Net Interest's Marc Rubinstein on $COF and if Silicon Valley Bank has fundamentally changed banking (Podcast #171)

Marc Rubinstein, Founder and Editor of the Net Interest Newsletter, is back on the Yet Another Value Podcast to have a wide-ranging discussion digging into Marc's thoughts on the current state of banks, financial sector, as well as dissecting his article on what makes Capital One $COF interesting.

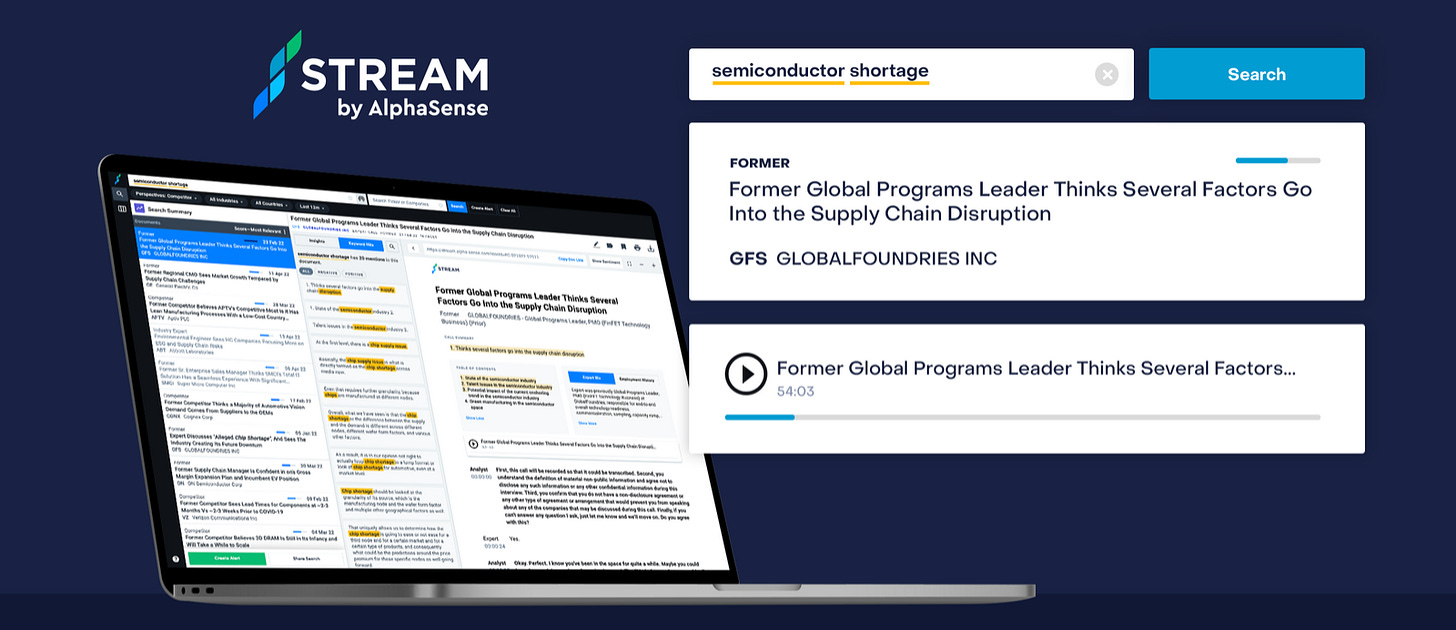

***This podcast is brought to you by Stream by AlphaSense.***

Expert calls just got easier.

Say goodbye to traditional expert networks with Stream by AlphaSense. Stream enables you to access high-quality expert insights, in less time and at lower cost. With proprietary search technology and a library of more than 30,000 expert call transcripts, Stream provides the tools to help you make smarter decisions faster. Sign up today.

Please follow the podcast on Spotify, iTunes, or most other podcast players, as well as on YouTube if you prefer video! And please be sure to rate / review the podcast if you enjoy it, or share it with someone else who would enjoy it (more listeners is a critical part of the flywheel that keeps this Substack and podcast going!).

Disclaimer: Nothing on this podcast or on this blog is investing or financial advice; please see our full disclaimer here. The transcript below is from a third party transcription service; it’s entirely possible there are some errors in the transcript

Transcript begins below

Andrew: Hello and welcome to yet another Value podcast. I'm your host, Andrew Walker, and if you like this podcast, it would mean a lot. If you could rate subscribe, follow, and review, wherever you're watching or listening to it. With me today, I'm happy to have you on for the second time because Marc, I think you are one of the first 8 guests on the podcast. I didn't look at the exact number but way back when we were getting started. But for the second time, Marc Rubinstein. Marc is the founder and writer of net interests .co, which is very much in the mindset right now. Marc, how's it going?

Marc: Hey, Andrew, a pleasure to be back.

Andrew: Well, really happy to have you back. Let me start this podcast the way I do every podcast. Just a quick disclaimer to remind everyone, nothing on this podcast is investing advice. That's always true, but I think our goal today was to talk about a lot of companies in the financial space. So people should remember if we're talking about a lot of companies even risk here, Lots of companies. Please do your own work. Things are going really quickly in the financial sector right now, so sort a financial advisor, this isn't financial advice. Mark, the kind of the reason I reached out have you had this incredible piece, which I'll link in the show notes, covering Capital One about 2 weeks ago, which I think is a really interesting company, but then you've also written about Charles Schwab as another really interesting company, and you've just been at the center of the hurricane that's sitting in the financial landscape right now. So I'll pause there. We can talk Capital One. I want to talk to Schwab a little bit but just overall. We're talking here on June 6th. What are your thoughts overall? What's going on in the financial landscape?

Marc: It's interesting. People are going back to trying to understand what, there are various points in the cycle where people have to relearn what a bank actually is. A bank is a shape-shifting entity. There are times when it projects growth. There are times when it projects value. There are times when it projects a bond-like instrument [inaudible] that. And I wrote a piece a few weeks ago, which makes the point that a bank is less a business and more a balance sheet. That the best mental model for thinking about a bank in good times and in bad, especially in good times, is that it's a balance sheet. It's a collection, it's a portfolio of assets, fund willed by some mix of funding instruments, which may be deposited.

The trick of deposits is that they look like they're long-term and the bank is structured to exploit that long-term nature of deposits. But we've known throughout history, and we were reminded again in March that that's not always the case. The Silicon Valley case is really interesting because more than most banks, Silicon Valley was seen as a business. Actually more than Silicon Valley, First Republic was embraced by investors. I would have discussions with investors historically who would look at First Republic with a very different lens from the kind of balance sheet mental model that I would employ.

This is the best business, with phenomenal customer service, and a whole narrative around that. And the stock was trading at a big premium to tangible build value to reflect that and how quickly that can change. And I suppose just to answer the question, that's just by way of background, we're now 3 months on but we never actually got over the financial crisis 15 years on. Banks never globally got back to the kind of valuation multiples that they were trading at prior to that, muscle memory is very long, and here we are again. So fortunately for investors who have the ability to be opportunistic, unfortunately for executives within the industry, the market has a very long memory and it can take a long time for these things to recover.

