One rule that I’ve come to appreciate over time is that a consistent way to make small amounts of money is to bet on everything returning to their “base rate”, but often the path to real alpha is to identify an “inflection” where something has changed and the base rates no longer apply.

Ok, that’s a huge simplification and kind of a silly sentence, so let me use an example to illustrate what I’m trying to get at. Consider the auto industry; it is famously competitive, wildly capital intensive, and extremely cyclical. Because of all those difficulties, the average car company has historically traded for a pretty low (normalized) P/E multiple. For our purposes, let’s just say car companies generally trade for 8-10x P/E.

As an investor, you might use that to your advantage. You can estimate a normalized level of earnings, and use that as a benchmark. When an automaker you like trades for (say) 5x normalized earnings, you buy it because they’re too cheap, and when an automaker you don’t like trades for 15x normalized earnings, you short it as too expensive (this is purely a hypothetical! Shorting is risky; check out our disclaimer). So that “buy at 5x, short at 15x” rule of thumb is a wonderful way to make small amounts of alpha over time; in fact, a lot of long/short or quantitative shops employ those types of rules en masse (often with a heck of a lot of leverage) to generate enviable returns over the long run.

That rule of thumb works great in normal times….. but the real alpha can be made when those rules get broken.

So you might “know” you can generally make money by shorting auto companies at 15x earnings…. but if you applied that rule of thumb to Tesla (TSLA), you would have gotten your face ripped off. And plenty of people did! Here’s a very coherent short thesis for Tesla from 2016; Tesla’s a casual ~20x since then.

Tesla is obviously an extreme example and a single stock…. but “inflections” that break old rules and base rates can happen industry wide as well, and when they do there’s often an awful lot of money to be made.

Consider one of my favorite industries, cable. In the 1990s and 2000s, cable was mainly used to deliver video. Cable was a “meh” (though stable!) business; most of your revenue got eaten up by your suppliers (the ESPNs and ABCs of the world), and in a lot of markets you competed with satellite TV, who actually had a cost advantage as their larger (nationwide) scale let them negotiate better prices with suppliers. In that world, a simple rule of thumb was a cable company was worth ~8x EBITDA. Why? EBITDA margins ran ~30%, and capital intensity ran ~15% of sales. So if you bought a cable company for ~8x EBITDA, you were paying a fair multiple (~16x free cash flow) for a stable, low growth business. A good value investor would try to buy cable stocks when they were cheap at ~6-7x EBITDA and sell them when they were dear at ~9-10x EBITDA. If you were running long/short, you might even go crazy and start shorting when the cable stocks went over 9x EBITDA.

That started to change in the late 2000s and early 2010s. Suddenly, cable was used more to provide broadband. Broadband is a much higher margin business than video; in video, ESPN and ABC get a huge cut of every dollar, and there are no corresponding costs in broadband (the gross margin of providing broadband is ~95%; once the system is in place, you basically just need to pay for some electricity to deliver light down some fiber cables). Margins went way up; today CABO is pushing ~55% EBITDA margins and they could very well hit 60% in the near future! Broadband is also a much “moat-ier” business than video; satellite had some real advantages when it came to video, but they were drawing dead to the superior infrastructure of cable when it came to the ever rising need for speed / capacity that broadband presented.

So you had a sudden change where cable’s margins went up substantially and the business got better as they suddenly leapfrogged a competitor…. and that’s not to mention that the video business didn’t just go away, so the broadband business didn’t just increase margins but it also accelerated growth. So here you have a change that increases growth, increases free cash flow, and decreases competition intensity. That’s quite an inflection!

And that inflection presented opportunity for investors. If you understood what was happening, you knew cable stocks that were formerly fairly valued at 8x EBITDA were screaming cheap as they transitioned from video to broadband companies. Ignoring that broadband is a better business with more pricing power, more competitive advantages for cable, etc., if you just assumed a cable company was worth 16x free cash flow, as a video provider with ~30% EBITDA margins cable was worth ~8x EBITDA….. but as a pureplay broadband company with 50% EBITDA margins the same cable company is worth ~10.5x EBITDA. The business had completely changed; if you didn’t understand that change, you might be tempted to short cable companies when they went from 8x EBITDA to 9x EBITDA….. only to have your face ripped off as they traded up to 10-12x EBITDA (remember, cable companies run with multiple turns of leverage, so going from 9x EBITDA to 11x EBITDA could involve the stock going up by ~30-40% on multiple alone, and that’s before adding accelerating growth and the like!).*

As with so much of investing, the GOAT of recognizing late stage industry change is almost certainly Buffett. It’s hard enough to recognize these shifts at a company level (though Buffett successfully did that with Apple in the mid-2010s, and it created one of the most lucrative investments of all time), but Buffett has done it twice on the industry level: with railroads and airlines.

