Welcome to part #2 of my Tegus sponsored deep dive into the offshore space. You can find part #1 of the deep dive here; I’ll refer you to that post for more background on why I’m interested in the space, the aims for the deep dive, etc. This post is part the sixth entry in my deep dives sponsored by Tegus series, where every other month Tegus gives me a few expert interviews to dive into an industry (with the hope the resulting posts drive publicity to Tegus / shows how the platform can be used to get up to speed on fundamental investments. So please check out Tegus if you haven’t done so already!)

There are three key points to the offshore bull thesis today. In part #1, I covered bull thesis point #1 (days rates are set to keep rising). In today’s post, I’m going to cover point #2 (no looming supply or demand response to rising rates / tight utilization) and point #3 (even without continued rising rates, offshore is cheap on current earnings / rates). Point #3 is the most important part to me personally, but without points #1 and #2 it’s tough establish….

So let’s dive right in to point #2 (and I’ll admit I may have gone a little too crazy with this one). (editor’s note: a few days after publishing this part, I posted part #3 addressing the bull thesis and some Q&A on the series; you can find it here).

Thesis point #2: No supply left / supply response to be muted for years / no demand destruction

A famous saying in finance is, “The cure for high prices is high prices.”

High prices “cure” themselves in two ways: demand destruction and new supply. Consider:

High prices create demand destruction. If gasoline costs $1/galloon, you probably don’t think twice about driving. But if gasoline costs $10/galloon, maybe you decided to skip the cross country road trip. Maybe you start biking to the gym instead of driving. Maybe you sell your gas powered lawn mower and replace it with an electric one.

High prices incentivize new supply. If oil is priced at $25/barrel, there aren’t many economic oil fields in the world. The cost of drilling for oil would cost more than the revenue it would produce (i.e. it would cost more than $25/barrel to drill that oil); at those prices there’s basically no incentive to look for new oil. The world can operate on low cost sources it already has in place. But when oil goes up to $60/barrel, suddenly looking for new supply makes sense and a lot more wells are economic! And when oil spikes above $100, lots of higher cost plays are economic and make sense for drilling! Ecological concerns aside, nobody is thinking about drilling for oil in the Arctic if oil is $40/barrel. Spike oil up to $100 and suddenly it looks a lot more attractive (here’s an old article that put the cost of Artic drilling at ~$75/barrel)!

In comparison to the past ~5 years, the prices for all things offshore is high…. but a key crux of the real offshore bull thesis is that we are not even close to the offshore price levels that would incentivize demand destruction or new supply to come online.

Let’s start with the new supply side.

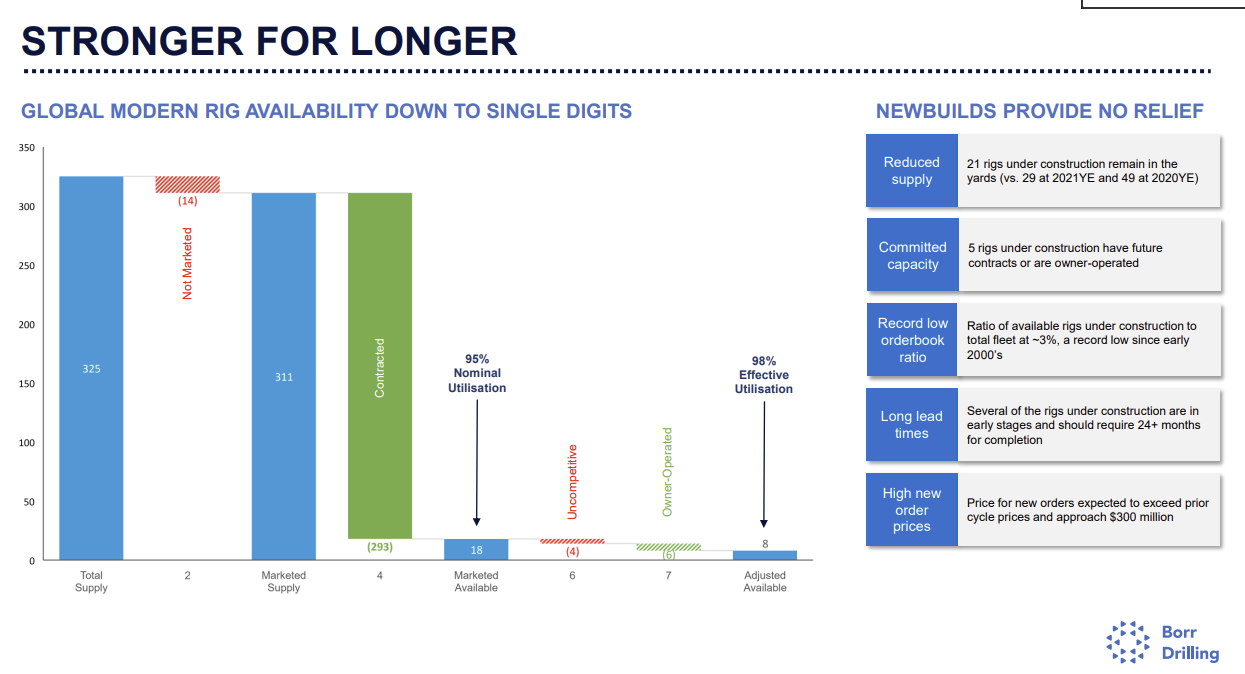

As I’ll try to show, the “no new supply” thesis can get pretty wild…. but at its base form it’s pretty simple. It’s this chart (from BORR’s investor deck).

Just to explain that chart and the overall supply picture a little deeper: The first place new supply in offshore generally comes from is cold stacked vehicles. I showed in point #1 that most of the cold stacked supply has generally already come online. The remaining cold stack supply that has not come online is generally the oldest, most outdated, smallest vessels left. Many industry observers suspect that a lot of that supply is so old and outdated that it will simply never return, and even if it did the shadow supply is so small that it doesn’t really budge the overall supply needle. As one expert put it,

imagine leaving your car for like six years in the driveway and then hoping it will restart. Yes, it might, it should, probably. But this is, whatever, $50,000 car, $100,000 car, it's not that complicated. Here, we're talking about stuff that takes two years to be built and that is extremely sensitive…. I looked at every competitor to assess how they were mothballing their equipment. And there was a pretty good split between people who had to pay $30,000 a day just to make sure it can be reactivated one day. And the other half, well, frankly, they were spending almost nothing, and the equipment was as good as dead..

