally valid, and it was what makes equity investors like myself nervous, which is that we are investing into an equity.

But this equity has this massive exposure to the credit market and the nuances of how the credit market works, which is very much of a black box to me and to other people, unless you've been in it for a long time. So I have been trying to collect a list of people who have been in that market to talk to them more about, does this make sense? Is this something that you would have done? And why does it make sense?

For the exact same questions that you're bringing up. I mean, also the part of the question is like, they've done it and the numbers have shown it. So the existence of this market isn't really a question.

Andrew: I do agree they've done it. But I guess I worry because at every bank, like I've been looking at a lot of banks recently, every bank I see is pulling back. And they're specifically pulling back in the auto market. I was just reading Ally, they were at Morgan Stanley literally two days ago, and they said all of our peers are pulling back from autos broadly. We're pulling back from a lot of autos, and we're really focusing on the super prime space because that's where we're actually seeing the best risk-adjusted returns right now.

And I look at every bank pulling back and even Ally who is very focused on it pulling back and say, oh. And then, also banks are funding with large deposits whereas Pagaya is funding with largely hedge funds and sovereign money, which obviously has more cost of capital than a bank. And I look at those two and I'm just like, look, either Pagaya right now the loans they're funding are going to be some of the best in history because everyone's pulling back and they're leading into the same piece, and they do have smart money funding, or it goes back to the fast-growing financials where Pagaya is out here.

We don't have tons of data on how Pagaya does through all cycles because they really ramped up their business in the past two or three years. Maybe they're just doing tons of loans right now and 18 months from now, they're going to say hands up, all the banks pulled back for a really good reason, used market went down, recoveries were awful, a charge loss. They pulled back, we didn't, we didn't blow up, but our ABS investors did. But guess what? We can't fund like ABS loans anymore. [crosstalk]

Kevin: There's definitely a situation where all the lead balance sheet isn't terribly at risk. If the ad doesn't work, the business is broken. And so there is a very big X factor that you got to trust there. You know, you're talking about everyone pulling back and I think that that also goes to everyone's pulling back because everyone's like we kind of indiscriminately approve based on relatively older style systems and we haven't invested in the tech to get this stuff to be really sharp. And big guys like, we can jump in and we can cherry pick the loans that you guys are not approving and take it. It is definitely fair, either they're great or they're shit. And unfortunately, time will tell and there's no other way around it.

I do think that the equity investment does give a pretty good risk reward and view on that, which is if they do grow massively and if their AI does work, then you are going to anywhere between three and eight X of stock because if you start getting that size in, then you're going to be able to use market power, get more data, be able to get sharper, and everything like that.

So I would love to learn more about the inner workings of Pagaya's competitors and how their credit box works, and then how their credit scoring works. The tangent, the stuff I've heard so far is that it's not terribly sophisticated and the reason why is because, once again, you have so much market power, so much basis that you have a cheap cost of funding you can kind of just write loans based on some system that isn't terribly sharp that will still do well.

Andrew: I do hear, I am just very skeptical. [crosstalk]

Kevin: I want to also throw on something, Andrew, which is, I am not a macro investor very explicitly. So I absolutely see all the stuff right now, but we're absolutely overextended, we're absolutely whatever. I used to play that game. Nowadays I generally play the game that I don't know, you don't know, we don't know. And so, I try to avoid taking too much of that [inaudible]. [crosstalk]

Andrew: No, I certainly hear you there. To me, I look at Pagaya and I say great skew. As you said, you're probably trading 50% above a liquidation value. I just like, Ally, Capital One, I'm really skeptical that they're only funding on FICO scores. I think they're really sophisticated and I just have trouble in my mind being, hey, Pagaya's got a better box that is like so much better at underwriting loans that they can profitably fund these loans. But you know what? They've been doing it. I guess I just worry like the history was '21, '22, like used car values are ripping, the consumers super strong. But as soon as you have a little bit of stress, I'm worried that the legacy guys could... I'm skeptical that this bad underwriting that you can get this much. [crosstalk]

Kevin: I don't think it's this bad, by the way. Andrew, I'll throw that in, which is, I think the conversion rate that Pagaya guy takes on their second look is somewhere in, I want to say one to 2%, and then they've cut that by half by half. So it's not like these guys are leaving a lot on the table, it's that they're able to jump in and be very opportunistic about. Out of those a hundred loans you're throwing away, I'm going to take two of them. Ally doesn't care about getting that sophisticated on that. As you said, they're so big.

