John Maxfield on Investing in Banks in a Post-SIVB World (episode #157)

John Maxfield, Editor of the Maxfield on Banks, has spent nearly two decades studying America's best and worst banks, the history of banking, and interviewing bank leaders. John joins the Yet Another Value Podcast to answer questions regarding investing banks, his mindset during this "crisis" and how to think about investing in banks moving forward.

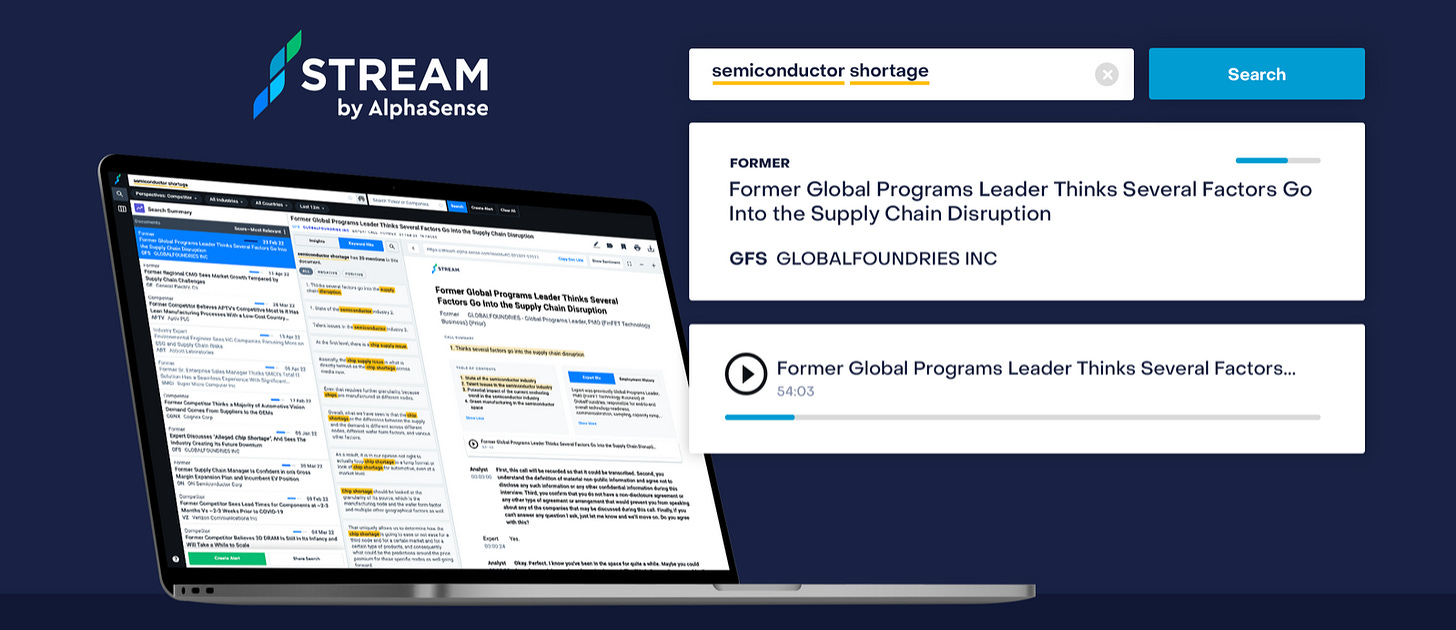

This podcast is brought to you by Stream by AlphaSense.

With Stream, you have instant access to a library of 26,000+ transcripts and one-on-one calls with former executives, customers, competitors, and channel participants. Speed up your research process with AI technology that understands your intent and sentiment to give you deeper insights. Readers and listeners can get a free trial here.

Please follow the podcast on Spotify, iTunes, or most other podcast players, as well as on YouTube if you prefer video! And please be sure to rate / review the podcast if you enjoy it, or share it with someone else who would enjoy it (more listeners is a critical part of the flywheel that keeps this Substack and podcast going!).

Disclaimer: Nothing on this podcast or on this blog is investing or financial advice; please see our full disclaimer here. The transcript below is from a third party transcription service; it’s entirely possible there are some errors in the transcript

Transcript begins below

Andrew Walker: All right. Hello and welcome to Yet Another Value Podcast. I'm your host Andrew Walker. If you'd like this podcast, it would mean a lot if you could rate, subscribe, review it wherever you're watching or listening to it. With me today, I'm happy to have on John Maxfield. John is the founder of the recently launched Maxfield on Banks. It's a new Substack. I'll include a link in the show notes. I'll let John go through his fuller, more wholesome background in a second. But just before we get there, let's start the podcast the way I do every podcast. A quick disclaimer to remind everyone, nothing on this podcast is investing advice. Neither of us are financial advisors, please consult one. Do your own work. We're going to be talking about a lot of bank stocks today. It feels like bank stocks are riskier than pre-revenue biotech startups these days. Consider that, I guess, extra degree of risk. But all that out the way, John, I'll just turn it over to you. Maybe to start, you've obviously launched Maxfield on Banks. Again, link in the show notes. You've got a lot of background in the banking sector, which I think makes you the perfect person to come on and talk today about banks in general. But maybe just real quickly, you could give a little bit of your background, so listeners know what your perspective and what they're hearing from.

John Maxfield: Yeah, sure. Appreciate the invitation to come on, Andrew. I think the best way to characterize me is I'm a student of banking. I just study it, I study it really intensely. In my head, I keep thinking that financial crisis is 10 years ago, but the financial crisis was actually what? 15 years ago. I need to start adjusting that I've been studying it for 15 years. When you study a subject, you go through different aspects of it. You start with, I think, in banking, that you're tempted to go start with the analytical stuff, because it's the most concrete. That's funny because at the end of the curve, you realize that's the least concrete, but that's neither here nor there. I did all that. I started writing for an organization called The Motley Fool. I'm sure some of your readers are familiar with the Motley Fool. Then I went and was the editor in chief of a banking magazine. Then I've been running an organization for the family of a very well-known banker guy by the name of Robert Wilmers, who ran M&T Bank from 1983 until 2002. He passed away in 2017. Bob Wilmers, he is this legend in banking. If you take every single bank in the United States and you rank them by total all times shareholder return, Bob was either number one or number two. He went back and forth with this guy named Mick Blodnick of Glacier BanCorp. I've done all that stuff.

But really, what I've been doing throughout the years at all these different positions is just continuing to cumulatively add what I know about banking on top of it. I start with the analytical stuff, then I've spent a lot of time developing relationships with bankers across the country and spending time with them, family members or friends or colleagues. Then just in the past two years and throughout all of this, I would read. I've been reading history and trying to get the full picture of this thing in my head. In the past few years, I really doubled down and consolidated on that history part. At this point, Charlie Munger talks about mental models. I guess this would be a mental model, but I have a pretty comprehensive model of banking in my head that is just pieces of the greatest bankers that I've been able to talk to throughout time. All the electrical research, I've done all the stuff I've read about banking going back to the very beginning. All that stuff put into one thing. That's what I've been spending my time with.