Without cold-stacked vehicles to come online, the industry needs to turn to new build vehicles for new supply. Building an offshore vehicle is a massive investment: these cost tens (or, in the case of brand new drill ships, hundreds) of millions of dollars and several years to produce a vehicle. If you went out and ordered a new vehicle today and everything went right, you’d be lucky to take delivery on it in early 2025…. and that’s on the OSV side. Drillships / rigs are even larger / more complicated, and would take more time; VAL estimated last year that if you went and ordered a new build now it wouldn’t hit the water until 2028/2029

There are no yard slots -- and quite frankly, it would take 3, 4, 5 years to actually get that rig on water and to make the decisions to say we're going to have a rig that comes on to water and 2028, 2029 and in order to generate a return needs to work all the way through its useful life for the next 30 years. I just don't think any rational (inaudible) is going to be a decision.

Given that length of production, new build vehicles can come from two places: in the short term (i.e. <1 year), you can get new build vehicles from already ordered vehicles that are already under construction getting completed and delivered. In the medium and long term, you can go and order a new vehicle and take delivery a couple of years down the road.

The short term is actually pretty simple to discuss / figure out: the number of vehicles that are sitting around waiting to be finished is negligible. Remember, it takes at least two years for a vessel to be completed. If a vessel were going to get delivered today, someone would have had to place an order for it in late 2020…. at the depths of the COVID crisis… or earlier. I can promise you no one was ordering new builds during COVID when spot oil prices were touching negative numbers!

Zooming out, offshore oil has been in a “bust” cycle since ~2015. Basically no one has ordered a ship since then (here’s an article on the state of newbuilds that notes in total five rigs have been ordered since 2016). There are a couple of half finished ships / rigs that were maybe ordering during the last boom cycle, never got finished (the customer went bankrupt and stopped paying the shipyard or the shipyard just paused construction), and are now sitting at a shipyard half-built / waiting to be finished, but there’s simply not a meaningful supply of half-built ships or rigs that can suddenly be completed and come online in time to impact the supply picture for the next few years.

So we’re likely fixed on supply in the near term. In the medium and long term, we can go out and build new ships to meet rising demand….. but the beauty of the offshore thesis is that even after the big recent rise in rates we probably still aren’t at a level that incentivizes new build. An expert put it bluntly:

Your only available supply is going to come from stacked rigs. That's it. Newbuilds are effectively out. Pricing on them is between $800 million to $1 billion, terrible payment terms. So all the things that made newbuild attractive 10 years ago, every single dynamic of those is gone.

Remember, building a ship costs tens or hundreds of millions of dollars, and these are multi-decade assets. If you assume everyone in the industry is a rational and economic actor (perhaps a bold assumption!), anyone who is thinking about buying a new ship is going to bust out excel and pencil out an average earnings level / day rate for the ship over its economic level, figure out their cost of capital, and use the combination of the two of those to figure out the NPV of a vessel. If the NPV is more than the cost of the vessel, the industry will go out and build new vessels. If the NPV is below the cost of the vessel, the industry will not order vessels.

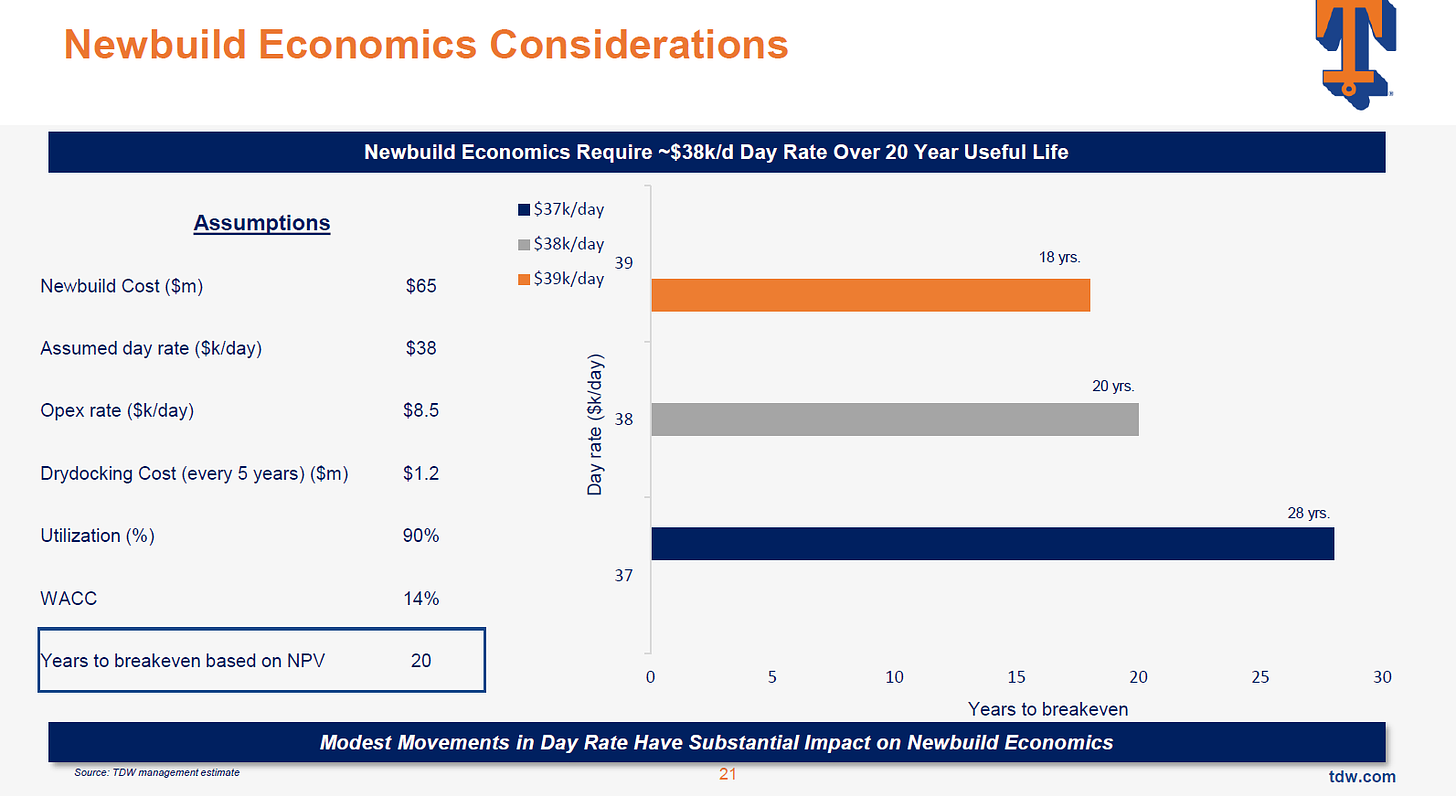

On the OSV side, TDW provides that math for you. They argue that a newbuild ship needs average day rates of ~$38k/day in order to incentivize newbuild:

Now, there are a lot of assumptions in that slide. As far I know, no one has tried to build a new OSV in several years, so maybe a new OSV would actually cost “only” $50m! Or maybe it would cost $80m! Who knows? Or maybe some industry participant has some type of sponsor support and their WACC is actually 10% instead of 14%, or they underwrite boats to a 25 or 30 year useful life instead of a 20 year useful life.

