It’s been a rough few months for the stock market.

Now, it may come as a surprise to you that it’s been rough for the markets if you spend any time on fintwit; there’s certainly no one tweeting / bemoaning how tough it’s been out there recently (editor’s note: please read that sentence in your most sarcastic voice possible. Based on my feed, fintwit would have you believe the end times are here).

But it has been rough. It’s been a reasonably fast 10%+ sell down for the Russell since the beginning of September; even the S&P, with all of its “Magnificent 7” goodness, is down 6% since the beginning of September.

And this drawdown comes on the heels of a pretty brutal couple of years for small cap investors: the Russell is down ~25% over the past two years; the S&P is just below breakeven over the same time, so while the S&P is not setting anyone’s world on fire it’s certainly beating the pants off the Russell (and that’s just two years; as I tweeted out last night, the S&P has ~doubled the performance of the Russell over the past twenty years, and in turn the Nasdaq has more than doubled the performance of the S&P over the past twenty years. Wild!)!

Anyway, I don’t write all this to tell you that now is the time to pile into small caps, or that small caps are generationally cheap. There are plenty of people on fintwit to tell you that (though, yes, I probably do fall into the camp that believes these things come in cycles and small caps will outperform large pretty substantially over the next 10-20 years).

I wanted to write this post in a broader sense just to say that now is probably a pretty good time to be buying stocks. Doesn’t matter if you’re buying large cap, small cap, or international…. it’s a nice time to ignore the fear and buy stuff.

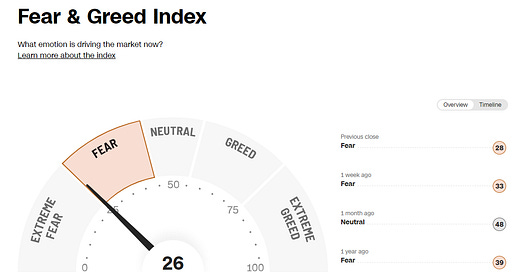

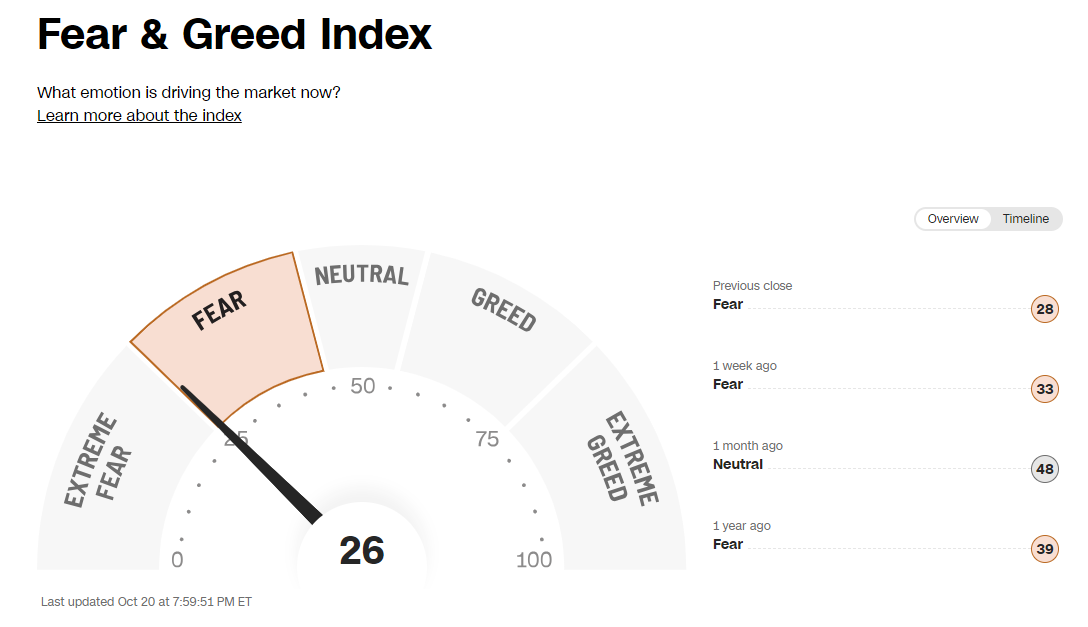

You’ll note I said “fear” in that paragraph. There is a heck of a lot of fear out there right now. The CNN “fear & greed” index is just on the cusp of extreme fear.