Andrew: Yep. I hear you. No, it's just a little [inaudible] [crosstalk].

Kevin: I like it because this conversation is something I have regularly and this is what I identify at the beginning. It's in a space where there's a ton of opaqueness and not only is that opaqueness in you, you got to trust the company's AI, but you also have to trust all of this ABS credit market, inner workings that most people have no idea about how it works. Myself included for most of that.

Andrew: Let me go somewhere else. So, the ultimate bull sase, and they laid this out in their Q1, I believe it was the Q1 call, maybe it was the JP Morgan commerce they were [inaudible], but the ultimate bull case is, hey, right now I think we're funding about $3 billion in annual. No, sorry. Network volume is 6, 8 billion. [crosstalk]

Kevin: Eight billion. Yep.

Andrew: They want to take that up to 25 billion and they say, look, we take it up to 25 billion, we get three to 4% gross margin on that, call it a billion of gross margin, $300 million in OpEx, that brings us to $700 million in EBITDA, right? Right now the company's under a billion dollars market cap. So you're kind of talking one times EBITDA at that point.

Kevin: Yep.

Andrew: What do you think about that bull case scenario that they're projecting there?

Kevin: Yeah. I think anywhere in 30, 50% chance, probably I'd be servicing 30. And more importantly, what I would say is well, is if they get the 25 billion, then there's nothing stopping them getting 40 billion or 50 billion kind of thing, which is if they get to those levels of growth now. And then how do you get there from seven or eight? I mean, if you look at the previous growth, it went sort of one, four, seven, and then it's seven. They very intentionally pivoted down to eight, which was last year they saw the Federal raising rates. Raising rates environment is not necessarily bad for them per se, but it's a lot of volatility, right? And so I would say that they were very cautious. They purposely cut their conversion rate massively, tightened up everything that they were doing, and they fared through that quite well relative to their competitor. Like Upstart did the traditional thing you're saying, which is, hey, things are going well, let's crank it. There's 1,000% growth in one of the quarter over the course and that's what pushed the stock to $300 per share or whatever. And then right after they're like, holy crap, we underroll way too much, now we have this huge problem.

They immediately had all of their investors pull off and they couldn't get any external funding. And then they had a bunch of losses on their books, and now they're recovering. And so their revenues went way above Pagaya's and now they're way below Pagaya's. And so, when you talk about the stereotypical FinTech that's fast-growing, that is throwing caution to the wind. I think that that's a perfect example of it, at least the numbers show that, versus Pagaya has been more careful. And then I think or hope once we get through this current climate, we're going to pull eight. We're going to one, four, seven, eight. I could see us jumping to 11, 14, 25 kind of thing in the next two, three years, assuming they turn on all the dials and assuming that they're okay with everything.

Andrew: Just two things about that. I guess just to my points earlier, I was really focused on the car loans and Ally, but we should know that they do a lot of other lending as well. They do a lot of personal loans, they've got a partnership with Klarna, so it's not like it's only auto lending. I actually think you've probably gotten better. I think they've got a better edge in underwriting small-dollar personal loans, going to orders [inaudible] my high level. But just so people listening, it's not just Ally.

The other thing, you mentioned Upstart. I do just want to mention, there's the famous CNBC thing where somebody's like, ambush, ambush. And they're like, what do they do? And he's like, uh. Upstart is a good comparable. And I'm just looking at Bloomberg, Upstart, three or four billion dollar market cap in enterprise value, still burning money. They're trying to get to EBITDA breakeven this year. Pagaya is already at EBITDA breakeven or profitability. All that's adjusted, obviously. But are you considering comping the two? Do you see any similarities, differences, anything else other than what you mentioned where Upstart just grew like crazy and crashed and burned? But is there anything else people should be thinking about comparing this to a little bit buzzier or well-known [inaudible]?

Kevin: I mean, the ball case is that Pagaya isn't well known, as I said, and once it becomes more well known it'll trade up and comp with Upstart. I think that's a great bull case, I would love if that happened. I'm skeptical which is, people asked me and they asked me on Twitter as well, why is this happening? I mean, upstart is a meme stock and I don't mean to say that in a disparaging way whatsoever. It has a huge net retail following. And when you have a huge retail following, it does a few things to your stock. First of all, it adds a lot of volatility to your stock because the retail investors flow their money in and out really fast. But also what it does is it adds a really large market cap flow on your stock because a lot of shares get abandoned by people who held the stock for a while, and it's gone down and it's reminding them that it's there and when it starts showing signs in life, they jump back in.