So you can quibble with a lot of assumptions in that slide…. but overall, I think they’re in the realm of reasonableness.

Here’s where things start to get exciting: If you listen to TDW’s most recent earnings call, the most recent day rates for large boats have just started to eclipse $30k/day. In other words, even after the massive upswing in day rates, we’re well below the rates that would be required to incentivize newbuild boats. (Note that I’ve focused on OSV’s simply because Tidewater lays out the math so clearly, but the math works just as well for offshore rigs too. One expert suggested to me that building a drillship today would cost ~$750m, and that the “general kind of rule of thumb that the offshore drilling space used is for every $1 million of build costs you need $1,000 of day rate. So you'd be looking at $750,000 day rate” to incentivize newbuild with a $750m starting cost. Given we’re currently getting ~$400k day rates, I’d say we have a long, long way to run before new drillships are getting built!).

That’s the bull thesis for offshore in a nutshell: at current rate pricing, these companies / assets are gushing cash flow versus their implied stock / market values…. yet we’re still far from a rate level that would start to incentivize newbuild economics! Rates need to go up further for that to happen, which will drive cash flow even higher, and these things will be gushing so much cash that the market will be forced to respond by rerating the stocks.

But the bull thesis on the supply side might be even better then it seems at first blush in two ways.

There’s the “terminal value / lifespan” question. Again, these assets need to be amortized over a useful life of 20+ years…. but, if you’re building a new asset today, you have to have a massive question about the second decade of their useful life (in the 2030s and 2040s) just given the political environment. Will offshore drilling be allowed in ten years? What type of energy will boats be required to run on in ten years (if you buy a boat that operates on fossil fuels and there’s a government decree that boats needs to be electric in ten years, your boat is suddenly a lot less in demand and might only be worth scrap or need wildly expensive upgrades….)? Maybe those questions seem silly…. but when you’re writing a >$50m check for an asset that you need to amortize over 20 years, a few small chances of your asset being worth 0 in years 10-20 can really impact your thinking and increase the near term earnings required to justify the investment (i.e. require higher day rates upfront for you to feel comfortable making the investment). As one expert put it:

I'd never say never, but right now, there is no way to justify it. There's no interested capital. Now in five years, if nothing changes, continue to work well, the drilling contractors are spitting out dividends, cash flows are healthy, and people are looking at five-year plus contracts, 10-year contracts than you may.

There’s the question of how quickly a boat could be brought on. This requires a little industry history. In the last boom in ~2012, offshore players ordered literally hundreds of boats from shipyards. When the cycle went bust, many of the offshore people went bankrupt. Shipyards were often left holding the bag on half finished vessels; the company that had guaranteed payment was insolvent, and the market was flooded with excess supply. Many of the shipyards faced insolvency too. Eventually, those boats got finished, and shipyards generally moved to making vehicles that were more in-demand (whether it was container ships, oil tankers, etc.).

So let’s say someone wanted to build new OSVs or particularly drillships today. There’s an open question of if any shipyard could or would start building one.

Remember, it’s been years since these vessels have been built. That means a lot of the people who know how to build them have likely retired or forgotten how to build them, and the shipyards have been set up to build other things.

All of those are problems that can be overcome, but they take time, effort, and money (one expert suggested getting a shipyard to build a new offshore boat is technically doable but would be a “monumental challenge”).

If you went and asked a shipyard to build one offshore vessel today, they’d probably turn you down, even if you came with pretty good financing and a guaranteed contract on the back end. They don’t want to get burnt again, and they’re probably not set up to build an offshore vessel. It wouldn’t be worth the cost and effort for the shipyard to retool to build just one offshore vessel.

It’s going to take the shipyards getting several orders for multiple new ships to incentivize them to go out and hire the people with the skills to build these boats and position their assets to build these boats instead of something else.

Normally, if you ordered a boat, it would be ~2 years until the asset could be delivered. But given all of those shipyard dynamics, if you ordered a boat today, it would probably take significantly longer even if you could get a shipyard to take your contract.

Anyway, put the two together, and rates need to go a lot higher to incentivize new build. And, if and when rates do go higher, it’s probably going to take a lot longer for new ships to start getting built and delivered than most people are expecting.

It’s worth pausing here and calling out one other thing: the offshore industry is cyclical. Boom / bust phases leading to tight markets and oversupply is normal.

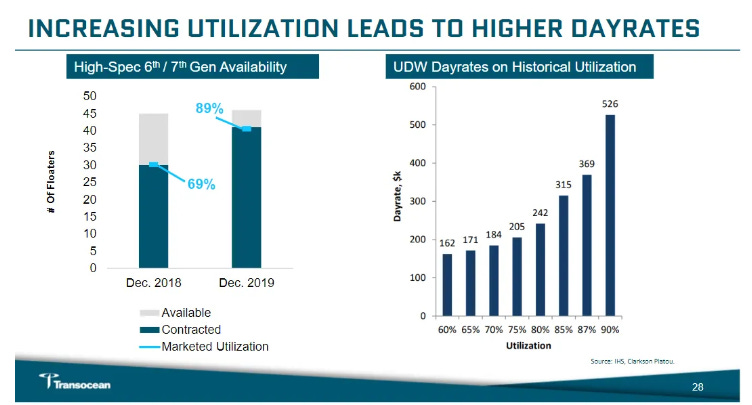

But it’s been a long time since the last boom market. If you look at vessel utilization rates, they were starting to tick up all through 2019 and into early 2020… only to be destroyed by COVID. Here’s a fun chart from RIG that argued the offshore market was starting to get tight that they published in Feb. 2020 (you’ll see this chart again in part #3 next week!).

The market getting tight and then crashing in COVID plays a lot into the current cycle we’re seeing. Remember, offshore is a cyclical business. You expect boom periods followed by bust periods…. but we’re seeing a “boom” cycle ~three years later than you would normally expect. Because of that increased length of time, we’ve had three years of extra aging on the global offshore market (remember, these are assets that last 25-30 years), so you’ve seen some extra assets retired. We’ve had three more years of shipyards and workers forgetting how to operate these assets, three more years of investors being scared of these companies, etc.

I think all of that plays a little bit into the “supply is a little tighter than it used to be” / “this cycle could be a little bit bigger than previous ones” trends.

Anyway, that covers why there’s likely to be limited supply response to meet the high prices. Let’s now turn to why there’s likely to be little demand response to higher offshore prices.