Interestingly, if you actually look at all of the components that make up the fear and greed index, all of them are well into “extreme fear” except for the junk bond spread. A sample below:

The CNN Fear & Greed index is obviously a silly little index, but I do like it because it’s such a quick / easy way to benchmark where the markets at.

And I understand why there’s so much fear out there. Two ongoing wars (Ukraine / Russia and the Middle East). Domestically, the House is self immolating, and while it makes for fun headlines, having the House effectively shut down is going to start having real world implications in the near future. Speaking of real world implications, the government continues to wrack up enormous deficits, and those will only get made worse by the incessant rise in interest rates. And the rise in interest rate is putting pressure on valuations; it’s a lot harder to justify a 100x sales multiple by pointing to future world domination when you’re discounting that future world domination at ~5% instead of 2%!

So yes, it’s easy to be bearish…. but bull markets always climb a wall of worry, and there’s plenty of worry out there.

But I particularly wanted to focus on one particular point: the rise in interest rates. A common thing you’ll hear from investors looking to be bearish is “interest rates have risen so much, and interest rates act as financial gravity. How can stocks not have more room to fall?” They’ll generally mean it in something like this: two years ago, the 10 year treasury was trading for 1.5%. Today, it’s ~4.9%. You can play with the math around that increase in a lot of ways, but the basic thought is that that large an increase in interest rates should have sent the S&P down a lot more than 6% it’s dropped.

Let me go on a quick tangent: in my prior life (before I was running the YAVB empire), I worked in consulting and private equity. At both, we would do modeling of companies to estimate their fundamental value. The modeling would inevitably involve discounting the company’s cash flows back to the present at some interest rate. I would get in fights with my bosses about what interest rate to use all the time: to make things simple, I generally wanted to use the ten year treasury rate plus some risk premium. My bosses, however, would always overrule me: they had a base “long term interest rate” number that we would plug into the models and then put an equity risk premium on top of that, and that base interest rate was substantially higher than the ten year treasury (or where the companies could borrow huge amounts of debt at). The reason they wanted to use a higher “base rate” interest rate was every deal looked way too cheap if you used the ten year rate as an interest rate; you’d have to assume a risk premium that was frankly insane to justify how low stock prices were with the ten year at that level.

So our debate was simple: I argued that the ten year was a number that was actually out there that companies could borrow against, and choosing a higher number out of the air because they didn’t like the valuation results the market interest rates gave didn’t make any sense. They’d argue you could not use the ten year number, because the stock market was not underwriting any stocks with interest rates anywhere near the ten year interest rate level. So you had to be practical and use a longer term normalized number. My response to that would generally be “exactly, all of these companies are way undervalued; there’s a massive arb for them to take out an insane amount of debt at low interest rates and buy back their stock or go private at a low multiple.”

With the benefit of hindsight, I think both of us were partly right: I was right that there was a divergence between the equity and debt markets; in general, companies that went private with huge leverage made huge profits (effectively, they arbed a much higher equity risk premium against a lower risk premium). But my bosses were right that you had to have some practicality; the stock market would have had a much better run over the best 10 years if I had been completely right, and by trying to underwrite using the ten year against what the market was clearly implying, I was making some type of bet that the market would self correct over my holding period (though, again, I thought there was a really arb between using really cheap debt to buy out stocks at low multiples!).