Quantitatively, best way to look at it is just to look at Stocktwits. There's 37,000 followers on Upstart versus Pagaya has something like 2,500. So it's more than a 10:1 ratio. And at the end of the day on Stocktwits, probably the first 1,500 followers are bots. So it's really more like a 20-year, 30:1 ratio. And so when good news happens on Upstart, there's a lot of people that are sharing it on and that's great for Upstart, great for Upstart investors. Upstart's also a massive battleground stock. Short interest was huge when the stock was $10. We can talk about that later on as well, which is, there's a lot of weird short stuff that's going on these days. I'm commonly a short seller and I don't understand what some of these short positions are doing and why they're doing it because it doesn't make any sense to me. But yeah, Upstart has a 30, 40 % borrow rate on something like $300 million in all stock trades. So, there's huge amounts of interest being collected there.

I think this is what often people don't give meme stocks credit for, which is, you hold a stock for the present value of its future cash flows. Its future cash flows include the borrow rate. So something like AMC not to do a huge tangent, the borrow costs that the people have incurred for shorting AMC is basically at or above its market cap at this point in time. So the idea of Mark, AMC shouldn't trade at $6, it's an irrationally high price, it's actually not. It's actually, if you held the stock for the last year, even if the stock went bankrupt in the next four months, you end up not losing a ton of money kind of thing.

And the same thing with Upstart. You've got hundreds of sharp positions and once again comparing to Pagaya which has a tiny short position at the high borrow rate, Upstart has a huge sharp position and a huge borrow rate. And that's important. So, sorry, taking a couple of quick steps back. Upstart, hopefully Pagaya trades this in multiples as said. I don't think that's the case. I don't think many people would do the long short from a fundamentals perspective. Right now, Pagaya's numbers look way better than Upstart's. You could argue that Upstart's business model may be superior for certain reasons or maybe worse. I would generally say that at the very least, they're the same. I don't think Upstart has a big edge. I'd like to see Pagaya trade up to Upstart or at least I'd like to see Pagaya's trade up on its own merits regardless of what Upstart's doing.

Andrew: I've got a bunch of companies where I look at them like it trades for a third of the competitor. I think it's better than a competitor. And as you said, I'd love to see a trade [inaudible]. Let me add something else. So they've got a slide in their deck and this is slide 33. I don't know if you've got it on up or not. [crosstalk]

Kevin: Okay. I don't have one quite right now.

Andrew: For anyone who's listening, slide 33 is in their Q1 23 deck. And what it basically shows is for the past two years, their performance has been better than whatever the market benchmark. Their 30-day plus delinquency has been performing better than the market benchmark. And I would say like that's actually, and I don't know what the benchmark is, but I would guess that's actually really good, not just because hey, we're better than the market benchmark, but I would guess the market benchmark has some bias where again, the thing I was skeptical of, Ally's turning a loan down, how are you funding it? Like Pagaya is actually getting the loans other people wouldn't fund and they're performing with better performance than the market benchmark. So that's a point in their favor. I guess my question is, they say, hey, we do, I think it's like 30 basis points better in delinquencies over this period than the market benchmark. Is 30 base points in improved delinquencies? Is that enough to fund this business? Does that make sense?

Kevin: Yeah. I know what you're saying, which is, are they sharp enough to have enough money to give extra money to their investors and keep money enough for themselves? To make it all make sense, right?

Andrew: And fund all the overhead. Exactly.

Kevin: Yeah, I think that maps out basically that three or 4% contribution margin that they're saying. So they're saying that if we pull an extra billion dollars in revenues, the net fees less production costs is three or 4%. So ultimately, my answer is yes, I do think it does. There I agree. I love this chart. I don't use it specifically too much because of what you're saying, which is, charts, you get to pick your own benchmark, all that kind of stuff. I think that this is legit. I do. But you still have that world where there's something under the waters that the company's not disclosing or that they're not aware of or that we're not aware of that that ultimately hurts us.