It’s actually pretty simple: demand responses involve some curtailing of demand (taking a bike instead of driving because of high gas prices)… but if it’s profitable to drill oil offshore, there’s simply not a ton of alternatives to hiring drill ships / supply vessels. If oil prices are high and it’s profitable to drill a well, you’re going to do that whether rigs costs $400k/day or $500k/day. If utilization on those assets is high, the limiting factors on rig rates are going to be the marginal profitability of wells (i.e. if oil is $50 and it costs $25 to operate a well, companies start bidding $25 to grab offshore vessels and rigs), and the main component of that is going to be what the cost of oil is!

Showing a company in action might illustrate this best. Talos (TALO) just bought a bunch of assets in the Gulf of Mexico.

Most of those are producing >50k barrels of oil equivalent a day. If oil’s ~$50, that’s >$2.5m in revenue every day. If Oil’s $65, that’s >$3.25m in revenue every day, and that increase in revenue is generally falling straight through to the bottom line. Lease operating expense for Talos is in the mid-teens/barrel (see p. 31), so that is very profitable revenue. If oil is at $65 or $70, Talos can economically bid quite a bit for offshore assets to make sure they keep pumping that low cost oil!

All of this is a big simplification as the demand side is circular and complex, but it directionally is painting the right story. If utilization remains elevated, what’s eventually going to put a cap on day rates is the marginal cost of production, and estimating that in large part depends on where you think the price of oil will be. If you think oil is going to $200/barrel, well then day rates are going up a hell of a lot because firms can bid an insane amount and still pump oil quite profitably. If you think oil is going to $40, firms can’t bid much because it isn’t super profitable to operate (plus, people probably get less interested in drilling and we go to an oversupplied market).

I can’t tell you where rates top out or where rates are going… but what I can tell you is where rates are right now. Transocean just announced a variety of contract awards and extensions, including an ultra-deepwater rig that got $43m for a 100-day contract ($430k/day) and a harsh semi-sub that got $34m for 110-days (~$310k/day). I don’t think we’re close to the utilization that would send rigs to the “take every marginal dollar from your customers” levels, but I just highlight those new contracts to show some very up to the minute contract pricing levels. We’ve had a lot of volatility in the oil market over the past few months, and even after a decent bit of price softening up to the minute contracts show that firms are still looking at their economics for drilling and saying it makes sense to keep going / paying those rates.

Discussing current rates is an artful way of bringing us to point #3…

Thesis point #3: Offshore is cheap / valuation undemanding even without rising rates

It seems like we’re on the cusp of sustained higher rates for offshore. Supply is tight and demand is rising. Rates have risen to the point where the underlying companies will spit off a lot of cash flow, but they’re still well below the levels that would start to incentivize new builds to bring on supply (and new build supply would take several years to deliver!).

It’s a bit of a goldilocks environment for a cycle: rates high enough to mint money, but not quite high enough to incentivize new supply.

That’s great…. but I think what really attracts investors (at least, what really attracts me!) to the offshore space is that the stock prices don’t appear to reflect the current day rate environment, much less the potential for rates to continue to rise. Let’s show that off by talking by trying to value these companies.

I’ve seen a bunch of ways to try to value offshore plays. I think the three best are:

Multiple of current earnings: simply take current day rates / earnings levels, and slap a multiple on those. Simple!

Multiple of earnings at a forecasted day rate: Figure out where you think day rates are going (whether that be to a mid-cycle day rate number, or a peak of cycle number), estimate an earnings level at that rate, and slap a multiple on it. Almost as simple!

Replacement value: Figure out how much it would cost to recreate a specific companies fleet / asset base, and use that to value them.

Each of these methods ties into the other in some way, and there are puts and takes to using each of those methods. Using current earnings makes you very susceptible to near term changes in day rates. Picking a forecasted day rate exposes you to bias risk (if you think energy is going way higher, you’ll always think day rates are going higher). Replacement value ignores what these assets can earn; the reason no one is building these assets is because day rates don’t incentivize them to build! To put it more simply: if you just built a rig for $100m, but day rates are in the tank and no one will put up the money to build a rig, is the rig really worth its $100m cost? Probably not!

But still, walking through each of those methods can help us triangulate a value base.

Let’s start with the simplest: Multiple of current earnings.

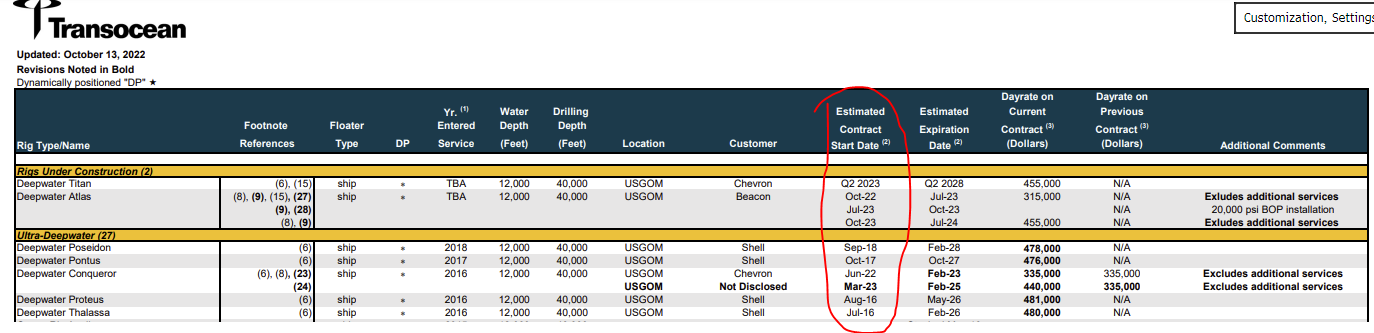

There is one complexity we need to consider here. Offshore players often utilize their assets by renting them out on very long term contracts. For example, Transocean (RIG) publishes a fleet update report every quarter (as do most companies in the industry). Unlike most of their peers, Transocean managed to stay out of bankruptcy because they signed a bunch of very long term contracts when rates were much higher during the last cycle. They still have a few rigs operating on those contracts (see below).

So when you’re valuing a company on current earnings, it raises the question: are you valuing them on the earnings they are currently reporting even though they might have a bunch of assets that are on long term contracts paying substantially more or less than current day rates? Or do you value all of them like their contracts instantly repriced to prevailing day rates?

Not an easy question to answer! And remember: rates can change quickly, so this can often be a moving target!

There’s no perfect answer here… but the best solution to the “what are companies currently earning?” question is probably just to look at TDW’s last quarter. They talked about it more on the podcast, but TDW thought the market was getting tight and has been deliberately chartering their boats out on shorter term contracts in order to take advantage of rising rates / tight supply demand dynamics. Per their Q3’22 call,

The average duration of the OSV contracts we entered into during the third quarter was approximately 4 months, which is indicative of our chartering strategy of going short from a contract duration perspective allowing us to continue to realize further upward pricing momentum in today's market.