Andrew: Look, you hit so many things that I want to talk about because we're here to talk about Capital One, and I'm just typing notes on the screen, and I've got 7 follow-up questions to everything you just said. So let me start with a few. So you and I were talking before, I think anybody who's been reading what I've been putting out on the value blog, or I'm working on a letter from my investors like I'm really interested in banks right now, and I more look at banks, as you said, the quote ahead was, you said banks are balance sheets. And I look at banks as banks are balance sheets. You can pay more than tangible book value and if you think it's going to earn good, you can pay 1.2 or 1.5.

But one of the things I was surprised by is, you look at some of these banks that exploded and a month before they explode, silicon Valley Banks valued at like 3.7 times their unadjusted book before incorporating the Health and Maturity securities that actually took them to Infinity Times book, first Republics at 3 times Silver Gate if I remember correctly. Is that like 10 times book value because they're a growing crypto bank, and I don't think anybody wants to pay 10 times a week? But my question to you is, can you pay real franchise value for any bank? Or is the right answer always to be looking at banks as banks are balance sheets? I Can pay a little more than the tangible book. I can pay a little bit less, but I can never pay more than 2 x because they are balance sheets. There's not really a franchise there.

Marc: Yeah, I guess you can pay. you can plug that gap by thinking about sustainable return on equity, the extent to which a bank is able to generate a sustainable return on equity in excess of its cost of equity that will justify a premium to book value. Jamie Diamond, always a go-to analyst in the banking industry every year, writes a very lucid shareholder letter, and he talks about valuation. It's the best lesson in how to value a bank, is his shareholder letter. He talks about valuation being anchored to tangible book value and that his goal is for growth and tangible book value. But nevertheless, it is in his view, the anchor. Every time I've seen a bank, there's a great example here in the UK where I'm based, I'm going back 20 years.

It was the biggest bank in the world at one stage in terms of market capitalization. It was Lloyd's, Lloyd's bank traded at a big premium to tangible book value. And it suffered in the financial crisis whenever City Groups, another example, didn't trade at such a premium to book value, but it was one of the biggest banks in the world at one stage. And there's just a cyclical component to it driven by a number of factors, kind of mean reversion in terms of asset prices, but also kind of complacency sets in. And I've studied banks in the past frequently. I've got a whole series of mental models when trying to understand them. We've spoken about one. Another one is that the same crisis, banks are prone to crises for various reasons, but it's never the same consecutive crisis.

Often, it's diametrically opposite. So, the one we've been experiencing recently was interest rate driven rather than credit driven. It was driven by retail deposits rather than wholesale funding. Diametrically opposite to the playbook from 2008. Often the bank that has had the most successful crisis will then be prone to a slip-up in the next crisis. Maybe it's management complacency, or maybe it's simply that the regulators aren't focused on its business mix but that tends to be the case and no bank is immune.

Andrew: For both the First Republic and Silicon Valley Bank, I haven't looked recently, but I would bet good money that their loan losses were better than 90% of their competitors. Part of that is because First Republic was funding super-prime creditors with under-market interest rates. Especially in March, a lot of the investors I would talk to would say banks are black boxes. I can't look at their balance sheet, how do you mark these? And I'd say, I hear you we can't go in and know the details of every loan, but I think you're applying a 2008 mindset where you would see these banks that had AAA securities on their balance sheet that turned out to be worth zero. And that's why they blew up.

And that is not what happened here. The marks were accurate. I remember January, you could look at Silicon Valley's bank, and I've got a tweet from February. I can timestamp [inaudible], you can see, hey, held some maturity securities, they're worth less than the entire shareholder equity of this bank. And it was just a trust game. That deposit was never pulled. They'd never had to sell them. They could realize those and that trust game ran out. So, yeah, I'm with you. It's so diametric close. Let me ask one more. You said a lot of the banks never got over the financial crisis, which is certainly true. This is going in a completely different direction, but one thing a lot of investors have asked me about the banks is, a lot of banks are trading at or below tangible book value right adjusted unadjusted, however, you want to do it.

Historically, that's been attractive in the US but if I go over to Europe, there is a bunch of banks that have traded for half of book value for years. In Japan, there are a bunch of banks that have traded for under-book value for 30 years. And a lot of people have asked me why we know, the zombie bank issue, it’s kind of a zombie bank that they just stumble along for years, never create shareholder value, but they never go bankrupt. We are about to have a lot of banks that kind of just become zombie banks. Why is a tangible book good? Why can't we go to half a tangible book for a long time?

Marc: I'm based in Europe, I'm with the European banks extensively over the years. Right now, about two-thirds of European banks trade in a discount to tangible books. And even prior to March, the majority traded under the discounted tangible book value. There are a number of reasons for that, principally profitability but there are a number of underlying reasons for that. One is large, it's a kind of corporate finance theory that if any asset trades at a discount to its liquidation value, then it should be liquidated. Then private equity would come in and liquidate your assets. And I guess the friction arises because private equity is in many cases excluded from participating in this sector because certainly in the US and in Europe, bank holding company legislation and restrictions over who can own a bank.

But also, the costs and we're seeing this to a degree with credit swiss. Some distinguishing here between the large banks and the smaller kind of regional community banks, but the large banks, I think of it like it's kind of the Hotel California effect. It's very easy to get into some of these businesses that add to the complexity that fuels the overall balance sheet size. But it's very difficult to get out. I look at say Deutsche Banks’ balance sheet, and it's the same frankly for JP Morgan and Citigroup. Citigroup is a great example. The new CEO Jane Fraser has been in her position for 2 years now. She's been articulating a simplification agenda. And again, we're 15 years after the financial crisis and she's still trying to simplify the business. Takes a long time to sell off those assets, and spin-off businesses, and they've just been stymied from a sale of the business in Mexico takes a long time. So it traded at a discount a book fine, but capturing that discount, even the bank itself, and certainly this sector is a graveyard for activists, very difficult for an activist to go in and try and close that discount because of the complexity involved in some of the businesses.

Andrew: I 100% agree with you, but I do think there is one thing where something like Citigroup or UBS. These are a hundred billion dollar plus companies. Very difficult as an activist to get a site where you can even kind of shake the company up there. I think the second thing I'd say is in the US a lot of the companies I'm looking at are, or the banks, they're regionals, the community banks. And there is the question is the book value, if it trades at 5 and the book values at 10 and it turns out they've got $8 per share of losses on the books or something, that's a different story.