Andrew: That's great. You did an interview over the weekend. You were talking about the history of banking chipping in back in the 17th and early 1800s to save cities and stuff and I was like, wow, that is some interesting historical perspective. But I guess let's just jump right into it. You and I are talking on Monday, March 28th. Over the weekend, you get UBS and CS merging. FRC, First Republic is in the news every day. I think in the interview, you were like, "Look, now is the time a lot of these regional banks are trading at 50% of the book." You're saying, "If you just take a historical perspective, now is the time that you want to be sharpening your pencils or buying into banks." That is the time when they trade at these levels. I do think people would push back in two ways. They would say, "Hey, Silvergate, Silicon Valley, all these banks, and we can talk what happens then. All of them were trading for half of tangible book the moment before regulators stepped in and seized them and the shareholders are obviously going to get zero there. Or B, FRC, as you are talking stocks probably at 20, I think last I checked book was 70. They earned $10 per share last year or something. I got this specific number somewhere, I can pull up. But people say, "Okay, yeah, but that's mark to market book." But that's not mark to market book, right? That's fantasy book where they're loans and held to maturity securities. I think they would have way underwater book value if they did it. I threw so much at you. I'll just pause there, what are your overall thoughts on investing in banks right now?

John: The thing to know about buying and owning bank stocks, is that a really good bank will earn 12 to 14% on his equity every year. Just bang, bang, bang every single year. That is a really good return compounded over many years, right? Because that's you're doubling every what? Five years, right?

Andrew: The S&P historically it's what? About 8%, right? If you're getting 12%, you're getting 50% more doesn't sound a lot in maybe one year. But as you said, you compound that over 10 years and it's absolutely enormous wealth creation.

John: You double every six years, right? But here's the problem with that number. 12% compounded is a really good number. You tell anybody 12% in any given year and they're like, "Well, that's nothing to write home about." The problem with bank stocks is that, you're just not going to get that ridiculous growth, that you're going to get your tech stocks that shoots off or anything like that. What that means is that if you really want to juice those returns, the price that you pay for the stock really matters, right? Because you're up against a fixed return schedule. Really what you want, this is how I approach it, okay? The way I buy bank stocks and the way that a lot of folks in my realm buy back stocks, is that you don't buy bank stocks for a long time and then you buy a lot of bank stocks at one time. That one time you by them is when the world seems to be going to hell. That's what's going on right now. How do you know the world is going to hell? You know it because everybody's afraid, right? It's not something that you can quantify, right? It's not some tangible thing but you can just feel it. You can see it and you can feel it. You know, Andrew.

Andrew: No, I was just going to say, I hear you and you can't 100% quantify but you can look at the VIX. VIX was screaming higher last week. I hear you at the time to buy, but it's very scary when you have Silvergate, Silicon Valley, and Signature Bank within a week. That's three pretty sizable banks just taken over, shut down, unwound in a week. Then you've got First Republic, which maybe not the gold standard, but I don't know anybody who would have said, "That's a bad bank over there." You've got them, it seems like, on death's door every day. As you said, the time to buy is when there's blood in the streets. But whoo, is it scary when there's blood in the streets in the banking market versus when there's the blood in the streets in the oil markets or something.

John: I don't know, though. I mean, and you go back to the oil crisis in the 80s. You go back to the tech bubble. I mean, it's brutal when you go through these things. But here's the thing. You mentioned Silvergate. You mentioned Silicon Valley. You mentioned First Republic and Signatures. If you look at each one of those banks, these are not ordinary banks, right? Silvergate really was hardly even a bank, right? It's more of an exchange, right? Just move that one out. That's always been an outlier. Get that out of the way. Now we go to Silicon Valley. What was the deal at Silicon Valley? Well, it too was this very unusual situation, where you had all of this liquidity flood into the system after the pandemic begins. Where does that liquidity go? That liquidity goes in large part, the tip of that spear is the tech VC market, right? Remember, the IPOs just exploded at the time.

In fact, a good friend of mine used to work at a company called Encino. I can't remember. I think they were pricing it at 25 bucks a share the night before. They raised it to 40 bucks a share. It came out in 75. I mean, it was just crazy. You had all this money flooding with all the bunch of that money collected in Silicon Valley Bank because that's who that bank serves. It's at the very tip of this liquidity spear, right? The one thing we know about liquidity is that, when there's a huge surge of liquidity into the system, it never just quietly exits out the side door, it bangs its way out the front. That is what it's doing right now. This is not the only time that we're banging throughout the front because that's a huge liquidity surge. But this is one of the times that it is doing that. Then you move to Signature. What was the situation with Signature? Well, Signature had a variety of things going on there. One of which was they got deep into cryptos.

Andrew: Signature was almost the hybrid of Silicon Valley Bank and Silvergate, where they had extreme exposure to New York City commercial real estate, and they had exposure to crypto plays. They were that nice little double whammy.

John: That's right. Then if you go back even further in time, they took a whole bunch of losses on the medallions. When Uber and Lyft came out and then caused taxi medallions to tank, well, there was Signature. They've always had the reputation of flaunting the regulators. I've talked to bankers, the CEOs of major banks who think that it was the sacrificial lamb. They're like, "Well, we needed another one to go and these guys deserve to go because they [crosstalk]"

Andrew: Barney Frank would certainly agree with you that it was the sacrificial lamb.

John: Yes, he would certainly, which is another irony in all of this, because he was on the board. Then you take these ones and then First Republic. Now you're moving more over into your normal type of bank. But even First Republic has some unique characteristics, right? You're concentrated in one customer class. For all intents and purposes, I guess, really the wealthy and then business. You're concentrated in those two things. As a consequence of those concentrations, what do you see? You see that you're, what is the number? I think 80% of their deposits were uninsured. You think about that, you think like, "Well, like, what was it at Silicon Valley?" I think at Silicon Valley it's 95% were uninsured. What was it at Signature? I think it was 94% were uninsured or something like that. What's going on right now is a run on banks with uninsured deposits. That's just what that was going on there with. With these other catalysts sparked it, whether it was crypto or the drawdown in the tech IPO market. You go to your traditional regional bank, it's just a different story. [crosstalk]

Andrew: Can I just ask a silly question here, right? Silicon Valley Bank, there were stories of people with 100 million, a billion. I believe Circle had upwards of $5 billion in uninsured deposits. They managed to bring it down to 3 billion before the bank was taken over. But when I see these massive deposits, I do think because you can just go and sweep it into a money market account, right? Then it's no longer an uninsured deposit. You're basically investing in government T-Bills or something like it. Why are customers with 10, 20, 50, 100 million, why are they running 100-million-dollar uninsured deposits in First Republic?