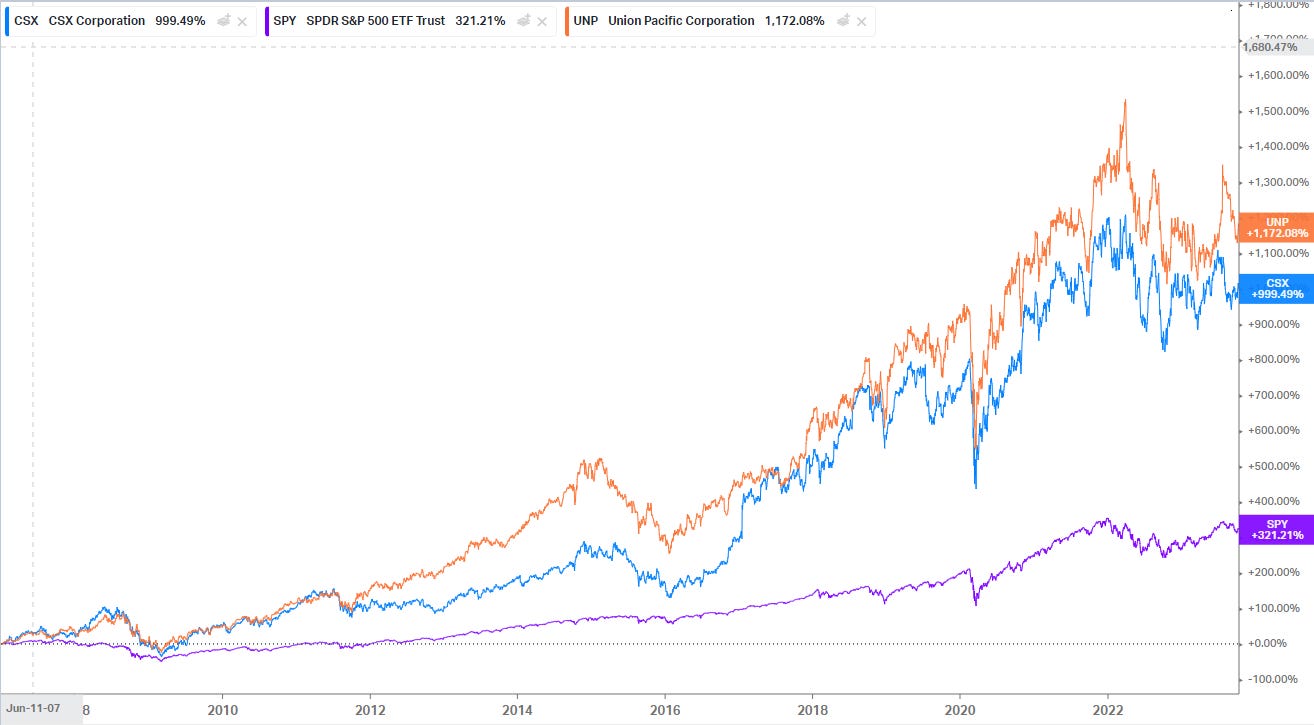

Let’s start by looking at Buffett’s more successful of the two: his investment in railroads. Railroads were “left for dead” in the 60s and 70s, and most investors wouldn’t touch them for the next few decades. After having been burnt, investors came to view railroads as capital intensive, cyclical business that were always on the verge of distress and where powerful labor unions could suck out any fleeting profits…. but, in the early 2000s, Buffett recognized that deregulation and decades of consolidation had left railroads as oligopolies that were a direct play on American economic growth with a cost advantage over substitute transportation (like trucking) thanks to rising energy prices. Buffett first bought BNSF stock in early 2007, and in late 2009 he offered (and subsequently did) buy the whole company. Given Buffett took the whole company private, we can’t track exactly how well that investment did….. but if you look at the returns of UNP and CSX (two railroad peers), it’s pretty safe to assume the BNSF investment / acquisition has been a home run.

The other “industry inflection” Buffett has called recently was in airlines. As late as 2013, Buffett was calling the airline business a “death trap” for investors. But he bought huge stakes in airlines in mid-2016 when he realized the industry had consolidated into an oligopoly and that things like loyalty programs and reward miles would continue to benefit larger players and provide profits through the cycle. I’d probably give Buffett an incomplete on this one; I personally think his thesis would have worked out…. if not for COVID. The world changed when COVID hit, and there was no industry more affected than the airlines. Buffett did dumped most of his airlines in COVID, and so you could look at the results and say “what an awful investment….” but I do think Buffett saw and called the industry inflection and just got very unlucky with this one.

I think the common thread in those investments is obvious: Buffett saw a business and industry that investors had always viewed as capital intensive and cyclical…. but he realized the business had consolidated down to an oligopoly, and that it would be very difficult for new players to enter the industry going forward (for railroads, because no one can build a new railroad today; for airlines, because loyalty programs and credit card miles give huge advantages to incumbents / larger players). Buffett saw whole industries priced as commodity / cyclical companies, and he invested in them on the expectation they had evolved into oligopolies and would realize corresponding benefits over time (both from a higher multiple and from better earnings over time).

Again, none of this is crazy controversial. I’m basically saying “alpha is generated when you (correctly) recognize that something has changed before the market has.”

Or, to simplify even further, I’m saying “find an inflection, invest in it early, and you’ve got a great chance of generating alpha.”

So why am I mentioning “inflection” investing?

I think we’re at an “inflection” point when it comes to antitrust enforcement and merger arb investing…. but that’s a topic for tomorrow’s article. See ya then!

*Just a note: all of this was, of course, a simplification for the purposes of this article. Directionally, everything here is 100% correct, but I’m sure I’ll get a few emails saying “cable companies averaged 7x EBITDA, not 8x, in the 90s!” or “car companies should trade for 12x, not 10x!” I’d be tempted to respond to the later by noting that, excluding Tesla, car companies today would be popping bottles if they could grab even a 5x multiple, but I digress. Anyway, investing is complex, so yes, the stories here are somewhat simplified, but directionally they’re on the money so no need to correct on slight discrepancies!

Lots to think about. Thank you! I'm wondering why Buffet isn't re-entering the big four airlines now that COVID is behind us and they're still valued cheaper than when he bought.

Buffet did it in the 1970’s with newspapers .