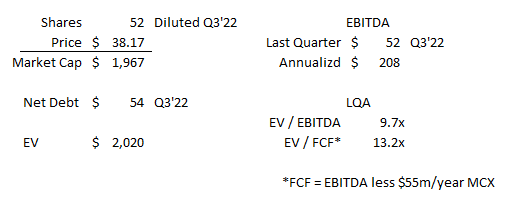

TDW earned $52m in EBITDA in Q3’22. They’re currently trading for a ~$2B EV / market cap, so if we annualized that $52m EBITDA number TDW is trading for <10x EV / EBITDA. Annualized MCX for the fleet should run at ~$55m, and taxes and interest should be minimal in the long run thanks to limited net debt (they do have some that will be refi’d in the next ~18 months, so there’s a little interest payments in the near term but it’s not worth splitting hairs over) and a lot of NOLs to shield them from tax payments, so FCF should come in at >$150m for a EV / FCF number of ~13.2x

It’s not the cheapest stock in the world…. but it would be hard to look at those numbers and say “dramatically overvalued! we need rates to skyrocket fast or else we’ll lose!”

So yes, it’s not a perfect valuation (particularly since rates rose throughout the quarter), but that’s one simple way to look at valuation using current earnings.

However, most investors prefer a different way. Rates were rising all through Q3’22 and into the new year, so even using the most recent reported quarter’s rates for a relatively open company like TDW probably understates the current level of earnings. Given how tight the market is, most investors I’ve seen prefer to take a day rate level, apply that to an entire company’s fleet, and say that’s the earnings level the company’s fleet is capable of.

Of course, there are two issues with that metric. First is it ignores that a lot of assets are under long term contracts at rates different than the level we discuss, and second is that it requires someone to assume a day rate price, which can introduce some bias based on your view of energy prices.

There’s no getting around the first issue, but for the second issue investors generally assume a day rate price of either the most recent going day rates or where rates were in the middle of the last cycle in the early 2010s.