John: Well, I mean, sometimes you just need total and complete liquidity. I mean, you don't want any risk, you don't want to be tied to anything, whatever. Also, sometimes you're in the middle of a transaction, right? You'll park some money here, 100 million dollars here because you didn't complete a transaction. That's the thing that will happen, too. But I mean, there's a [crosstalk]

Andrew: Maybe I've just never been a CFO managing a multi-billion-dollar organization and also, maybe just because I was looking at Circle and be like, "You had 5 billion in an uninsured account?" That was just one of the things that jumps out at me. That does take me to another risk and we'll come back to this. But the regional banks, a lot of them are based on and for years, the thesis has been as interest rates rise, they have all these deposits. They're going to be low-cost, sticky deposits. Interest rates rise, their net interest margins are going to expose. I hear you that a lot of these regional banks have a much more diversified deposit basis. A lot more of them are insured, so there's no risk of them. But is this going to cause, going forward, banks across the board are going to have lower ROE's because people, they're going to be a little bit more careful with their deposits, right? They're going to say, "I can't keep $2 million uninsured here. Let's just do what I was saying earlier and sweep it into a money market." Or even if you've got an insured deposit, maybe you're looking at it and say, "I get 0% interest on the insured deposit." This has caused people to think a little bit that I can go sweep it into a money market or park it in a two-month treasury and get some interest. Is this going to affect the go forward earnings of all these banks, ignoring the risk and everything of immediate blow up?

John: Well, I mean, when you're talking about the deposits in excess of the insurance limit, I mean, but really there's a lot that at any individual bank, that's not the lion's share of deposits. First of all, that's a good thing to keep in mind, other than these outlier situations. The other thing to keep in mind is that there are products, what this will probably do, my guess, is that there are products like Gene Ludwig's company that sold at IBM few years ago, somebody brings $10 million into a bank. Well, this company will take that and they'll go 250 here, 250 here.

Andrew: One of my friends runs a FinTech that does that apparently.

John: The system has ways of spreading that. If anything, it will raise the awareness about that type of thing. But here's the irony, Andrew, is that this won't be the problem next time. This is like fighting the last war. We will fight the last war, but that won't be the next war.

Andrew: Hey, if you look at all the regulations around even FRC, these guys, the worry was not interest rates rising, mark to market, the worry with still, hey, are they going to be suffering? Are there assets that are marked at their book at 100 or 90 that are actually going to be worth zero back in the financial crisis? What I'm hearing from you is, if I'm looking at a regional bank and one of my concerns is, hey, I was hoping they would be able to do that 12 to 15% that we were talking about over a normalized cycle, I'm worried that's going to come down because they're going to have to pay more for deposits. People are going to be sweeping a lot of their deposits. You don't think longer term, that's going to be a concern?

John: Everything adjusts. The other thing to keep in mind is that we've been through nine major banking crises in the US history. We've been through many more minor crises or probably, I don't know, as many as two dozen crises total, when you can put both minor and major ones together. You know what always happens? It always goes back to just the way it was. It always does.

Andrew: I've had a lot of people who've been like, "Hey, why don't we end up with the Canadian model, which is just four big banks in Canada basically control everything. Why aren't we, JP Morgan, Citi, B of A, and choose one other major bank? Why don't we end up with four or five? I was like, "Well, that's just not how the US works, right?" We've had regional and community banks for hundreds of years. I don't think we're going to have a wholesale change. If they did try to regulate that away, I think there would be a lot of political pushback, because these guys are major players in the local communities.

John: What you have to ask yourself is, are there structural reasons that we have that many banks in others countries don't? There are historical reasons, but there are also structural reasons. What are those structural reasons? Well, you go and you look at a map, where are all of these banks concentrated? They're concentrated in Iowa, Illinois, Missouri, Minnesota, Ohio. These are ag states. If you're flying over an ag state and you look down, there's all these little crop circles and stuff like that. Well, those are individual farms. Farm lending is incredibly bespoke. Maybe FinTech will someday conquer that, but it ain't close yet. What you have is you have all these local lenders on the ground that have to know the farmer, the land, his equipment, all these different components that you can't fit into a model cleanly. When you think about why we have so many banks is because we have the best damn land in the whole world. I mean, we have the best land in the whole world. Just looking at where our country sits on the globe, it's a pretty good deal.

The extent to which the banking industry will consolidate will be a function of, in my opinion, the extent to which the agricultural industry consolidates. Because if the agricultural industry moves all the way down and gets rid of all these individual farms, then the industry itself will be spreading the risk. You won't need banks to spread the risk and know the risk and thereby spread it. That's really will be the thing. Let me bring one more point about this. If you have in your mind the chart of the bank population in the United States going all the way back to, let's say, 1800, it looks like it's going along the bottom axis. Then it tips up. It starts tipping up in around 1870s. It goes way high and it peaks in 1921. Then tears down in 1930s, when you have all those failures in the Great Depression.

Andrew: I think I can imagine what [inaudible]

John: Right. Then you have a long period where it's flat that's called Great Moderation. Then a little tail and then consolidation ever since. You have these basically a big surge in the number of these things. You say, "Well, what caused that surge? Why are there so many of these things?" The reason there were so many of these things is because disposable income was born in United States. When disposable income came about, you had all of these deposits from all of these people. You have these banks that are talking like, "Oh, my god, look at how much fucking money there is." You have all these banks that are opening up and starting up and opening up and starting up. Ever since then we've been working backwards from that to, I guess, if there's some natural equilibrium number of banks per capita or something like that, we've been working back from that ever since 1921.

Andrew: Look, obviously, I hear you with there's blood in the streets, now's the time to buy. But I do look and I was just looking at some of these over the weekend, right? What is it? Western Alliance. Their stock is, as you and I were talking, in the low 30s. Tangible book at the end of 2022 was $40 per share. They earned $10 per share in 2022. I'm rounding up a little bit. You're talking about buying it three times 2022's earnings, approaching 80% of tangible book. Those seem great. But then I guess I look at two things. I look at the bank runs that are happening. I'm like, "Hey, are they going to lose funding?" It seems like it happened to Western Alliance, it happened in Silicon Valley, it could happen there. That's A. Then B, I look at their loans on their books. If I remember my numbers correctly, they had $51 billion of loans at the end of 2022. If you fair valued the loans, I think it was about 47 or 48 billion. That's about a three or $4 billion difference. Guess what? That wipes out almost all of that tangible book. I'm just using one example. We could have chose Pacific West Coast Alliance or whatever. We could have chose several of them and the numbers look similar. But I look at them and say, "They look very cheap if I'm looking historically. But I'm worried about run and I'm worried about that mark to market of the book." How do you think investors should be weighing those risks?

John: I mean, I think that they should just chill out, to be honest with you. You don't need the mark to market loan book. Why mark to market loan book?

Andrew: But doesn't that sound the same as you don't need to mark to market, you're held to maturity treasury securities?