But I do think there is something like, and you can tell me if I'm wrong, I don't think they, Europe or Japan have these small community banks that are kind of publicly traded. And I don't think they're as open to, you mentioned activism, I think activism at small banks actually can be quite successful because you go in, you've got a little small bank with the community deposits, it's got some loans, very easy to diligence, especially for a buyer. And if you're the buyer, if it's a little town, all the buyers in all the towns next to you are really, that's a very inquisitive deal. So it's very easy to go in with activism. It's a simple sale playbook. I think people think of Europe and UBS, Credit Swiss, as you mentioned, those are very difficult to do this because there's one buyer, if any, it takes the government’s blessing, It's crazy complex but if it's Community Bank of New Canaan, pretty easy to go in and sell that to Community Bank of Old Canaan down the street.

Marc: That's a good point. You're right. The US is unique here. It's a happy hunting ground for bank investors. 4,000 banks in the us It's a capable, intensive industry and so therefore they tend to be public rather than privately owned. Although there are credit unions, there are another 5,000 credit unions as well and we don't have that. There are many more banks in the US absolutely per pop, per GDP than in any other country in the world. So that's absolutely clear. And that can be an opportunity for investors and for activists. You're absolutely right.

Andrew: Do you think we see a wave kind of bank consolidation not in the JP Morgan and city groups region, but probably the regionals and the smaller players? Do you think we see a wave of consolidation on the heels of this? Because we were already seeing a little bit of it earlier. A few banks that follow there, their emergent stuff. But I do wonder just you probably get regulatory burden going up re burdens already very high in the US it probably goes up on the heels of this, the tech spending. One of the things that were killing community banks is they're at versus we're in an online world, it's the thing that killed Silicon Valley Bank, you could do 40 billion deposit polls in two hours if you needed to. But the tech spends everything that's going up and that does favor the larger players. I just wonder if this is the last straw, we'd really see a wave of consolidation on the heels of this.

Marc: Yeah, look, we're seeing it anyway. We're seeing focus consistently since the mid 19 consistency since 1985. We've seen a steady decline in the number of banks in the US we've seen consolidation. And whenever there's a crisis, it's an opportunity for a large bank, JP Morgan, whether it was Washington Mutual in 2008, First Republic, now to just push the envelope a little bit and get just that little bit bigger. I think it's inevitable. Broader reasons you say. However, our mutual friend Bernard Hobart did some analysis actually where he looked at donors to Congress people and the community banking lobby is a very successful, very relatively aggressive lobby. And we saw this actually when Janet Yellen was grilled on the hill. The extent to which the preservation of community banks, and smaller banks is so important culturally to much of America. So that may not change, but in the middle piece, we've seen it. We've seen SunTrust, BBT’s really bad timing in that the First Horizon deal was called off as this crisis was playing out. Really bad timing.

Andrew: First Horizon is having an investor day right now. I was listening to it up until we started recording the podcast. You mentioned Bernard writing about the strength of lobbying for small banks. Small banks have a lot of disadvantages. JP Morgan has national marketing, they can probably hire the best bankers, and they can really leverage the tech spending over a much bigger asset base, which is massive for tech spending. But the small banks have one huge advantage, and that's regulatory where their regulatory burden for making loans compliant believe is much lower. But even ignoring all that, just the capital costs. The crazy thing about JP Morgan is they run about a 20% return on equity with capital, and they hold common equity as a percent of assets. That's probably a quarter or 10% of their size So, if I'm a $200 million bank, I probably can get a 15 to 16% return on equity if I'm pretty good. I think that's what the good ones do. JP Morgan gets a 20% return on equity and they hold double the amount of capital. So their return on assets is probably three times as high as the community bank. It's just crazy how good they are.

Marc: They're targeted at 17. This is a point, [ Inaudible] had their own investor three weeks ago and this point was made. They're targeting a 17% return on tangible. Their capital ratios are materially higher because they have to hold 4 and a half percent against risk-weight assets just for being big and complex. And they subsidize the system ultimately because, in addition, the big banks are taking on more of the FDIC deposit insurance assessments relative to the regard just on an ongoing basis. In addition, they're taking on more of a special assessment linked to the recent losses. FDIC has suffered. Clearly the FDIC, there's this notion of bailouts and the FDIC theory is an industry, the FDIC is backstopped by the federal government, but on a day-to-day basis, it's an industry cooperative unit that is funded by the industry. And therefore, deposit insurance, which benefits smaller banks more than the bigger banks because they're not too big to fail is heavily subsidized by the bigger banks. It comes back to the point about the degree to which this structure is embedded within American culture. Jamie Darwin can't complain about it.

Andrew: It makes complete logical sense. I never really thought of that. I just always thought about it benefits everyone. But you saw in March if you were desperate and you were going crazy, where were the 2 places, the 3 places you could park money at JP Morgan? It was Wells Fargo and it was City because they're huge and they're safe. But you also knew they had the implicit back of the government. The government's not going to let those guys fail. If City goes under an unsecured, depositors take 97% of the dollar, which destroys the economy. So you're fine. But because of that, FDIC insurance, it's probably whatever for them.

Whereas a community bank, if you didn't have FDIC insurance there, no one would keep money there, there they'd all be at JP Morgan. So JP Morgan pays in the system and it benefits someone else. Let me turn to Capital One real quick. So again, the reason I reached out [ inaudible] Capital One, which I think is just an absolutely fascinating company, is you did a great write-up on their history there. At this point, they're the third largest card issuer. They get started in the eighties and nineties. They kind of figured out a loophole for getting better returns on credit cards. Now they're the third largest card issuer. They've started going into banks. There's a lot of stuff I want to talk about them because I find them a fascinating company. But I'll turn it over to you. Do you want to quickly go through the history of Capital One and what makes them so interesting?

Marc: Well, interesting, you're right. I look at a lot of FinTech companies, and financial technology, and there's nothing new under the Sun. Capital One was arguable, but I guess technology is as old as time. So, which was the first financial technology company, I don't know.

Andrew: It was Bank of America introducing the credit card in the fifties or maybe people were doing stuff before then. I don't know.

Marc: Probably. Visas are good. Visa could be one. Capital One changed. Capital One changed the way the credit card business was run. And it was so successful that it has many copycats all around the world in various emerging markets in India, Brazil, in Russia. So, they launched a credit card in a slightly differentiated way, used direct mail in order to market it, and differentiated on price, which was the innovation but then ran into problems 20 years ago. Random problems in the early 2000s came back a little bit to what we were saying earlier, that no 2 crises repeat consecutively.

And actually, if you go back through the modern era, you can almost alternate between wholesale funding and retail funding crisis.

20 years ago, you had a wholesale funding crisis that caused many subprime lenders actually to fail but caused Capital One, which at the time didn't have a deposit franchise. It was funding its credit card receivables, either via securitizations, all via warehouse lines wholesale. Actually, like a lot of fintech, today grew too quickly grew its balance sheet and grew its business more quickly than its compliance function. Arguably, like many fintech, many high-growth financials are in the market today and that caused a market scare wholesale funding costs.