Anyway, to bring that little tangent back to the discussion of interest rates, there are a lot of reasons I think the market hasn’t sold off harder on the huge increase in interest rates (for example, ten year real rates are around 2.5% right now; that’s way up from a few years ago, when they were generally quite negative, but still pretty low in the grand scheme of things)…. but I think a major one is that the equity market never fully discounted how low interest rates were. A really large consumer staple like Coke (KO) is more bond proxy than equity; if it had ever fully internalized 1-2% 10 year treasuries and negative real yields, it would have traded for >100x EPS. Instead, it’s generally traded for a mid to high 20x multiple, which I wouldn’t call screamingly cheap but I’d also say is generally quite attractive versus a ten year rate approaching zero! You could do similar math for a variety of industries that are more stable / well developed / cash cow style businesses and see that their multiples never came close to the levels that they should have if they were really underwriting the prevailing ~0% interest rate environment.

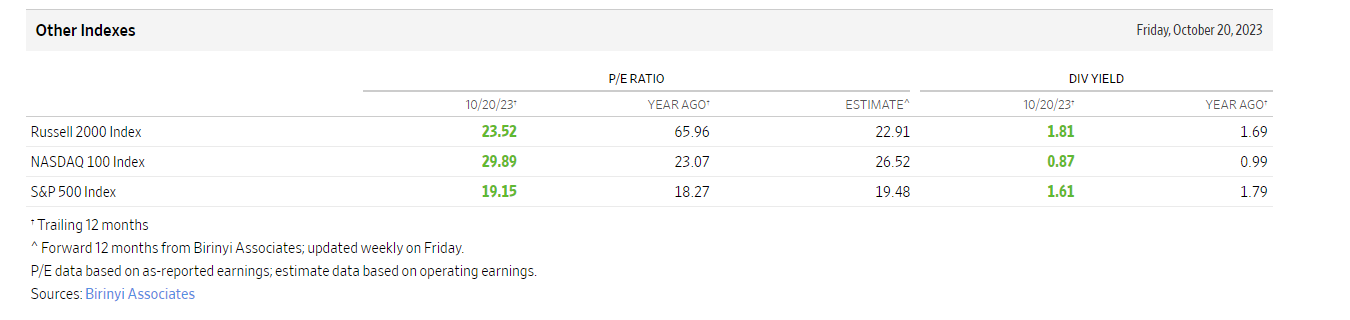

And I think you can see that in the overall averages. The S&P is currently trading for just under 20x P/E; I don’t think that’s a crazy number…. in fact, versus where interest rates are currently, I think you could argue it’s on the cheaper side.

That’s just the overall index! I think a lot of the “index multiple” is supported by some larger cap names that still trade for premium multiples. For example, Apple is the largest component of the index (>7%) and Bloomberg tells me they trade for ~28x P/E. MSFT is the second largest component (just shy of 7%) and Bloomberg has them at ~30x P/E. AMZN and NVDA are two other top five components (combined they make up >5% of the S&P), and they each trade for >50x P/E. Take those four out, and the overall index is probably trading 1-2x turns cheaper than it looks on a headline bases.

It seems most of the people I talk to today (and my twitter timeline!) alternate between despondent (“damn, I’m getting creamed; will stocks ever go up again?”) and fear-mongering (recession! inflation! interest rates!). I get it…. but the index overall looks cheap-ish, and once you dig past the largest names I think there’s real value to be found.

You pay a rosy price for a cheery outlook…. you certainly don’t have that today! I think investors willing to dig a little will be pretty happy with the outcomes a few years down the line.

PS- it’s recently come to my attention that the intensity of opening rates for YAVB are quite good, but I’ve done a poor job of asking for it to be shared around to help the blog grow. So if you like this post / blog, please don’t be scared to press the “share” button below to share it with a friend!

Eh historically speaking one will make more money over time being bullish. That said are things really cheap and the outlook rosy? I have my doubts. Lets not forget about the cold war with China which likely has more importance than both other conflicts combine. The national debt has surged (roughly 250k per worker..) of course that has never mattered, until one day it will. Treasuries are being dumped by the Fed, China, Russia, Japan, etc. Interest payments now exceed military spending and last I checked that was a big number. The woke hate oil, the SPR is at decades low and OPEC is actually keeping to quotas.

Useful perspective. Thanks for writing.