John: We're in this period of just irrational fear is where we're at right now. If you take a step back and you say, "Okay, let's think about this," there's a reason they don't mark to market held to maturity securities, right? What's the reason? The reason is because they just let those things naturally roll off when they mature. They get poor value when that happens, right? So long as there isn't this fear, where this causes a liquidity run, then you don't have an issue, right? But it's just only in this context that we think that this is a problem. I mean, when your interest rates go up as fast and as far as they have, and they've never gone up this far fast in history. I mean, I guess, theoretically, you could mark everything to market and then all the banks would be insolvent. But that's stupid. It's just like why? Let the loans pay off. They get them apart and everybody's good. Everybody's whole. I understand the argument. But I also don't understand the argument. Because humans, they want to find something. They want to find something to be a problem. They want to find that it sounds smart to be the person who identifies this problem. They want to be contrarian and all this stuff. Sometimes when you step back and look at it, you're just like, it's not complicated. This is simple stuff. You don't need to mark to market loans. There's just nobody's going to do that. Unless you're going to liquidate that bank and sell those loans. In that case, you're not only marking them to market. What happens is you got to mark those things way down. Because you have the FDIC liquidating them and the FDIC doesn't care. They'll just sell it for whatever.

Andrew: I 100%. hear you, right? Hey, these loans are probably going to be money good when they're made whole. If the deposit base just stays there, everything's going to be fine. But on the other hand, I mean, life insurers do the same thing, right? Life insurers can hold things to market. But life insurers, they're buying 30-year bonds against the 30-year payout of a life insurance policy, right? Their assets are much more marked with their liabilities where, as you're saying, and you're the one who had the confidence is king post, which I really enjoyed recently. I think that was your first or second post. But you're just saying, "Hey, you need to have confidence in these banks that they're going to be there and then the loans will pay off at par." But it does sound silly to go and say "Hey, just pretend that all these loans, you made a 4% and interest rates of government securities yielding 5%." Just pretend those loans are going to be made whole because it sounds very similar to, "Hey, these loans that you've got marked on your book at costs, let's just pretend they're worth costs, even though they're going to $0. It just sounds crazy to have that trust when they're on a mark to market basis, they're zeroed.

John: I mean, when you think about it, the banking system isn't a function of banking. The banking system, how its structured, is a function of our priorities and society and what matters to us. You have fractional reserve lending. You have the accounting rules. But what are all of these? These are all driven towards facilitating economic growth in the United States. Economic growth is the thing that facilitates our power. It's the thing that allows us to be the global policeman and to finance that. Whereas, Canada's got four banks. They don't have as many provinces as we do and they have universal health care and all these different things. Well, the reason they have is because we're protecting their southern border and they haven't got any other borders. This is a product of the decisions that this country has made over the years. It's in times like this, we look at it and think like, yeah, they can be better. But it's an all the other times, which are the eight years out of the 10, that everyone's like, "This works really well." Because the other thing to keep in mind is that, I mean, the reason you have these expansions and contractions is because of too much credit. Then you got to get dropped back. Too much credit, got dropped back. It's always mistakes are driving these things. But let's go back to 1873. 1873 was a major panic in this country. That panic then lead into they call it the Long Depression. That was a bad depression, 1857, Long Depression. 1893, same thing. Then the Great Depression. Those are the four major depressions in US history.

What happened in 1873? What was the catalyst that caused that that crisis? It was you had this company called J. Cook and Company. J. Cook and Company, this was the guy who basically sold all the bonds in the Civil War. It was Grant, I can't remember if it's Appomattox or after the one of those major battles. It's something the fact that if we didn't have J. Cook, the Union would not have won the war. J. Cook is selling all these bonds to finance the war. Nobody thought it can be done. Then they do that and then he gets in real tight with the government. The Cook family are really good people. They get down with the government. Then the government comes to J. Cook and says, "Hey, we're trying to shore up our northern border against the British who are trying to come down, right? We think that one way to shore that up is you want to populate that area." The best way to populate that area is what? To build a railroad. They have the Northern Pacific. Well, the Northern Pacific is having problems getting financing. Because you have these railroad booms and busts back at the time. They can just go to J. Cook, who can finance anything. They're like, "Can you find Northern Pacific?" He's like, "What the heck? Sure. Absolutely." He finances it. Well, he gets caught with all that stuff on their books right when the market takes a turn. His bank fails, there's all these runs, it causes all this stuff like the stuff we're seeing right now, but times 10, right? Then you have this Long Depression. Then you have to step back and you have to say, "Are crises worth it or are crises not worth it?" That's the question, right? Are crises worth it or are crises not worth it?" We built the Northern Pacific Railroad. That helped short the lines against the British. Where I live, Oregon and the state right above me, Washington is ours, not the Brits.

Andrew: Look, in the 1800s, we built the Northern Pacific Railroad. In the 2020s, I could get ice cream delivered to my door in six minutes. I mean, look at the banking system funding all of this innovative growth. I definitely do hear you there. Let me just ask in a different way. Silicon Valley Bank, I can't remember the exact things but I think they had 45% of their deposits were pulled in a day when the thing. That meant the regulator's just had to step in, right? I do wonder, in the 30s, you had to go to a bank where everybody would be panicking. But you literally had to go to the bank, wait in a line, and withdraw all your cash, right? It would be not that a withdrawal and in a run is ever orderly, but it would be a little more orderly. Whereas now, you and I right now, we could start on this podcast a rumor that XYZ Bank, I hope there's no XYZ Bank that I'm starting, but we can start the rumor XYZ, and I'll throw A in there. XYZA Bank is going to have a run. Everybody should get out now. You panic. If we were successful, I mean, this is what happened with Silicon Valley Bank. 100% with a keystroke, somebody could do it and all the deposits could be gone in a day. I guess what I'm wondering is, is your model where everybody just needs to chill, I completely get that. But is that model more a pre-internet model? Whereas today, banks are just more prone to runs and because of that, they need to run with a lot more liquidity, their books maybe should be marked a little bit more aggressively to fair value accounting, just because if they're not, they're more prone to liquidity runs.

John: Just to clarify, my model isn't that you should just chill but that's just what I have [crosstalk]

Andrew: No, you were saying that the confidence the loans will pay off. But I keep thinking Silicon Valley Bank, those were 30-year treasuries. Those would have paid off. If nobody had pulled they would have been completely fine. We probably wouldn't be having this podcast taping right now.

John: You just have to recognize that there are periods in time, where all the real rules go off the table. Then it's just as the lizard brain is driving everything. We're in a period where lizard brain is driving everything. It's fight or flight. There's this huge, all that behavioral finance stuff that's all about this. If you're a bank, if you fail and to a certain extent, whether even if you and I started rumor about XYZ Bank and XYZ Bank failed and it would be our fault, it would also be XYZ Bank's fault, right? Because you need to build a bank that can survive that, because that has been the case since the beginning of time. You've had these rumors bring down banks and all this irrational fear. There's always going to be a crisis. There's always going to be a crisis and you have to be prepared for that. I would say that, but to talk about your point about the nature of these runs and how that has evolved, the first time we really saw that was in 1984 with the failure of Continental Illinois, which was the sixth biggest bank in the country at the time, a big wholesale bank based up in Chicago.