Actually, they ultimately ramped up, but before that, wholesale funding just disappeared completely. They were able to navigate that but the CEO who's the longest-serving financial company, CEO globally, probably with the exception of Warren Buffet if you regard Berkshire as a financial company. But globally, Richard Fairbank is longer serving as CEO of any financial company globally. He founded that company and he came back. He came out of that with the idea that actually they need to turn into a bank in order to raise deposit funding, all of the benefits of deposit funding we've just spoken about. That's something he wanted. And so, in 2005, 2006, he brought a pair of banks and just changed the whole business mix.

Andrew: One of the banks he bought was Hibernia, which I'm from New Orleans, and my dad worked for Hibernia, and when they bought out that's how he retired. I've been familiar with Capital One for a long time. And actually Capital One I remember specifically, they were set to close on a Monday and the Thursday before Hurricane Katrina hits New Orleans. And Hibernia might have been bankrupt, I don't know. I was in high school, and I wasn't analyzing bank balance sheets, but Hibernia struck the deal but they did close it. And I think that was probably good for all of the New Orleans economy. And it's crazy how one little deal if Capital One decides to claim MAE, maybe I would've done the merger back then, but it's just crazy how things switch.

There's one thing I did want to say before we go back to Capital One. You mentioned back in the 2000s, they learned they grew too fast for our systems. And I just want to go back to the crisis we're having right now. It is funny, the old adage is there's nothing worse than a fast-growing financial. And everyone's heard it. I always equated it to when you're a fast-growing financial, you make a loan today and it doesn't come back to haunt you for normally 3 or 5 years, So you're a fast-growing financial. Maybe you're making all these loans in the problems in your book. You won’t discover them for 3 years. And actually, if you grow fast enough, it might not be 5 or 7 years because you grow so fast that, in year one's problem loans, you don't even notice them in the context of your balance sheet by year four because you've made many more. That's always been the adage, but it just struck me, Silicon Valley Bank, and the First Republic, were fast-growing banks, but the risk was on, they grew too fast on the deposit side. And especially Silicon Valley banks appear to have grown too fast for their internal tech systems, risk management functions, and everything. So just another thing on the fast-growing bank adage.

Marc: That's right. And it's fascinating. You talked over about a black box, about a bank being a black box. What's useful for the outside analyst of the sector when a bank runs into difficulties is the material that is then published after the fact. The bank doesn't have to go bust that to happen. We got a great insight into JP Morgan's treasury operation in the aftermath of the London whale grading loss in 2012, the bank commissioned an inquiry, which is publicly available on its website and gives you a real insight into what goes on inside the bank's treasury business. The same credit Swiss, obviously the bank now is no more. But in 2021, when they suffered that loss on our [ Inaudible], they commissioned a law firm to make an investigation into what went wrong. That gave phenomenal insight into how a prime brokerage operation works or should work.

And to your point, right now, we've had FDIC and the Fed file reports on postmortem reports on Silicon Valley and Signature Bank, and they're just fascinating reading. Your point about tech is a really good one. Turns out we all thought Silicon Valley Bank, by definition, was probably likely to be good at Tech, turns out, according to supervisors, their tech actually wasn't that good. And they were reprimanded for it prior to their ultimate collapse. And another thing that came up again to your point about the kind of misjudging risk is the duration of deposits. They had an assumption they modeled an assumption duration of deposits which and ultimately their risk profile breached their limits. So they changed the model. They change the input rather than make a business decision.

Andrew: I have made this point before, maybe on this podcast. I cannot believe, when you look at Silicon Valley Bank, off the top of my head, $80 billion of deposits on December 31st of that 80 billion, we now know somewhere between 6 to 8 billion. So, 10% was a circle, if I'm remembering correctly. Circle had 8 billion in uninsured deposits at Silicon Valley Bank. And then on top of that, Roku, if I remember correctly, has somewhere between 500 million to 750 million in uninsured deposits just sitting at Silicon Valley Bank. And it just blows my mind that Silicon Valley Bank could look at this and say let's just round it up, 10% of our deposit base is an uninsured deposit from one customer who 3 years ago wasn't even here. We don't know, we're talking June 6th, and the feds just sued Coin base today, I believe Coin base gets tons of revenue from Circle, but we don't even know if this is a legal product security. We don't know how the future's going to evolve. And they just thought 10%. Like you would've thought, at least you matched that with extremely short-term absolute liquid. And no, they just parked it all in deposit absolutely crazy to me. You can comment on that or I can do a quick follow-up on that.

Marc: So, the only thing I would add to that is, it's almost like the kind of amnesia effect here, which is that Silicon Valley is [inaudible] to book value, everyone thought it was fine until it wasn't. And after the fact, we then learn a lot more, some of which were public, the uninsured deposit number was public. Their value of the how-to maturity securities was public. These were nuggets of information that were available to any analyst, any investor, any customer but then all of which is public. The idea that they weren't good attacked the idea that they were changing their risk models. The idea at Signature Bank was that management just kind of wasn't returning supervisors’ calls. And the way it works, this is probably true globally, but it's embedded within the law in the US they call it confidential supervisory information.

By law it's confidential. You would think this is superior to any kind of SEC requirement to disclose anything to investors that regulators know. Stuff that investors are not allowed to know. Once you see this, it comes back to why these things may be a discounter book. If that was the case in Silicon Valley Bank, if that's the case in Credit Swiss, what's going on? What's going on at JP Morgan? What's going on at Capital One? I don't know regulators.

Andrew: One of the best arguments, and I think anybody who's read my right names is I think banks are really attractive right now. But one of the best arguments is a year ago, if we had had this conversation, you and I, if we talked about the First Republic, if we talked about Silicon Valley, we might've debated valuation. We probably would've focused on valuation if we believe the depository was real. We would've never, I, I don't think in a million years we would've thought they would be at zeros. And we both would've been like, these are two of the best banks out there. these are two of the best banks out there. I don't think either of us would've been talking about their risk culture or internal issues with their technology. Like no, just wouldn't have come up. We would've been talking about the quality of their franchises.

And the argument is, Hey, yeah, you can go buy stuff for a tangible book right now. But if you had seen, as you said, if you had seen what the regulars were saying about Silicon Valley Bank, you would've paid tangible book. You would, you have paid a fraction maybe, but maybe not. , like yeah. let me, we were talking about the internal reports before. And you mentioned Silicon Valley Bank. I think we've done on them a lot. You read the report and I, I've kind of only glance answered, so I can't claim to be super driven too, but you read the report and you're like, oh my God, these guys were just way out over their skis on this. Is there anything else you kind of learned from reading this round of the bank failure reports?