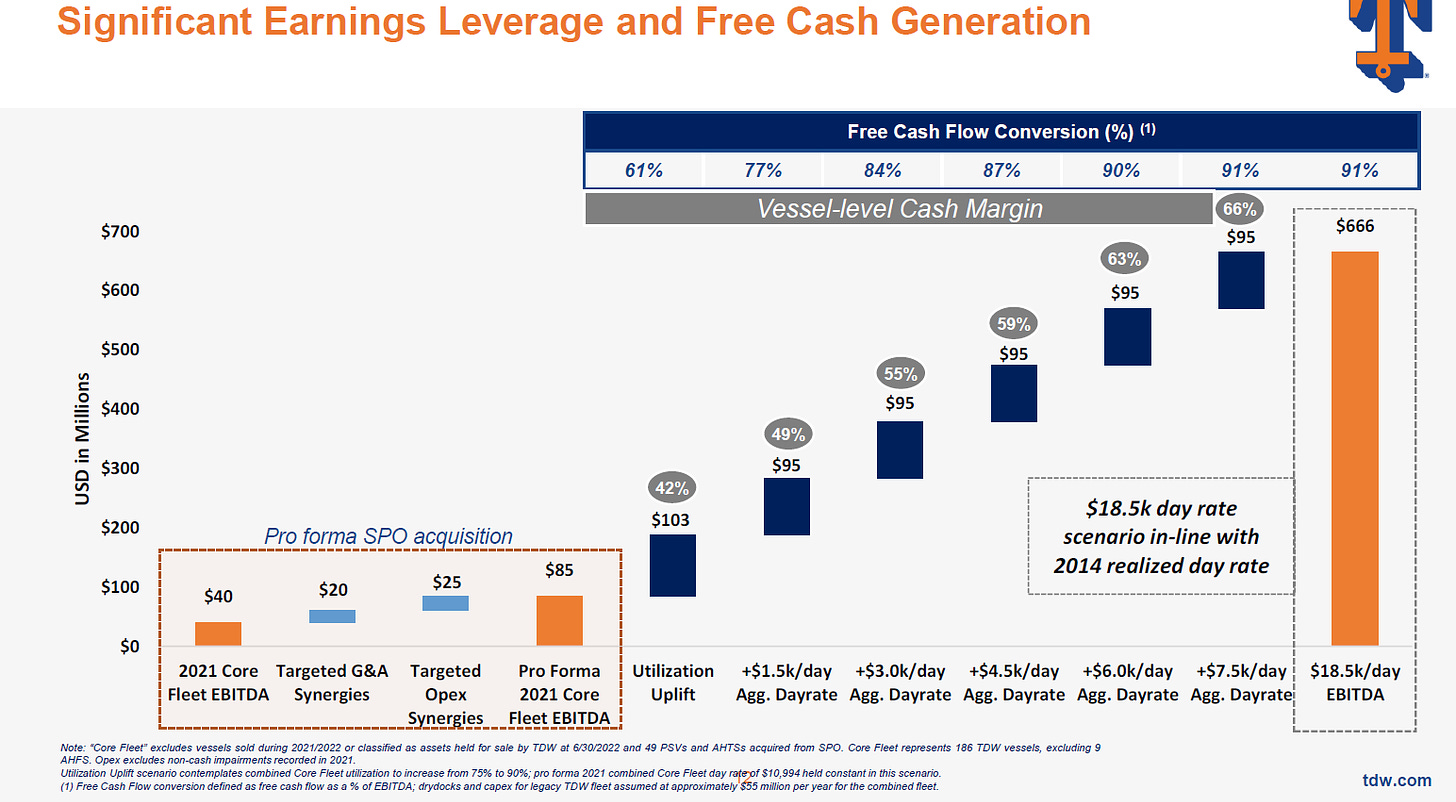

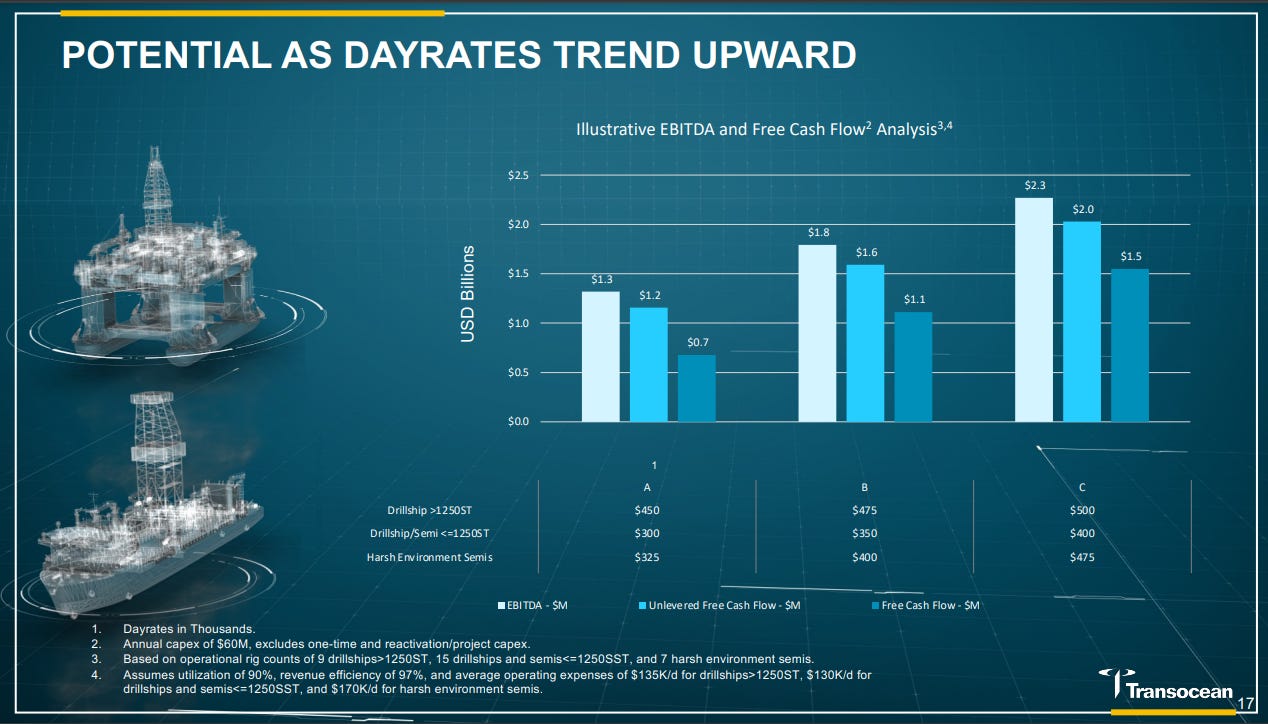

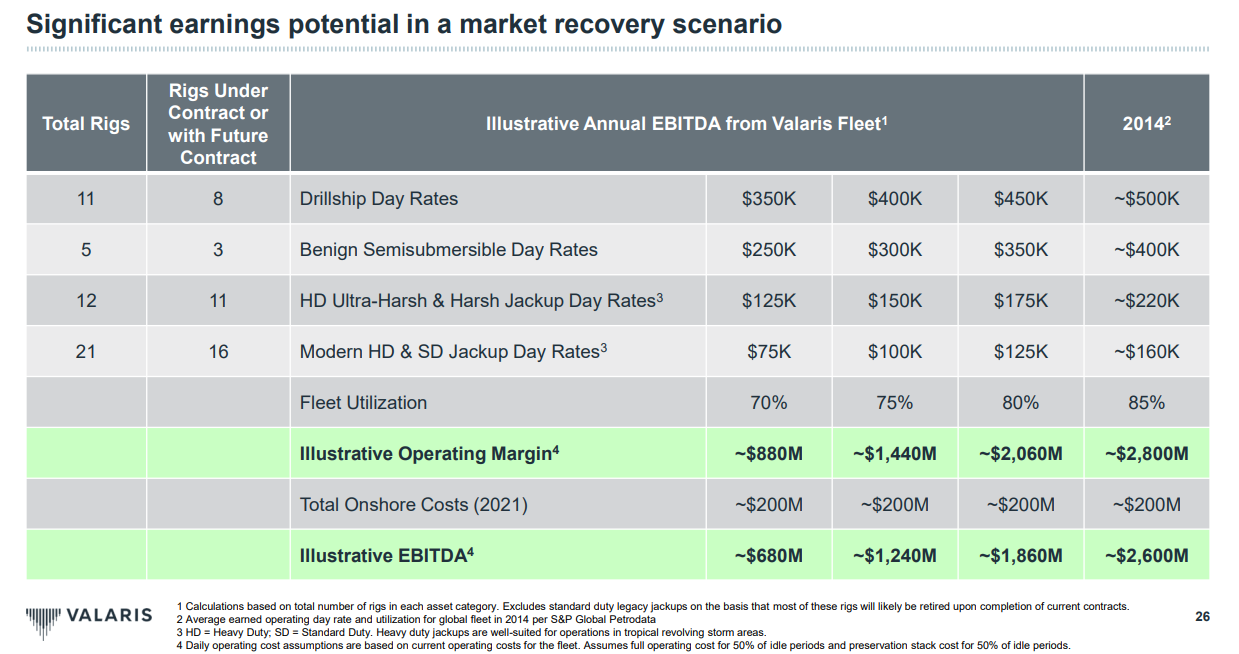

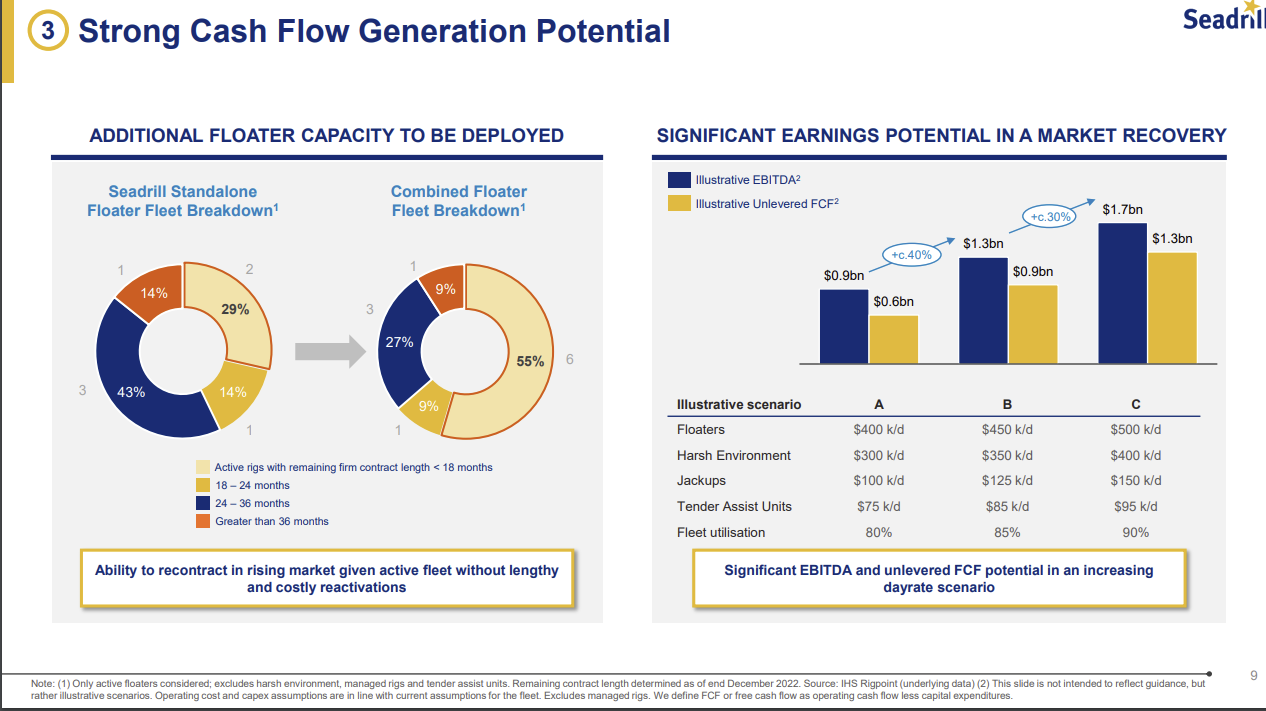

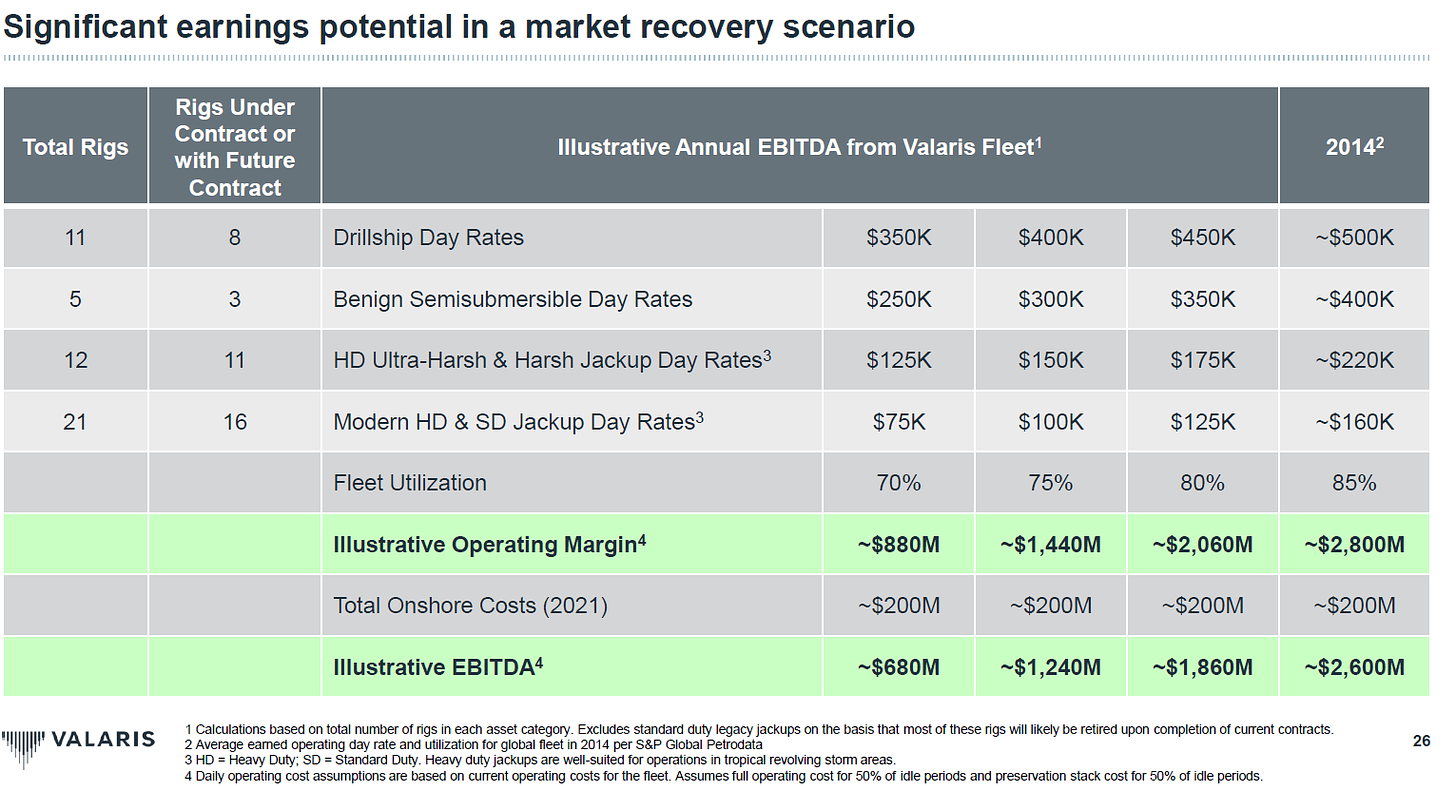

The companies are very happy to help you with this math because it makes them look quite cheap. Below I’ve pasted a slide from each of the most recent TDW, DO, RIG, VAL, and SDRL investor decks.

They’re all saying basically the same thing: if rates maintain around current levels / get back to 2014 levels, we are going to absolutely mint money.

As noted above, TDW’s EV is currently ~$2B. If you believe their earnings / rates number from the slide above, they’re trading for ~3x EBITDA at around current day rate levels. VAL, RIG, DO, and all of the offshore guys are trading for something roughly similar if you price their fleets around current day rates, though obviously all of them will take some time to roll their current fleet of their contracts struck at lower levels.

Those are very interesting numbers. At current day rates, EBITDA tracks reasonably well into free cash flow given most of these companies are unlevered, have net operating losses, and rates are high enough to drive very strong margins. So, generically, 3x EBITDA translates into something like 3.5x - 4.0x free cash flow to equity for these companies, which would mean they’d print their entire market cap in cash flows in ~four years.

Obviously that’s an eye catching number, but why is it interesting?

Remember in part #2 how I discussed that it would take at least 2 years to get an OSV online if you went out and ordered one today, and likely 4-5 years to get a drillship finished.

Buying these companies at ~3x EBITDA / 4x free cash flow is interesting because you could argue the companies will print their entire market cap in free cash flow before the earliest possible date a new vessel could be delivered to alleviate the supply issues! Obviously there are simplifications there (it assumes rates don’t go down, but it also assumes rates don’t go up!), but that’s a very interesting number….

One particular call out here: most of the industry filed for bankruptcy in the past few years and emerged with a relatively clean balance sheet. The only exception is RIG; they’re a ~$10B EV company with ~$6B in net debt. If you look at their slides, they paint a picture that could get them to >$1B in free cash flow (that’s cash flow to equity, i.e. after interest expenses). I just point that out because all of the offshore space looks cheap, but most of them have basically no debt thanks to past restructurings. I think the clean balance sheet stories are nice (it gives you time to see the cycle play out if a recession caused a temporary delay or something), but even after a big share price move for RIG you could pencil in a lot of upside if day rates keep moving higher given all of that leverage.