It had exposure to the small bank in Oklahoma called Penn Square Bank, and been buying all these loan participations that Penn Square Bank was selling out of the energy at the Permian Basin. They're the largest purchaser of those. Well, if you look, what's crazy about Continental Illinois is that if you look at their earnings, it never lost money. Their earnings went down but it earned money every single year. What that tells us is that and then the federal government or the FDIC came in and seized it in 1984 because they had a huge run on their deposits. Where did that run their deposits come from? Big wholesale depositors, principally overseas. That just happened all at once. If you are really concerned about this stuff, what you do and you want to buy into the sector, you can go to the FDIC website and type in "BankFind Suite". You can go to the BankFind Suite and it has all the data of every single bank in the United States, public and private. Then you can start playing around with the statistics and you can say, one of the stats that they track is the percent of deposits insured. You can go in and you can get the percents. Then go find a traditional bank with a high percentage of deposits insured. If you want to invest and you're afraid of these types of things, that's the direction that I was going.

Andrew: It's just crazy because I am absolutely no bank expert, but I've been following and we've invested in them in the past. I've never heard of the percent of deposit insured stat before. I probably looked at 30 bank earnings reports in the past week, just looking through this up. I don't know a single company that reported percent of banks insured deposits. Now it seems to be the most important thing that's everyone's talking about. I bet you, next earnings, we're going to see a lot of them. But it's just crazy how quickly stats can evolve in something that I'm sure only banking, I'm going to use the term nicely, nerds like yourself would really think about all of a sudden, it's the most important thing in the world.

John: It's funny to say that because a good friend of mine runs one of the larger bank hedge funds, a bank focused hedge funds. We were talking about this the other day and holding all else equal before all this happened. You had two banks that were identical. But for the percent of deposits insured, would you at that point, before all this stuff got into our brains and change how we thought about all this, would you characterize that bank being riskier than the other bank?

Andrew: You probably would have and before this, I would guess, you would have gone more towards the bank with lower percent of deposits insured, because you would have thought, "That bank, they're doing really great with business clients." You would have looked at that as a relationship metric that they're going to have more growth opportunities, loan opportunities, everything in the future. It's just funny how that would change quickly.

John: Because you bring up a good point. You could read that statistic two ways. You could say that's riskier, because if you were insured, where we could say, "Well, the most sophisticated depositors believe in this bank," so it's just one of those things to your point. This is the shiny object on the beach at the moment. That's what everybody's going after.

Andrew: You would have thought to yourself, "This bank has the potential to be the next First Republic, which trades for two X book. Everybody thinks they're the gold standard of banking." Just sticking on First Republic, I do have a question, right? I think it's pretty clear whether you think the $30 billion in deposits they got last week are enough or not, I think it's the word "bailout" or something, that gets pretty clear that there's been a lot of franchise risk there. You don't have to use First Republic as a specific example. But these banks, once they get to the news as desperate, how do you think about the franchise value evaporating or their thought process for bailouts? Because if I just took it from one bank and one bank specifically to all banks in general, I know a lot of people have just said, "Hey, the government has been behind the curve and you need to come in all at once and just stop the run in its tracks. They've been well behind there. All of these banks have been well behind." Hey, the answer is not getting 30 billion deposits. The answer is if you're about to put out a liquidity press release, you do it alongside, hey, we also just raised $50 billion in equity or something.

John: I mean, let me start by saying that First Republic is a really good bank. I mean, it's almost unbelievable that this thing, it's going through what it's going through, right?

Andrew: I had multiple people emailing like, "I've never had customer service like First Republic gives me. I love it. I can't imagine leaving them." I'm like, "Look, I get you. But at the same time, once the run starts and you look at their balance sheet, you wonder how the heck they're going to be able to do this."

John: I mean, I read was that they lost 70 billion in a day or something like that, 71 billion in a day. Then 30 billion came in from this private sector bailout or I don't know what you call it. Is that enough? I don't know, I haven't examined their balance sheet closely enough to pine on that particular question. But I will tell you, to your point about franchise risk, I mean, somebody my perspective, you don't want to feed into this stuff because people are like, "John knows about this stuff." You don't want to feed into it. But I'll say, taking it out of the context of First Republic, I mean, it certainly could survive. All right. Particularly if these big banks have its back and make sure that it's got enough liquidity, it could certainly survive. But from an investment perspective, is that thing going to ever be worth what it was before? I mean, are those deposits going to come all flooding back in from Chase and stuff like that? I don't know. I would be skeptical that that would be the case.

Andrew: It's not just that. It's also, if you were a business, small business, large business, whatever, FRC's whole thing was A, yes, they're going to make money on net interest margin. But they were going to make money by having your revolver or whatever. If you're a business now and your revolver was at FRC, it would be literal mismanagement to not go and shop somewhere else. Because FRC can C, shut down whatever it is. You don't know if your revolver is going to be there, if you need your revolver and FRC is gone. I just have to think, a month ago, they had the franchise where nobody thought about them. Now, if you're a business, I've got doctor friends who were like, "I'm under the insured limit. But I was terrified that FDIC takes it and my deposit was frozen for two weeks and I can't make payroll." They're definitely looking elsewhere. I have to imagine there is maybe not, obviously, it's a great franchise. They got the wealth management and everything. I'm not saying the franchise is worth nothing, but it's worth a lot less than it was a month ago. Everyday that the headlines stick out there, it's going to be worth a lot less. We've talked regionals a lot, right? First Republic, Pac West, Western Alliance, all that. What if I dropped from the regionals to the much smaller guys, the community banks and that sort of stuff? What's going on now have, of course, it's going to have some impact on them. But most of that is going to be insured mom and pop deposits. Is this going to have any impact on them? Or are they just sleep at night safe banks?

John: Well, I mean, what's interesting about this is actually really a hot topic right now. Because what you have with these big banks were basically all the deposits are insured at these big banks, for all intents purposes, right? There's an implicit guarantee of the accounts.

Andrew: Yellen basically said that, right? They're not going to let JPMorgan go under. They couldn't, the economy, we'd be in a massive global depression. Everything would explode. We'd be talking about buy guns and gold and hunker down.

John: I mean, the fact that Citigroup is still here today, after 150 years of stepping in the middle of every single crisis that has occurred, is a testament to that fact.

Andrew: Credit Suisse might take issue with you saying, Citgroup is the one that steps into every crisis. But aside from that?

John: I don't know the history of Credit Suisse as well, but I mean, I can literally go back to the early 1900s and just walk through Citigroup. It's just like they lent money on sugar in Cuba, then that went south. Then they did all that stuff where just every single thing they are right in the middle of. Our little banks, this is a good question. Let me answer it this way. My wife and my family's balance sheet, about 60% of it is investment in a community bank, private. We've known these people for four generations. The family that runs this bank for four generations, we've been invested with them for four generations. I mean, it's just consistent performance. It's an ag bank, it knows the area, it knows the land, it is the dominant bank in that market. It's expanding out slowly in and around the area. It's in Nebraska. It's just 12%, 14%, 10%, just right in and around there every single year on its equity and just totally consistent. There are models. You go down and you look at Ross McKnight and it's called Interbank. I think now officially the bank itself is based in Oklahoma but the holding company is based in Texas. But it's run by this guy named Ross McKnight. These guys, this is a crazy model. They have zero securities on their balance sheet. $0 for the securities on the balance sheet. It is loans and cash. That's it. That's all that thing is.