But yeah, the numbers are explicitly saying that they are doing a better job with their underwriting and that there is enough. As in, there is positively better right now covering all their fixed costs. And also I think one thing to say is that their investors are buying their ABS up head over heels for this stuff. They're not having any problems funding this stuff. They come to them and say, hey, we want to deploy more. And if I'm an ABS investor, I'm probably going to be pretty sharp looking at Pagaya and say, hey, is this machine making the loans proper because I'm the one that's actually taking on the balance sheet risk? And the answer to that is they are and that's a funny thing, which is that it's weird that the, oh, I'll say weird, the debt investors and the ABS investors, arguably, if they believe that the AI is great, what are you doing buying here? Paying the ABS and taking your 10% yield, you might as well pick up the stock and pick up a double or a triple kind of thing because the two of them should be correlated in terms of their performance.

Andrew: No. Look, it is interesting because as you said, the ABS investors are funding it and they've got stuff in their deck that shows how oversubscribed their ABS is. I think they're the number one personal loans ABS two to three years in a row at this point. It is interest because if we had been talking 18 months ago, I think a question would've been, hey, are these guys a product of a zero interest rate environment? Can they really get deals done as interest rates rise? And the answer to that has been proven absolutely yes, right? 2020 was their largest ABS year ever and I think Q1 was their largest quarter ever. I can't remember specifically, but it was among them at least.

So, they definitely can do it in rising interest rates environment. The last thing for them to prove is, hey, that 2022 loan book you did, is that going to perform well enough where investors are going to come back and say, yes, this outperforms through a recession like in 2025, we're eager to give you more money? But so far the early signs are, as you're saying, yes, because the ABS investors are signing up for again and again and again and they don't appear to have a problem funding the ABS loans.

Kevin: Yep, and that's exactly. So I think it goes back to, most of what we've said before, maybe other than the offering, all of the numbers paint a great story, but you're still like, I'm skeptical. I don't know. Like, it doesn't pass a sniff test to me. Is that a fair calculation of what you cannot understand?[crosstalk]

Andrew: Yeah. I really focus on the auto loans and let's put those aside. Like even something like Klarna or these buy now, pay later that they're doing, they're getting the rejects from Klarna and the buy now, pay laters. And I just look at it and say, how can these Klarma and them are? Those are founded later than Pagaya was, right? Like, these are newer companies, they're allegedly completely data and tech-focused and just look at them and say, how can Pagaya have a consistent ability to fund loans that these guys can't? Because I don't believe there's any data mode that Pagaya could have that these guys don't have or something. So I just look at that and am skeptical. But you know, as you're saying, the proof is in the numbers and also everything is risk-adjusted, right? Like if the stock was $20 per share, it would be a much different story than, hey, the stock right now is trading for a 30% premium to liquidation value, as you said. [crosstalk]

Kevin: Let me apply that same logic to Upstart, which is, they are trading at $25 per share and have the same problems that our Pagaya has. [crosstalk]

Andrew: Oh yeah.

Kevin: Yeah.

Andrew: I hear you. But that would argue for a parish trade, and I don't think either of us are like at it.

Kevin: No. I'm not showing Upstart in any way shit. [crosstalk]

Andrew: I don't know, because it's so interests me, and I increasingly over time I'm just really attracted probably cuz I'm too stupid to find moats at this point, but I'm just really attracted to things with like hard asset value, balance sheet value, assets in the ground, whatever. And this has that, right? This has 75 cents per share of hard asset value against a dollar and 20 share price and all these other things as you're saying, and I love things with high implied volatility because those are the things where you can make. It's generally because people are saying, hey, this is either a three x or zero. So if you do a lot of work, you can maybe get a view one way or the other and I think there's [inaudible]. But then I look at the stock issuance and I just keep thinking like, man, it's really hard for me to believe a data advantage exists in this business.

Kevin: Sure. I don't have much to say on that side of things. I will say I share the same thing. Like I said, I met with management, but at the same time they're going to say we have AI, it's amazing. We have so many smart PhDs over in this field doing the work. I mean, the outbound interviews on Glassdoor despite how bad some of them are, most of them say at the end of the day, the actual core structure is good. Now Glassdoor interviews aren't really valuable, I will say, for many different reasons. But it is notable that they are saying, hey, I hated the company when I was working there. I got fired. But you know what, they had some pretty sharp tech there.

Quick pivot cause we're running out of time, but someone asked about Darwin and that recent acquisition. And also I want to give a bit more characterization, like although they do auto loans, I would say personal loans are a much bigger portion of their world in the auto loan business. And this goes down to like some communication, which is myself included. I had to dig to really get more data on this. Recently I got a list of all their ABSs and so you can kind of see their ABS issuances and how big they are, and that's effectively how they're deploying. And what I would think, I don't think many or any investors know that in the single-family rental space they did $250 million last August.