Marc: Well, so the other point is, and it's not an original point particularly, is this notion. The question is, has something changed? Has something fundamentally changed in the way banking works? It's not an original observation. People have been making it since the 10th of March, but this was fast. And even when we look at concerns like Pac West the degree of attrition of deposits is like nothing that has happened before. I was short when I ran a financials fund many years ago. I was short Washington Mutual, kind of December 2006. It took a long time to play out. And actually, there were three rounds, `and this wasn't the reason why I was short, I was short on traditional kind of asset quality concerns. One thing we've discovered after the fact is there were three separate rounds of, there were three runs. There wasn't a single bank run. There were three discreet runs on the bank. One was when Indie Mac failed 1and then there were three discreet bank runs `which have been documented. And each of them, even in aggregate were smaller than obviously what we've seen recently. I would say it's not an original point, but the duration of deposits, we had to recast that.

Andrew: 2006, 2008. I think there was online banking, but people weren't really using it. It probably wasn't the speed, if you wanted to a bank run, it's the line of people outside the street, and yet the line of people outside the street can induce fear. But guess what, you can't pull a billion dollars with a line of people outside the street. Because human tellers have to like literally write every individual check and they have to go deposit them. And in this case, as you said basically every deposit left Silicon Valley Bank within 24 hours. Like nobody was prepared for that. If we're going forward, the bank CEOs are prepared to address this, every bank CEO now has, here's our liquidity, here’s how we're ready. We have a 100% of our deposit base in cash on the balance here, or whatever.

They put all those things. I do think it is an interesting question. Regulators are going to have to grapple with this. Every deposit in the bank can leave within 24 hours. How do you run a bank where a bank's business model is, if the simplest is borrow short, lend long? How do you borrow short when a bad headline? I think the short seller reports are crazy, but short sellers can gang up and say, this bank's terrible. And if you're a deposit, if the short sellers, if there's a 1% chance they're right, that's a disaster. If there's a 99%, they're wrong. You've got to worry about the 1% there. Pull now and come back later if you can. So, if you're a bank regulator or you're a bank, how do you think about that going forward?

Marc: A more optimistic spin is as follows, which is, I guess the bear case is why does anyone, [Inaudible] case is the new market funds are let's say 5%. Why is anyone bothering with a bank? And, the reason is not everyone bows down to rate. There's a convenience factor as well. A deposit, it's kind of a bundle of features rate is one of them. instant liquidity is another. Convenience is another, and a relationship with the bank manager, with the bank is another that was put in a bad light. Again, coming back to Silicon Valley, this idea, if you want a loan, you have to retain funds on deposit with us was kind of seen a bit badly. Various politicians asked questions of the bank, but it's acceptable.

Andrew: It’s funny that because every bank I would listen to, would say if you were one of the people who pulled, we remember that we look at a wholesome relationship when we make loans. So if you pulled all your deposits, we're probably not going to be there for your line of credit. We're probably not going to be there for your next loan because we need a wholesome relationship to do all of this type of stuff.

Marc: So that's exactly right. So that's fine. Lots of features. So deposits they're not going to get a zero. This idea is that deposits aren't going to get a zero, but we've got different types of deposits. And actually, there is a framework already, a liquidity coverage ratio, which looks at different types of, not just insured and uninsured, but different types of deposits, operational deposits, normal operational deposits, all deposits, household deposits, and then whether they're insured or uninsured, all different spectrum of deposits which have different risk factors and ultimately different durations. Actually, the evidence is that most of those buckets behaved, and most of the deposit contraction has come. If you look at Bank of America, and Wells Fargo as a segment, their deposit, it's coming out of wealth management. Charles Schwab.

Andrew: I've got some questions on Charles Schwab on here. Great article on that too.

Marc: It's coming out of Ralph Management, which makes sense, because if you think about the features that their customers rate.

Andrew: It's coming out of wealth management because a wealth management account is a brokerage account, You and I have a $100,000. We're saving that to grow. We're investing in the stock market. We want to grow it. If we have $5,000 of cash there, it's to buy stuff opportunistically in the future. It's not to write checks for our household expenses or for rent. We're really thinking of that as an investment. So, if things get hairy, we need that $5,000 can get out, and we're already thinking about growing that, so why not shift it from a cash that earns nothing to a money market fund or a short-term bond or something like that? Like it makes all the sense in the world. Whereas your checking account, which you're writing your rent, you're getting your deposits in, you're using to pay your utilities, you're not really thinking about, I need to maximize my interest rates on that. Maybe it's suboptimal, but all sorts of human behavior is suboptimal. So, it does make sense to me that the wealth management sweep is where most of it would be because that's where you're really looking to get your best return.

Marc: Exactly. And that is one side of that. Credit Swiss is a great example because Credit Swiss was a slow burn. Unlike Silicon Valley, Credit Swiss suffered its first maybe a bit more like Russian to Mutual. There was a series of runs. The first one was on October, 22, 6 months before it went bust.

Andrew: When the internet discovered CDS charts and said Credit Swiss CDS went from 20 to 100. And yeah, that's a big increase. But it's also, this is a thin market. A 100 isn't that big in the grand scheme of a CDS, but first run.

Marc: Exactly, but if you look at those classifications and deposit types where the risk was identified, the risk was in an uninsured wealth management type of deposits. So, the framework is there for an outsider to understand this risk and companies will be more transparent about it, but deposits aren't going to zero.

Andrew: The other thing I think people miss is deposits. People probably think about deposits like you and me themselves. They think about their deposits, what they're getting. A lot of these, as you said, are operational deposits, It's, GE has an account that they used to pay hundreds of thousands of people on their payroll that they used to pay hundreds of thousands of vendors. And you can correct me if I'm wrong, but I believe in operational deposit like it's definitely a 0% checking account and you can't just sweep money in and out to money market funds. Like you need to have that money in there to fund your daily operations. And those are kind of the golden ticket for banks. And that's what a bank franchise is really built on and the under 200,000. But that's really where the banks build their franchise and those just can't sweep over to a money market. Tell me if I'm wrong.

Marc: Yeah, that's right.

Andrew: Turning back to Capital One. So of course we talked about Capital One and we're talking about everything else, but I do want to start with Capital One. So, let's just fast-forward today. Capital One in the past, they are a credit card issuer. They figure out some tricks. They're very technology-driven, as you said. If we fast forward today, they bought some banks and their basic business model is we use the bank side to fund mainly the card issuer side.

They have other businesses, but now they're the third largest card issuer. Card issuance is over 50% of their business. And if you're doing credit cards at 18% interest rates and funding it with 0% deposits, it's actually a pretty nice business. I want to ask you a few questions about them. They were at a conference recently and someone asked them, you guys in the past have bought regional banks to fund your business? Regional banks have been smashed. Would you be interested in buying a regional bank now? And they said, no, we're out of the buying regional bank business. We see value elsewhere. And we could go a lot of places with that discussion. But I just want to ask, why aren't they interested in buying regional banks anymore?