Now you're like, "God, that's brilliant." Just because what has happened. Again, Ross's bank just every year consistent. The president at that bank is a guy named C.K, Lee, a fantastic banker. Just consistent. There's another bank up in Oklahoma that's owned by Aaron Graft. Aaron Graft is the CEO of Triumph. It's owned by Aaron Graft's father and a business partner. They went in and bought this bank in the 80s, when there was the energy crisis. They got this thing for pennies on the dollar from the FDIC. They've just been running it ever since. Now, they haven't been tacking on additional banks whenever they have the opportunity like Ross has. Ross McKnight has grown his up to 4.2 billion. They've gone much more slowly. They'd just been happy taking what they've been given. They earn a couple million bucks every year. There is a ton of promise in little banks. You can still earn great returns. But the fear in the market right now is that because of the implicit guarantee of these big banks, that puts all these small banks at a disadvantage, right? Then the rational thing to do is to take your money, if it's above the limit, take that money over into one of these big banks. But what I would say to that is that that argument has been made after every single crisis. Again, it all goes back to normal.

Andrew: There have been the calls just raise deposit insurance to just basically all deposits. Do you think the FDIC needs to do that? Are you worried about the adverse consequences of that in the long run?

John: Well, I mean, I was talking to a good buddy of mine who runs his fantastic bank. We were exchanging messages the other day about this very thing. You go back to the beginning of when the arguments around deposit insurance really started gaining momentum in the 20s. The really good bankers were like, "We don't want that. We want some differentiation. Either we're capitalists or we're not capitalist." Again, it's one of those things that you have to decide. Do you want differentiation? Or do you want everybody to be the same? That's a societal question.

Andrew: I definitely hear you. But I do think we've also come into the point where finance is so complex. Let's just go to one extreme. Do you want FDIC insure deposits at zero? I don't think anybody wants my grandma going and having to check bank whole sheets to figure out where she should park her deposit money, right? I think we've said that's not going to be the answer. If that's not the answer, having the 250,000 limit, where anything above that? Again, I look at Circle, $3 billion in deposits at Silicon Valley Bank and they couldn't read the balance sheet there. That seems a little crazy to me. But it does seem to me like once you've gone $250,000 limit for everyone, except for the giant guys have implicitly unlimited, it seems like we've just decided as a society, hey, deposits will get made whole no matter what. Let's not have this thing. It's like when I go to a grocery store and I grab a box of cereal off the shelf, I don't have to decide, hey, is there rat poison in here or not? I can decide if the sugar content's too high. But it seems like we've decided, when you go park your money to a bank, you don't have to decide, hey, am I taking risk here? It's like the zero, you're not going to get killed in it.

John: I mean, it's one of those questions like, I don't know the answer to this question. I thought about it. I just don't know. Do you have a limit or do you not have a limit? Or do we have a limit right now? I mean, maybe we don't have a limit right now.

Andrew: I think we're increasingly close to we don't, right? Because you bail Silicon Valley Bank out and there would have been a lot of crypto startups that lost a lot of money if you didn't. If you're going to bail out the crypto startups, it seems damn sure you should bail out my grandma if she loses her money.

John: But then you think about like, well, does that put us into an Ireland situation in the financial crisis? [crosstalk] come and rescue. I can't remember if it was Finland or Norway is one of the Scandinavian countries in that same situation. I mean, there's a give and a take to all of these things. It exposes you to a lot more liability from a government perspective. Hell, maybe it doesn't even matter. Maybe we have too much debt anyway. What's a little bit more on top? It's a great theoretical question. But again, it's only one that we ask in these short little periods of time, where fear is the kind of the prevailing emotion as opposed to greed.

Andrew: I read that we started this podcast off and I think the way you generally said it was, "Look, there's blood in the streets. The time to buy banks is when they're trading under tangible book value. You want to be greedy when everyone's fearful," all that type of stuff. This is not financial advice. But I know you went on Sunday Brunch and there were a couple of stocks you'd liked. I just want to ask, are there any that you think if listeners are interested in doing some research and getting up to speed on banks that look interesting in the wake of the sell off, any in particular that would come to mind?

John: Yeah. I'll just kind of go through my favorite banks. It's important to appreciate that. I've done an enormous amount of research. All of my research is focused on reducing and I've gone through different subject matters in this way. It's reducing that subject matter, it's a simple thing that you can then pack away and then just many years ahead you can unpack that. That's really what it's been about with banking. It has taken me a while a lot longer to get to that point than I expected. But where I came to is that the best way to think about banking is that banking is a business of abundance. It's about managing abundance. Most other businesses are about managing scarcity. When it's about managing abundance, as opposed to scarcity, that requires a different skill set, right? What is the underlying variable that allows somebody to succeed in an environment where managing abundance is the primary constraint? Where I have come to settle is that it is the innate or acquired immunity to avarice and envy, greed and envy. That's because when you're in a situation where managing abundance is the primary constraint, you can just go grab it all right now. Just go get all that. It's sitting there waiting for you to get all that.

Andrew: The thing every investor knows is the scariest thing in the world is a fast-growing financial institution. Because it looks great on the way up and there's, as you're saying, you can get as much of it as you want. Then two years later, the chickens come home to roost when all those loans that you wrote, are zeros.

John: Right. Darlings become pariahs. That is just every time. It's just the story of banking, the story of finance, right? You say, well, who can operate in those environments with people with these immunities? Then what you realize is that where can you ascertain whether or not people have these immunities. That's all in the personal, who these people are. You have to assess who these individuals are. I spent a lot of time getting to know these people on a very personal level. Then you step back and you think about them all in your head, you think you have all these people and all these vague intangible things that seem to tie them together like what are those things? That's my assessment of this. It's your point about the mark the market, the numbers don't really mean anything, right? They don't really mean anything. They do what they don't. You certainly shouldn't think that they do but certainly, they stand for something.

Andrew: As you said, look, you could have the best loan in the world, market at par, it sounds great. But if all your deposits pull and you have to sell it in 20 minutes, you're probably not going to get par for probably not even going to get 90% for it.

John: Or maybe like dinosaurs come back and they eat up the guy who [inaudible]

Andrew: The heat death of the universe is approaching at some point on an infinite scale. Everything's a zero.