So they raised 250 million worth of investment capital from investors last August to deploy into single-family residences. So ultimately what they did was they went and spent that money buying up a whole bunch of houses in America on behalf of the investors. The capital appreciation of those houses up or down goes to the original investors, so they don't have any exposure there. However, they are applying their AI in selecting those houses. What they're saying is we have a huge, huge set of data on all of these loans. We know which people are paying back, which people aren't, and so we can, for example, pick zip codes where hey, look, turns out that these people in this zip code are suddenly paying back more likely than they normally would because that is an area that is up and coming, it's gentrifying or whatever, right?

So they're using the AI to help pick these houses on behalf of the investors, hopefully within the attentive, giving them capital return. But more importantly, once you have one of these houses, you want to manage it and get yield. And so they manage these houses on behalf of these investors and collect rents for them and they collect fees on that whole process. Now, historically, with these $250 million of homes, you have individual renters that are needing to A, send their monthly checks in, and B, fill out forms to say I need a plumber to come fix something, or C, all this prop tech stuff, right? And Pagaya used a smattering of third-party vendors that were outsourced in order to put that together. Darwin brings it all home into a single thing. So instead of paying millions of dollars of fees to all of these different platforms that manage their single-family home, single-family rental business, Darwin brings it all in-house.

Darwin is apparently, I haven't looked at detail, best in class at what they do. And so now Pagaya has its own proprietary platform where if you end up renting a house through Pagaya, which you don't know is through Pagaya, but if you rent a house through this platform, everything is sort of one stop shop there. Which ultimately leads to in theory, Pagaya is able to pick better renters because they're able to look at your creditworthiness in a different way because of the AI. And once you're using this platform, you treat the house better. And your asset value, the bare asset value in that rental business is very different than the car business and very different than a personal loan, which obviously is unsecured. So if you are an investor and you want to buy residential real estate and collect yield on it, you want to pick someone who is A, being thoughtful about what they're buying. Then you want someone who is also very good at managing it and see who's good at picking the right tenants to take on the place, and Pakaya is trying to do that. It's not a big part of their business, but it's not trivial. As I said, the $250 million was last, 250 million was last year, 350 million was the year before that. This year in August, they'll probably do another one of these deals.

Andrew: I was misunderstanding what the single-family home rental. I thought they were just doing personal loans to people who they were partnering with Blackstone single-family rental unit and doing personal loans to the renters there, but they're obviously the second. It sounds great, but it comes back to like everything you're saying has been death for any equity investor who tried to do it, right? Like, this is one of the open door arguments. Now they tried to buy not to do rentals, but right they were like, hey, we're going to apply AI to buy homes sharper. And single-family rental homes, there's a reason so many big people have struggled with it because it is very much a local market game, you need boots on the ground, as you said, like all this sort of stuff, and you just look at Pagaya like, hey, we're YOLOing in here and we're going to do it. It does sound great, but it also sounds like, hey, I've seen this story before and it ends in death like every time.

Kevin: Sure. So, at the end of the day, this single-family home business it's a small one. They're putting their toe into it. They don't have balance sheet risk on it. So if they buy every house by mistake at the wrong price, cause the algorithms don't work like some of the competitors, that's not going to be left with them holding the bag. And yeah, I could see this either being a really big business in the next five years, or I could see it shutting down. And so I look at it as aside from management distraction, which is non-trivial, I see it as a good sort of free upside thing. And they're really trying to say, we have all this data and we're applying this to these spaces that are tangential, that makes sense, which is, the consumer. We in theory have a good view on the consumer. We know what the consumer can and can't afford. We can pick good consumers and be a full-fledged offering for those people.

Andrew: Two more quick questions before we wrap this up. Number one, just Oak HC who just did the $75 million in crafts at a dollar 20 that will convert to common, do you have any thoughts on them and their investment in Pagaya?

Kevin: Yeah, I talked to Matt Weisberg there. He's the guy who runs their investment. I mean, they started in the B round and they've come back to the trough multiple times, participating in multiple rounds. Coming back here right now with this $75 million recently, he's at his favorite investment and he's made quite a few of them. And every VC says this is my favorite investment. But I mean, he has putting the money behind it himself. They did recently raise a new fund and so probably allocating out of that fund. But that's also one of those exposure things. I don't honestly have the highest regard to most VCs that I've spoken with, and I wasn't expecting a ton from Matt. Matt really knows his stuff. He's really, really, really sharp in terms of knowing how FinTech works, how all the rails work, how all the connections work. I'm trying to furiously keep up with some of the stuff he's talking about taking notes and I'm understanding maybe 25% of what he's saying. I would arguably say as well, you also have an anchor investor there, which is if things are problematic or if they need more capital, there is a world where he can help or help or maybe help arrange for another round or something like that if that were to come about kind of thing.