Marc: If you look at the balance sheet now, they have 350 billion deposits. Their last banking acquisition was ING Direct, which wasn't a regional bank, but it brought in and gave them what they wanted. It was online deposits, brought them. So, the 300 billion deposits they got a bit less than 300 billion of loans. So, they're skewed appropriately in the current environment between deposits and loans. And the First Republic was the other way around. I think what they've realized through this, is cause their deposits were up in the first quarter. Actually, there was a Wall Street Journal article about this, this week we were talking on the 6th of June. It was Monday, the 5th of June, was a Wall Street Journal article making the point that two banks whose deposits were up in the first quarter through the turmoil in the middle up to the end of March. Were Ally and Capital One?

Andrew: Well, let me just jump in there because this is where I was trying to drive the conversation. Ally and Capital One have gone, not branchless, cause Capital One does have branches and they've experimented with the Capital One little Café and everything. They still have the legacy at the Bernie branches. But Allies Branchless, Capital One is largely online. And it does strike me that both these businesses that try to do largely online to attract their depositors. So that involves lots of marketing and very slick online technology. It does strike me that Berkshire owns a significant piece of Ally and they just bought a significant piece of Capital One in q1. And my question is, is Buffett seeing where the pucks going? Capital One and Ally online Focus Banks, that's where the puck is going.

Marc: Puck's been going now for 20 years, Interestingly, the antithesis of that argument was a bank called Commerce Bank Shares, which was built now TD. Vernon Hill I'm told he owns the biggest house in New Jersey was the founder and chairman of Commerce Bank Shares. CBH was its tacker. He sold it in 2008 to TD. He then came to the UK and set up Metro Bank in the UK. And his thesis was to do really nice branches and to compete with the internet banks by paying less, but if you include the OPEX of sustaining that branch network all in the cost would be similar. It's difficult now to actually disentangle within TD whether that strategy still persists. But I think he's lost. I think he's lost that argument.

Andrew: I probably would agree with you. We mentioned at the top, the First Horizons Investor Day, TD tried to buy them at the start of 2022 for what worked out to be about two and a half times tangible book value. So that deal fell through for reasons unrelated to First Horizon. They were very TD related. But I would look at that deal and say as recently as early 2022, TD looked at their bank branching model and said, yeah, we want to lean into having branch coverage. Because their argument was, you put First Horizons branches with our branches and it fits like a glove, it fills in all the little spots that we don't have. Let me ask a different question.

Marc: We've spoken about fast-growing finances being a red flag, another red flag that I often look at is who's at the top of those Best Buy tables? Who's offering the highest deposit rate? Because inevitably, or maybe it's like the wine list on the menu, you go for the second cheapest. If you're two on the Best Buy table, you are in need of deposit funding and that's a red flag. And actually, in a lot of the cases why the card was up there in Germany there was a company called Green Sill Private company owned a German bank that went bankrupt in the UK in 2020. They were up there. Often, a lot of these failures you will find have been desperate for deposit funding. And they've been up there. So you need loyalty. The hot money isn't the best money.

Andrew: And you can do hot money. Andy Beal made a fortune in the global financial crisis getting hot money on the deposit side because his advantage was he was buying assets for a song. But if you're a bank that's always trying to fund with hot money, you're the highest payer. You've got the highest cost. It is interesting. Ally in Capital One, I can't remember which, but I was reading their call yesterday and one of 'them said to go look up our CD prices. Are we higher than the branch down the street? Yeah, probably. Because the branch down the street has to fund all the overhead costs of having the branch down the street. So we're higher than them, but we're probably like the 80th percentile of height. We're not the absolute top tier.

Here's the hottest money and we still attract people because we've got a good brand. So we pay more than the lowest, but we pay less than the highest. And that's probably the right spot speed. Let me ask you a different question about Buffett's investment in Ally and Capital One. So one way to look at it is, hey, these guys are largely online and that's where the puck's going and that's probably right. But the other way to look at it is, Ally and Capital One, to my knowledge are the most consumer-focused banks. The vast majority of their loan book is for Capital One credit cards and for Ally and then secondarily Capital One is auto Loans. So it's this huge diversified pool of consumer books. You go into a consumer recession, maybe that's bad, maybe they're over reserved, who knows, whatever.

We can talk about that. But it does strike me, every person I talk to worries when they invest in a bank. It's all commercial real estate and it's all downtown skyscraper loans that are empty and going to zero. That's not the case. But if I looked at a First Horizon or one of these other regionals, a lot of the book is commercial real estate and they can be chunker loans, it's a little bit harder. Whereas if you look at a credit card book with 10 million loans in it, you actually can place statistics with that even from the outside. So, I want to ask you is Buffet attracted to the online side or is he actually attracted to the diversified, consumer-focused nature of these banks?

Marc: Well you can see that Capital One's a good test case because you can see that there’s been money with a consumer credit card portfolio for 40 years. And it's been fairly predictable. The correlation with whether it's unemployment or the rate of change of unemployment has been very good. The transparency as an outsider through securitized 30-day delinquency rates is very, very high. So, you get an early look into how the portfolio is...

Andrew: Which they publish every month, if I'm remembering correctly.

Marc: Every month, middle of the month, 15th of the month. The flip side is where do they have problems? They've had this kind of funky acquired portfolios. They have had problems lending to lending and taxi medallions in New York. That was a business they inherited from North Fork. They had problems with oil and gas. Oil and gas portfolio when there was an energy crisis in 2015 out of Hibernia. Right now also North Fork, they've got a New York commercial real estate portfolio, which clearly the question marks around. And yet through all of these cycles that have affected specific sectors, specific geographies, the consumer, the very diversified consumer credit card portfolio has kind of performed fine.

Andrew: Another question on Capital One. I've talked to lots of investors and I've talked to a few, a few who already considered Barry Sharp who were interested in Capital One even before Buffet bought it. And we can all just follow Buffet's investments and we probably shouldn't because they've all, I've like Apple and accidental over the past couple of years. Just the man is over 90. He might have made the most profit anyone's ever made in an investment off of Apple. It’s just unbelievable. But even before Buffett bought Capital One, they were interested in Capital One and there were lots of reasons. I think they were going to track the consumer focus Capital One's returns on equity. If you look over time have been fantastic all through 2022. The markets start selling them off because of worries about the consumer and the worries about autos. But one thing that I have heard is a lot of people like Capital One because of their online nature, maybe because they're still founder-led they think that they've got a massive tech advantage. And I just wanted to ask you, and I can give some anecdotes to that, I want to ask you, do you think Capital One does have tech marketing Advantage versus other people? Or is that a little bit of Capital One spin coming out do you think?

Marc: It's difficult to gauge marketing. Marketing is kind of in their DNA, they've always been good at that. They were one of the first banks to go into the cloud.

Andrew: That's part of what they say. And Capital One gives a thing where they're like 5 years ago if we had a 50 million bucket of loans that we realized was underperformed exploitation, we'd have to cut that whole 50 million out. But now, because we're cloud-enabled, we can look at that 50 million and say it's actually like the 10 million that we're lending to people who are named Mark with a C instead of Mark with a K. That's where it's going bad. So we'll cut that 10 million out. We can keep the other 40 million, which actually has good economics. And they've talked about other examples like that.