John: Yeah, exactly. The banks that I liked the most are the banks with the best people that run them. There is a correlation between performance and these individuals. These are the best people that I believe in banking. Patrick Gaughen and his dad, Bob Gaughen, at Hingham Institution for Savings, HIFS. Now, they've been caught in a spot because of their funding structure. But they're through that. The thing that when you talk to Patrick about this, he knows history so well and he's learned all these different schemas through time and whatnot to do and what to do. The thing that Patrick Gaughen knows is that, when you go through a period like this, where things get scary, the temptation is to do too much, is to change your business model, to do this, to do that. When reality, you just need to sit back, chill out, and just let it go by. It's like when you're trying to get out into the ocean, you're swimming onto the ocean. You don't struggle with the wave, you go under the wave. You just chill and go under the wave. That's what Patrick and his dad know. HIFS, that's a terrific bank, terrific long term returns on that bank. Aaron Graft at Triumph Financial down in Dallas, Texas. I've met most of the top folks and spent considerable time with them. Aaron Graft is unique even amongst them. Just the way that he thinks, though, in the things that he does, it's very reminiscent of a guy by name of Andy Beal. Have you ever studied Beal?

Andrew: Yeah. Value investing circles, he is probably the most popular person. Right now, I bet Beal, he hasn't done anything so far in the past few weeks. But it is banks, it's on a lot of the things. There's a great article, this is what probably made it really famous, on him. Have you read his story about poker? I think it was in Vanity Fair or something. I mean, just absolutely excellent. But anyway, Triumph back.

John: What Andy Beal does, what's so brilliant about Andy Beal is that he expands and contracts the balance sheet like an accordion. That is ludicrous. It's so dangerous. But man, if you know how to do it, whoa, these things can fly. Because you have unlimited source of funding, basically. [crosstalk]

Andrew: As you said, managing abundance, right? It's managing abundance, you can get as much funding as you want, as quickly as you want by go out and take CD rates. Everyone else offering 3, offer 3.25. You can get as much as you want.

John: Aaron Graft is the closest to Andy Beal that I've ever seen in the banking industry. Aaron's funny because when Aaron, he was 30 when he bought Triumph, it was back in the day is called Equity Bank. When he bought it, he was going to run it like the Beal model. It's funny because the predecessor, the guy he bought it from and ran into trouble, was a Beal protege. I think he fancied himself a protege more than he actually was a protege. He ran it to the ground trying that model. But then when Aaron got the bank, it was too late. They missed the opportunity, took too long to convince regulators that a 30-year-old would be able to raise $45 million and buy this bank and get the thing up and off the ground, that they missed the opportunity to buy when they needed to buy. He's the guy, Triumph Financial, it's fascinating what they're doing. I think it's my opinion that that it's going to work. What they're doing is they're basically rewiring the payment system in the trucking industry, which equates to something like 8% percent of US GDP. It's a huge opportunity, enormous amount of success. They're beyond the point where they need to prove that it's working. It is working.

Now the question is exactly what the economics will look like. He's one. A buddy mine, his name's Brent Beardall. He runs a bank up in Washington called Washington Federal. Washington Federal, again, this is one of those banks that has not a lot of CEOs. One of the things you want to look for at these institutions is, are the CEOs coming in and out all the time? If there are, what happens when you're switching between these tenures or these regimes is that you'll have this institutional knowledge will leak out. Institutional knowledge in banking is really important. You want to retain that as much as possible. I think they've had seven CEOs since it was founded over 120 years ago or in around 120. I think it was founded in 1907. Now I think about it. But this is another bank that gets how this all works. That you just got to chill out when all these things are going on. They've had exceptional returns. That's one. Another one that I really like is First Financial Bank Shares. Have you heard of FFIN?

Andrew: No.

John: FFIN is run by a guy named Scotty Dueser. I love Scott and it's in Abilene, Texas, of all places. Have you been to Abilene?

Andrew: I have not. I've been to Texas a lot, but never to Abilene.

John: You've never driven west of Dallas?

Andrew: I have. I'm from New Orleans and we've done some road trips. You know what? Maybe west of Dallas. I'm going to say no, now that I think about it.

John: The west Texas man is like, whoo, like rascal.

Andrew: I mean, you start driving out there, you drive what? 50 miles and there won't even be a stop.

John: You're right. That is right on top of the Permian Basin. Really, Abilene is a little bit off the Permian Basin but it's right in that region. Boy, when that oil crisis hit in the 80s, I mean, all those banks failed. But for First Financial, not only did First Financial not fail, it actually earned money through the whole damn thing, which is crazy. Scott, and I were, he's been telling me all this stuff for all these years. He's told me that, "We've earned money every year since we were founded in 1890." He's probably told me that dozen times through the years. Finally, last year, I said, "Scott, it's time to put your money where your mouth is. We need to get that data." He went to get the data. He put two of his people on it. They spent a couple months digging it out through old board books and stuff like that. He comes to me and says, "Well, John, we got pretty much wrapped up. We're just missing one period of 15 years." I said, "Whoa."

Andrew: It's a pretty long period.

John: "What years are those?" He said, "Well, it begins in 1929." I said, "Well, I'm probably going to need to get those years." It's the Great Depression. They go to the OCC and the OCC is able to firm up that yes, indeed, they have earned money every single year since 1890, which as far as I'm aware, is the only bank United States I can say that. It trades for a huge valuation because it's so consistent in terms of its performance. By that, I mean that the standard deviations, the volatility of its performance in any given year is smaller than any other major bank.

Andrew: Let me ask about this one. This is a super small one, right? It's super small. Listeners should just keep in mind, not only is this bank and everything, but this is wildly small. They should keep that in mind. But I'm just looking at this. The stock trades for 30 to 31. The tangible book value there is six or seven and book value is eight or nine. That's a massive valuation. Silvergate and Silicon Valley traded for three or four or 10 times book for a while. Obviously, this is different but you look at that valuation and, hey, how are you going to make money as a bank investor buying a bank for four times book value?

John: It's actually not that small. I think it's something like 14 billion in assets.

Andrew: They've got 140 million shares outstanding, $30 per share. That would be what? Call it $5 billion market cap?

John: Yeah. I mean, insofar as banks go, it's not like a billion dollar.

Andrew: I think I was looking at the six number next to 140. But even that wouldn't be that small.

John: It's a decent size. Scott and I were talking about this just the other day. When you think about the value, it's created a ton of value over the years. It's been trading at these valuations, these three to four times book for 15, 16 years consistently. How do you catalyze value in that situation? Well, you catalyze value by using your stock to buy other banks. Your stock for three to four times book for buying a bank that's trading for one book or two times book. You can really catalyze value when you do that. We're talking about this, I said, "Scott, how much of the value you've created?" He's been the president of that bank since '91 or something like that. It's a long time. "How much of the value you've created is a consequence of all the mergers or the acquisitions you've done?" He said, "I don't know, but it's the lion's share." You are buying at high valuation, but that high valuation is a currency that Scott and his team uses to go out and buy these other banks to catalyze the value.