Andrew: And just like this question. So, management here owns a decent amount of stock, right? I think each of the kind of founders own, what is it, like 120 to 170 million shares, even at a dollar per share. That's a pretty nice chunk of change. I wish I owned a hundred million shares of anything at a dollar. But just, if they see they're very bullish on the company, right? They've painted the picture, here's our path to 700 million EBITDA, all this type of stuff. Obviously, the company can't buy back shares because they are, as you said, capital intensive. Though I do think there is an argument for you should weigh the opportunity cost and everything. But what we seem like is just mass insider buying here just taking advantage of a really depressed share price?

Kevin: That's a great question. I mean, that's something that I should probably ask them. I haven't. That hasn't come up for me, but I agree with you, which is if they are really behind it, then they should put some money behind it.

Andrew: Yeah. As you said, I haven't looked through if they cashed out in the SPAC deal or not. I didn't go that far back into the background. [crosstalk]

Kevin: The SPAC deal, I'm fairly certain was almost done all proceeds directly to the company.

Andrew: That does make sense because they've got tons of cash on their balance sheet and stuff. But I just look at it and say, hey. And it's easy for me to say that, right? I don't have $150 million of exposure like that is generational changing wealth, even if it's down from a billion or something. But I look at them like saying we're betting on the company, we've got all these great things, and I'm like, it doesn't really make a lot of sense for it to be public in general, I would say at this point.

Kevin: Sure. Yeah, it's a very funny, interesting question, which is like, if I were them, I wouldn't be doing it. And it's not because of not the alpha, but it's because of concentration risk, right? But I mean from a signaling value, it would have obviously a lot of value. But anyone that holds that much wealth, concentrated in any company whether they run it or not, I think it's crazy. And all of the academic literature backs set up as well. We have a few minutes left. I'll just do a quick intro or plug about myself just so people know. I am a hedge fund manager, but at the same time I'm on a faculty at Stanford. I teach a course called Financial Trading Strategy at Stanford. That's actually my primary gig. Running my own fund is a secondary one.

What I do and how I do it is basically, I teach these live cases in my classes. And so every year I bring a new group of Stanford GSP students into the classroom. We talk about markets and then I bring up three or four or five different companies and names and explain what's going on with it. Everything I do is sort of special sit situations, so a special sits trading or investment. So we're always looking at something weird or quirky or different and then we just run through all of the gamut of how it all comes together and the pieces. And then that's what makes my course unique is because I'm one of the few who use live cases where we don't know what's going to happen. And I get emails three months, six months after students graduate being like, hey, we talked about this for a lot and now are asking to see if it'll come out versus, taking a case from 10 years ago, dusting off and talking about, oh, had you done this 10 years ago with the knowledge of hindsight or the benefit of hindsight, let's say you should have done this. Obviously, we know in the investment world it's way more.

Andrew: It's very easy. Like at every trade I make with the benefit of hindsight always works out. I just don't know why I invest in anything [crosstalk] [inaudible].

Kevin: I don't even mind [crosstalk] [inaudible].

Andrew: Look, this has been great and, you say quirky situations. I mean, we've stumbled on some pretty quirky situations together though. It is funny the quirky situations they can work out really big, but sometimes you've got to have much faster trading fingers than I have for them. And I'm sure you can think of the two I've got in mind that we've talked about offline that I don't really feel like mentioning here. Cool. But Kevin, this has been great. I really enjoyed this. I'll include a link to both who's seeking articles in the show notes so people can go see kind of written how you're thinking about the company there. Include a link to your Twitter in case anybody wants to. I mean, under a hundred followers, Kevin, my gosh, come on.

Kevin: I just started like six weeks ago, so it's one of those things. I could use some of your 30,000 or 50,000. What's the number now?

Andrew: You know, I don't like to talk about. [crosstalk] I'm sure the hundred number is going up. But look, I really appreciate it. Really appreciate coming on and looking forward to having you on again.

Kevin: All right, thanks. See you. Bye.

[END]