Marc: But then the flip side is they're big and they're old now. So there's a technical debt issue possibly. The example you gave is interesting because I was talking to an ex-CEO of Barclays in the UK not that long ago who left Barclays and now is involved in FinTech. And he says a lot of times the issue is the quality of the data. So, maybe in some registers, I am Mark with a K because it's misspelled in others, I'm Mark with a C. In others, I'm Mr. M. In others maybe it's a joint accountant with my wife and the systems aren't able to recognize that it's all the same person, all the same risk. So that's an issue. I can't, I can't answer that.

Andrew: You mentioned tech debt. Another argument I've heard for Capital One is because they were one of the first to the clouds and because they have done acquisitions, but probably not as many massive acquisitions as some of the, the argument is they've got less tech debt than other companies. You think about JP Morgan just this year, they buy first Republican, they're going to have a huge integration and they buy Walmart, all these companies are mismatches of multiple companies, and those integrations, they're never just always flipped onto one system. You build systems on top of each other and create this massive tech debt. And his argument was Capital One has much less tech debt than all of its peers. Do you believe that? Or do you think that might be a little...

Marc: Again, I don't know because I haven't looked at the tech, what I would say, and it is a feature that's common to both JP Morgan and Capital One is that profitability was really important because if you've got a free cash flow to invest back in tech, then it's a huge competitive advantage over an unprofitable bank. And again, to something we were talking about earlier to a smaller bank, if you've got both the profitability and the scale to maintain, JP Morgan in our investor day gave some very detailed disclosures on their tax spend. I can't remember the numbers off the top of my head, but a big chunk of it, 50% of it was maintenance. And then 50% of it was an investment. No, go ahead. Go ahead. And that's a big burden for an unprofitable smaller bank. So, certainly, just that ability to get 18% off credit cards, even though clearly the credit costs are higher, the average, return on assets at Capital One is sufficient to drive free cash flow to invest in tech.

Andrew: I think it was before the pandemic, it might have been just after, but I remember it was an article in the Wall Street Journal, it was talking about the death of community banks and how this tech debt we're talking about really catches up to them because JP Morgan's mobile app, it doesn't have problems. Sure. But it's probably much better than your local banks because if your bank manages a billion dollars of assets, they don't even have the budget to go and develop a really functional app. It was like the CEO of the local bank and he was like, yeah, I do most of my banking with Bank of America because their app is so easy and, and it just always stuck with me.

People who read my writing, people know I've said it, I'm really interested in the bank sector right now, and I look at all these banks and the answer might just be, why go buy the local community bank for 90% of book value when Capital One probably trades for 1.1 times book value. But guess what? As we said with the buffet, they are skating to where the puck is going. They have enough to invest in their technology, they're going to take all that share. Yeah, you're paying a little bit more for book value, but maybe you want to pay up a slight amount for a bank that's proven they can do 20% ROEs and they've got the tech spend and they’re probably pressed a little bit because they're making lots of text bend and marketing investment.

Marc: Yeah.

Andrew: We have gone through a lot. I do just want to ask Charles Schwab because I'm just fascinated by this company and what's happened with them. You had a great write-up. Again, I'll include that in the show notes. Charles Schwab has, fascinating history just as we sit here today. For those who don't know, Charles Schwab had the issue Mark mentioned earlier, they started a bank to fund their business. It went great, then all of a sudden everybody pulled everything from the cash Swiss, and now Charles Schwab's kind of influx, they were using the bank to fund the whole business because they went to zero on trading and all this sort of stuff. What do you think the future looks like for Charles Schwab? Is this a one-time thing or do they really need to reevaluate a lot of their business model?

Marc: I think that'll be fine. Maybe three things to talk about. One is liquidity, two is solvency, and then three is a kind of business mix. On liquidity. They're fine. They've got sufficient liquidity be it cash directly on the balance sheet or access to cash from the federal home loan banks, or the ability to sell some of their securities portfolios that would any event mature within a year and therefore trades close to par in order to satisfy any kind of extreme deposit outflow scenario. So that's fine. The company has given a lot of disclosure around that. The cost is thought of, and they call it cash sorting the process through which customers switch out of bank deposits into money market funds. And Schwab, unlike other banks, kind of sits as the gatekeeper to that. So unlike other banks, it gets the benefit of the custodian of the money market fund, and the salesperson of the money market fund gets some of the benefits from that switch.

Andrew: That's not small though, you don't get a lot for working with someone in the money market fund.

Marc: Yes, it's small. Its earnings drag very clearly because the earnings benefit of using those deposits where very little in the rate of interest is being paid in order to fund a securities portfolio, which is underwater but is still generating a few percentage points is much higher than the kind of few basis points they'll get from selling a mutual fund. But they keep the customer, the customer's not going. So there's some value there's some value in that. But it will cost them because right now wholesale funds are priced at about 5%, whether it's federal home loan banks or whether it's the new facility, which I don't think Schwab has tapped yet. But the new facility the bank BT FP program was launched by the Fed on the day Silicon Valley Bank went under. They've got access to... but it's expensive, so it's going to be a drag on their earnings. That much is clear.

I think we clearly underestimated cash sorting. Actually, most of it already happened last year. They came into this year and every month of this year, cash sorting has declined. It accelerated in March as a result of the factors we've spoken about the kind of crisis that ensued there, but it's essentially spoken about before. And then maybe the problem is that the sample size is very small in rising rate environments. We got 2018, 2019 and then before that, we've got to go back to kind of pre-crisis. The sample size is very small. Their bank is relatively new. And I guess it's natural to go to the most recent period because that's the most consistent with the customer's kind of mentality. And with the technology that we have available today, the ability to see what money market rates are and do switches and so on.

So back to that, they underestimated the impact, but more liquidity issue, a bit of an earnings issue. Where there is the question is this point about solvency because this is a brokerage business with a bank act. The bank is regulated but it's not regulated as a too-big-to-fail bank. There are four categories of bank category, 1, 2, 3, 4. One of the issues with Silicon Valley was that it was transitioning from one category to another and a lot kind of got lost in that process. But they don't have to include their available-for-sale mark to market as a negative to the extent it's a loss against their capital. And if that changes, then they'll take capital...

Andrew: Let me tell our listeners what that means. So, if you buy $10 of bonds available, if you buy them available for sale versus held to maturity $10 and they go to 5, if you buy them held to maturity, you keep marking them at 10 on your balance sheet. When you report your book value, you say our book value is $10 per share. If they go from 10 to 5 and they're available for sale, you report your book value as $5. So investors will see your book value as $5, but for regulatory capital purposes, you still report an available for sale as $10. So, what Mark’s referring to, and I'll do the numbers from memory, so they might be slightly off, but Charles Schwab reports 9% set one as their capital ratio, but if they're available for sale, were marked at their actual value, not their kind of cost. I think it would be under 4%, which would be well beneath a well-capitalized bank. So, they would maybe not get seized, but they'd need some pretty serious capital injections in some way shape, or form.