Andrew: I do hear that this probably gets into a more overarching conversation. It was like, hey, if you've got a company that's great at acquisitions, how do you start valuing them? It's really tough, because if the way they're creating value is issuing stock at four to go buy stock at one, it is a weird cycle. But let me switch from there. You've been very generous with your time. I do want to ask two last questions before we wrap up. The first one is, look, generalist interest in banking has probably never been higher since 2008, right? I got four text messages from people last week who said, "Hey, I'm going to open up the Credit Suisse 10k and really dive into if there's an issue here or not." I was like, "Look, if the governments didn't know a week ago that there was an issue, I'm sure you spending 20 minutes on the 10k is not going to reveal an issue." But just in general, a lot of interest in banks, right? People are going to start digging through and they're going to say, "Hey, I want to buy some banks, as you said, blood in the street, I want to start buying banks below tangible book. Or I just want to get a feel for how banks are doing because I'm worried we're going into another 2008 period, right?" What do you think when generalists are looking at banks? I'm an expert of reasonable knowledge. We're not talking somebody who doesn't know how to read balance sheet stuff. But when generalists are looking into banks, what is the one or two things that you think they don't put enough weight on that you think they should be thinking about going forward?

John: The first thing that I look at when I'm looking at a bank every single time is how they perform in the financial crisis. It does not matter how they perform in the good years, it doesn't matter. That tells you virtually nothing. In fact, it can actually be a red herring. What matters is how they perform in the crisis.

Andrew: WaMu was 20% ROE every year until they went to zero, right?

John: That's exactly right. I just go back and look at the financial crisis. Look at how US Bank did. Look at how PNC did. Look at how BB and T did. That's what you're looking for. Then in those cases, you say, well, if I want to buy bank stock and I wanted to use that as my litmus test, then you say, well, US Bank did really well. They emerged with the highest credit rating in the entire industry. even higher than JPMorgan. Then what you have to ask yourself is, is the culture and is the philosophy at the top still the same philosophy that got them through that thing? US Bank, I would argue that it is because the CEO, Andy Siri, was a right hand man with Richard Davis for many years. They both grew up under Grunt Hoppers. Grunt Hoppers grew up under this guy named Harry Volk at this bank, the Union Bank. My son just stole my hat. Union Bank in California. It's the same philosophy. In a case like that, you'd look at that and say that seems probably a pretty safe one.

Andrew: Just investors who are thinking about looking at individual banks now, as you said, go look at the financial crisis. If they were taking markdowns left and right, there's probably some, even if their balance sheet looks good. Because as you said, it's just numbers, they mean something until they don't. They might look good until next week, they're saying, "Hey, we're writing everything down." That's really the thing. Anything else investors, just in general, should be thinking about when they're looking at these stocks?

John: I mean, you have to approach investing in banks with a healthy dose of humility. That's what I would say. Because you get out there, what's that curve? It's the knowledge confidence or whatever.

Andrew: It's the one where you learn a little bit and you feel like you're the most confident. Then you learn a little more and you feel like absolutely nothing, even though you probably know five times as much. Yeah, I know exactly the one you're talking about.

John: It's like that. I mean, you obviously see people talking about valuations and numbers, this numbers that and blah, blah, blah. As soon as people start throwing that stuff out to me, it's like my brain just shuts down taking any information from them. Because you realize that they probably don't know as much as they think that they do. But what I would say is that that makes it really more complicated, right? That the numbers aren't as clean as easy to understand. But it also makes it a lot easier, right? Because what you need to do in this situation, when you're investing in banks, you just assess the individual that is running the bank. Just assess them. Does he or she gives you a good feel? Do they seem like an honest person? I mean, does their past lead you to believe that they will have success in the future? Make human decisions, make human observations. That's going to put you in a better position than trying to discern some sort of pattern out of some numbers that could be entirely made up. That's what I would say.

Andrew: I was going to ask you. I guess we'll wrap with this. But when you were talking about banks, you were saying, "Look, I like to invest in the banks, where I know that people I've got a lot of trust for them and everything." I think everyone would prefer to know everyone they invest in get a lot of trust in them, right? But the simple fact is, especially for generalists, but for most investors, they're not going to be able to get Jamie Dimon on the phone and learn Jamie Dimon. Now, you could probably learn a lot about him through the press. But if I'm looking at cable company and unfortunately can't get the CEO on the phone with me. But in banks specifically, do you think generalists who can't develop relationships with these bank CEOs, do you think they just need to throw banks on their do not invest list because they're not getting that human contact with them? Or do you think they maybe can just get a feel from as you said, going and seeing how the bank performed in the financial crisis, reading their earnings calls, getting to know them, just do that? Or do you think you really need that human sector specific focus hearing all the scuttlebutt throughout the industry?

John: If I were to show you when I go in and talk to these folks, my outline that I'll go on with an outline that's 50 pages long or 40 pages long. 30 pages of that will be genealogical research on the CEO. Who's his dad? Who's his mom? One of the first questions I asked is tell me what your parents did. Then you go off on that for an hour. We'll talk about the parents for an hour. I can't tell you how much time I spent doing genealogical research. Now it's almost crazy. You can find out so much from somebody from ancestry.com and just Google searches and newspapers.com. You can really start to draw a picture, not only who this person is, but who this person's family is, what the experiences, the things that they have seen. Those are the things that will lead you because what you need is somebody who's going to make the right decision at the right time. Typically, it's when everybody else is trying to force you or pressure you to make the wrong decision. You have to say, is this person going to be able to identify the right thing to do and then stand up the pressure that to not do the wrong thing? That's where this comes from. This history, the nurture element, and no, it's not what investors want because it's not some easy thing that you can put in an Excel spreadsheet. But the because it's not easy, that's where the opportunity is.

Andrew: Yep. I completely hear that. Cool. Well, John, you've been super generous with your time. I think we've covered just about everything I had. I mean, we could have gone off on tangents for hours and hours on this. Your genealogical standards, but anything you want to leave listeners with before we wrap this up?

John: Well, I mean, just self-servingly, you'd mentioned that I just started the Substack.

Andrew: There's going to be a link in the show notes. Anybody can go check that out. Absolutely.

John: Amazing. Check me out, Maxfield on Banks, on Twitter. I'm going to be rolling out a lot of research that I have done over the last 15 months. It's really fresh research. I talk about banking in a way that is different than I think most people talk about banking because of the geological stuff. But I think that if you're interested in this space, I think you will really enjoy the mental exercise of going through and looking at these things in that way. I would just say, come and check this stuff out. If you don't like it, if you disagree with anything, let me know. I have pretty thick skin.

Andrew: Great. Well, I am looking forward to the posts going forward. Again, there'll be a link to it in the show notes for anybody. It is maybe the best Substack launch of all time. The only thing I think could have been hotter was maybe if you were a biologist launching in February 2020 or something, it might have been a better timing. But aside from that, I can't think of a better time to launch a Substack. But, John, appreciate you coming on and maybe looking forward to having you on to talk banks again in the near future.

John: Yeah, you're awesome, Andrew, appreciate it, man.

[END]