The last way to value these is a way I personally like the least, but there is definitely an valid argument for it (particularly if you think oil prices are going higher to drive some real competitive intensity / higher rates for the industry): valuing them at replacement cost.

The argument here is simple: just value everyone’s fleet / stock at what it would cost to recreate their assets today.

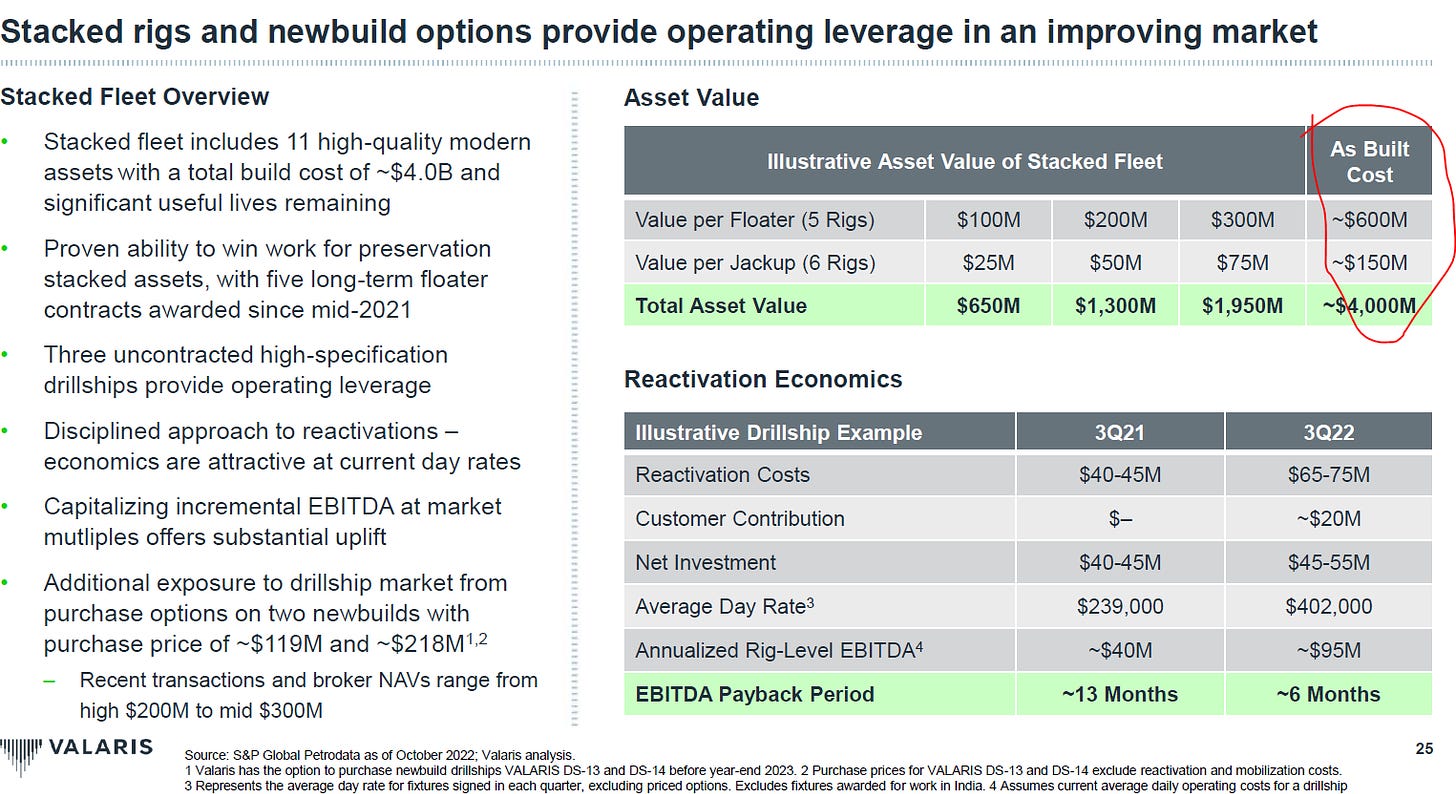

So let’s use VAL as an example. They have 11 drillships:

Earlier in the article I gave a bunch of quotes about how it would cost ~$700m to make a drillship today (if you could get a shipyard to do it!). The replacement cost valuation would value each drillship at the cost of a newbuild, so $700m * 11 drillships = $7.7B in drillship value.

Now, VAL’s drillships are aged. A drillship should have a useful life of ~25 years, and VAL’s are on average 8 years old. With 17 useful years remaining, you could say maybe you say they only worth ~2/3 (rounding 17/25 to 2/3!) of a newbuild. In that case, $700m * 11 drillships * 2/3 = ~$5.1B

Coincidentally, VAL’s EV as I write this is almost exactly $5.1B, so replacement value analysis would say that you are buying VAL’s 11 drillships at today’s prices and getting their other ~38 ships (all of which are worth hundreds of millions of dollars) as well as their ARO JV for free. VAL would have multi-multi-bagger potential upside on that valuation.

Another fun way to look at it that VAL likes to give? At Q3’22, VAL had 11 “stacked” assets that weren’t in service. At cost, those assets alone are worth $4B (using their numbers; I used a $700m value for a floater and they’re using $600m; I think the difference can be explained by wage / cost inflation, but it’s not really worth splitting hairs over). Again, VAL’s EV is about ~$5.1B right now, so at cost ~80% of VAL’s EV would be covered by their stacked fleet. VAL has 38 rigs operating, so you’d be paying pretty much nothing for their working assets (which, again, vastly outnumber their stacked assets!).

So why don’t I like that cost based analysis?

Simple: much of this article has focused on all of the reasons it doesn’t make sense to new build boats and rigs. Day rates are too low, and terminal value too questionable. I don’t think it makes sense to value these at replacement cost if we’re saying no one in their right mind would consider spending the money to replace them!

But I might be too pessimistic. People much sharper on the industry than me have told me this is how these should be valued, and, in general, investors tend to do well when they can buy things way below replacement cost, so that valuation certainly has to be considered when thinking about investing in the space.

Anyway, you can pick your poison: earnings at current rates, earning if rates keep rising, or replacement value. Either way, you’ll come to one conclusion: offshore assets are much too cheap… provided the offshore cycle doesn’t turn!

That’s a topic I’ll address in part #3 early next week (Update: that post is now live!). I look forward to seeing you then, and please remember to lob in questions / comments / thoughts on offshore in the mean time; I’ll try to address them in next week’s post.

Long time follower, always appreciate your sharp thinking. Unfortunately Mr. Market is not always logical and/or the financials deteriorate, and we miss the punt widely like with the broadcasters. etc.

I think you've nailed it with the offshore thesis, especially considering how few things are left that could go wrong. Folks should stand up and listen.

This was amazing! 🙌 👍🏻👍🏻👍🏻👍🏻👍🏻👍🏻