Marc: That's right. I think the numbers are 7.1 leverage ratio in March of 7.1%. But if you bake in really realize losses, the kind of $5 on that $10 to your example, you're down to 3.2% which is below 4%, but it's about cash. But the federal given runway, the market might not, we've seen in Europe certainly when there's a transition event, the market goes to fully loaded capital ratios very early. It's a very cash-generative business. The brokerage business isn't very capital-intensive. So, there are some margin loans but it's not very capital-intensive. So very cash-generative business. So, they can generate that very quickly.

Andrew: It's a cash-generative business. And the other point that all of these banks like to make is, the AOC so the difference between the 7 and 3 or 7 and 9% or whatever from your cost per available for sale, that accrues really quickly, Every quarter that ticks by, you get closer to those bonds paying off at par. So you create some of that back and that starts to [ Inaudible] quicker and quicker over time. I guess the one thing with Schwab, and we could talk a hundred different ways again, Mark did a really fascinating interview that involved, I didn't realize Bank of America bought Schwab and then Charles Schwab bought him back from Bank of America in one of the first private equity buyouts that involved cash flows, not asset management. It's a really fascinating event.

The one thing I get with Schwab and you can just like market psychology media the stock prices cost $55 per share as you and I are talking and it's down 33% so far this year and I thought like, hey, this is a good business. We can sort through all these different issues. You've got the bank and the brokerage, so in a disaster scenario, we can talk about split-offs and all this sort of stuff. I was like, this is going to be super cheap and I just go and look at it and I see 2022 earnings per share, $3 and 90 cents per share, 2021, $3 25 cents per share and just look at it. I'm like, that doesn't look like a distressed bank to me. It seems like a bank and there's going to be lower earnings going forward, but it's nowhere near distress to me. Especially 2 months ago people were, to me, talking about whether is he going to make it and the stock still trades at, call it 13 times, 14 times EPS. I'm like, it doesn't look like there's a distress to me. A has been my big issue. Tell me if I'm missing something or you can say I'm a little outside of my wheelhouse here.

Marc: I think you're right, I think the market, I think this is a degree of, I hate to say it, efficiency in the market, but I think the kind of, it's going to be okay, the case they're going to ride through it, it's an earnings issue rather than a liquidity issue or a solvency issue is the consensus and that's been reflected. There'll be short-term earnings hit, I don't know if that's 33%, and maybe its stock price simply reflects the downgrade in short-term earnings. I don't know. But the shop's going to be around and the TD deal is still going to generate synergies and everything's fine.

Andrew: And it's interesting you mentioned earnings issue, not liquidity issue. I'm surprised it took this. In March and April, I could not buy financial stocks because I thought there were real solvency issues. We didn't know how bad the deposits pullouts had gotten then all the banks reported earnings in April and I stopped being worried about solvency once all these banks came out and said we lost two or 3% of our deposits when Silicon Valley Bank bailed.

But it stopped right after that. But then the market freaked out in late April, early May as the First Republic went down and everything. And I feel like it started really pricing insolvency issues in May. And as you and I are speaking again, it's June 6th, I think the market's just starting to transition from these banks are going to be okay. You know, the KRE, the regional bank index probably 20% over the past week and a half or so. I think we're transitioning from, it's no longer liquidity worry or solvency worry anymore. Now we're starting to worry about what the earnings look like going forward. I don't know if you want to comment on that or anything.

Marc: I think that's right. I think there are other questions that mean that maybe peak multiple won't be as high as prior peaks. Some of which we've talked about. Just the notion that we have to think about what the duration of the deposit is. Once again, the idea that governments can just step in as a shareholder there is an argument that, and actually Buffet kind of declines this argument, but there is an argument that Juan[?] doesn't own banks and rents them. Maybe the cyclical aspect, maybe even Buffet would agree given what happened to Wells Fargo. I don't know.

Andrew: That's another one. The reason I didn't invest in banks for a long time was for years everyone would say Wells Fargo's the best culture and it turned out that for multiple years they actually had the worst culture. Last question on banks and because you are generous with your time, we're running out. Right now, I do think the market's transitioned to an earning story and we're going to have a consumer, we're probably going to have a recession coming at some point in the next year or 2. Yes. The regulatory burden's probably going up maybe we get some capital changes, but I do wonder if people have it wrong.

The First Republic and Silicon Valley Bank are gone and they were probably taking the super-prime creditors by wildly mispricing risk. You've had two of the top 20 banks in the world go away. We're going to have probably increased regulatory, specifically capital requirements going forward. I wonder if people are actually underestimating how profitable banks will be coming out of the heels of this, right? Like banks retrenching. I wonder if you're actually going to see loan spreads getting really juicy and banks actually 2 years from now, we look back and say they are actually a little inflated for the next couple of years because people priced the environment for much worse than it was.

Marc: Yeah, it could be. There's no capacity. There's a lack of understanding of how banks work. This idea that banks have to pay the idea that sort of wrong with a bank paying to depositors below what the market rate is. Well, that's how banks get paid. They won't send you an invoice once a month. You order a subscription contract with a bank. You pay by taking a below-market rate on your deposits. So since various fees in the aftermath of Dodd-Frank, various fees, late fees for example overdraft fees, all these have been `heavily regulated. All the more reason for banks to, call it a deposit beater for that to be a relatively low number.

Competition for deposits will change that going forward. The one thing you haven't mentioned, which I think could be really interesting for the sector is the distance to mediation threat to the sector overall is the Fed. The Fed, the RRP, which the Fed offers money market funds is a disruptive threat to bank deposits. And various bankers led inevitably by Jamie Diamond at JP Morgan have questioned why the RRP rate has to be fixed so high. And one thing the Fed didn't do in March or subsequently in May after the First Republic is changing that, but it's something that could happen. And if that happens, it kind of reduces the disruptive threat that the Fed poses through the RRP to the banking system, and therefore deposits will flow because money market funds, by the way, are themselves a threat to deposits because the money market stays in the banking system. The only way out of the banking system is into the Fed through the RRP. So, any legislative, well it wouldn't be legislative, any regulatory change there would be something to look out for, that could be a positive.

Andrew: Completely makes sense man, there was so much more to talk about. It's just a super interesting question. It's just been on fire the past couple of months. Obviously, the financial sector has been interesting. But the Schwab piece, the Capital Ones piece, you had the piece on JP Morgan's Investor Day, I'm sure I'm forgetting more because I've only got those three pieces pulled up, but it's just on fire. So I'll include links to all those in the show notes. Mark, this has been great. Thanks so much for coming on and we'll have to do a follow-up quicker than we got this one on.

Marc: Thanks Andrew, it's always a pleasure.

Andrew: Thank you.

[END]

Appreciate this interview and the content - good stuff. But the quality of this transcript is horrific!! Maybe check out another service provider who can do a better job?