A… Journal of Accountancy editorial complained that depreciation has become a tool used by management to counter fluctuations in profits. Good year had been made to bear heavy charges. Bad years bore no provision or an inadequate one.

If I told you that quote / editorial was from an editorial discussing adjusted EBITDA today, that probably wouldn’t surprise you. In fact, it probably wouldn’t surprise you if that quote formed the basis for a short seller report revealing how a shady company had been gaming their accounting to look more profitable to lure investors in.

But that quote (from More Than a Numbers Game: A Brief History of Accounting) isn’t about adjusted EBITDA or shorting a company. In fact, the quote isn’t even from this century. I used the ellipsis to hide that the Journal of Accountancy the quote came from was released in 1912.

Why do I bring the quote up?

I’ve really been into reading historical books on investing recently, and it’s really striking how much you can see the parallels between things that happened a hundred years ago and things that are happening today. In fact, you’ll often see trends and parallels in the past that were much bigger than anything we can imagine today. For example, consider AI. Unbelievable sums of money are being spent on the AI race, headlined by Microsoft’s announcement they’ll spend $80B on data-center AI in 2025. To put that $80B into perspective, it’s more than the market cap of Mondelez, which is company #120 in the S&P 500. So in one year MSFT will spend more in capex than all but the top ~120 businesses in the U.S. are worth.

But not only is their precedent for that spending, MSFT’s spend actually pales in comparison to some historical spend. More Than a Numbers Game notes that railroad infrastructure absorbed ~40% of American economic output in 1880. U.S. GDP is >$27T, so in today’s terms we’d need to see ~$11 trillion in investment to match the railroads in the 1990s.1

There are plenty of other examples in the book. Just to stick with railroads, the book notes that as the 1800s progressed and the markets got a little more frothy, investors were buying railroad securities not based on financials (in part because in the 1800s they didn’t have financials) but largely based on confidence in the investment bankers! You could draw a hundred parallels between that anecdote and markets today, but I think the best comparison would be the dotcom bubble when people would buy hot IPOs or securities purely on a sell side recommendation. Later, the book notes management teams would use dividends and return of capital to fool investors, who might mistake a dividend that was a return of capital for a dividend that was a return of profit and a sign the business was doing well2. Again, the parallels to the present are uncanny…. every decade there is a company that pays out high dividends to pull the wool over investors’ (particularly retail investors’) eyes. “Of course the company is doing well, they pay out a 12% dividend” the investors well say, ignoring that the company is raising enormous amounts of capital to cover the dividend while the core business is often imploding.

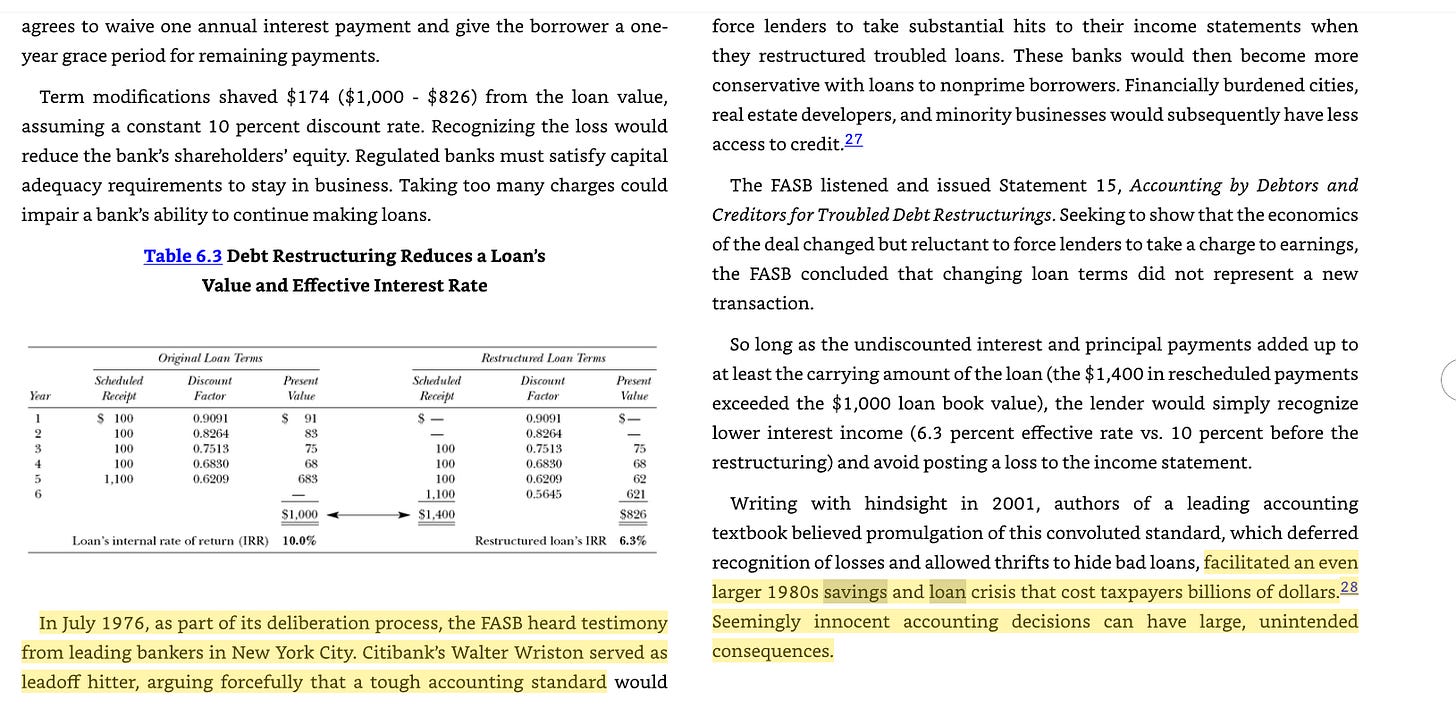

Perhaps my favorite example in the book comes in chapter 6 (and again chapter 9), when financial institutions lobby FASB to let them report loans at par even if they have credit issues…. which paves the way for the 1980s savings and loans crisis. I love that example so much because it rhymes so well with the “held to maturity” SIVB / First Republic blow ups.

Those modern day parallels are what I like so much about reading the books. It’s incredible how finance seems to work on cycles, and every modern bubble has historical parallels.

But here’s what I’ve been thinking about: in hindsight, it’s always easy to match a trend with a historical analogy. You read about the Great Beanie Baby Bubble, and it’s not hard to draw a straight line to Tulip Mania. The similarities between the late 20s leading into the Depression and the mid-2000s leading to the GFC are uncanny.

The question I’ve had is how practical those comparisons are in real time. There’s the old joke that economists have successfully called nine of the last five recessions; I wonder if the historical parallels fits really nicely with hindsight bias but if you try to use it in real time you’ll end up like the economist and call nine of the last five parallels.

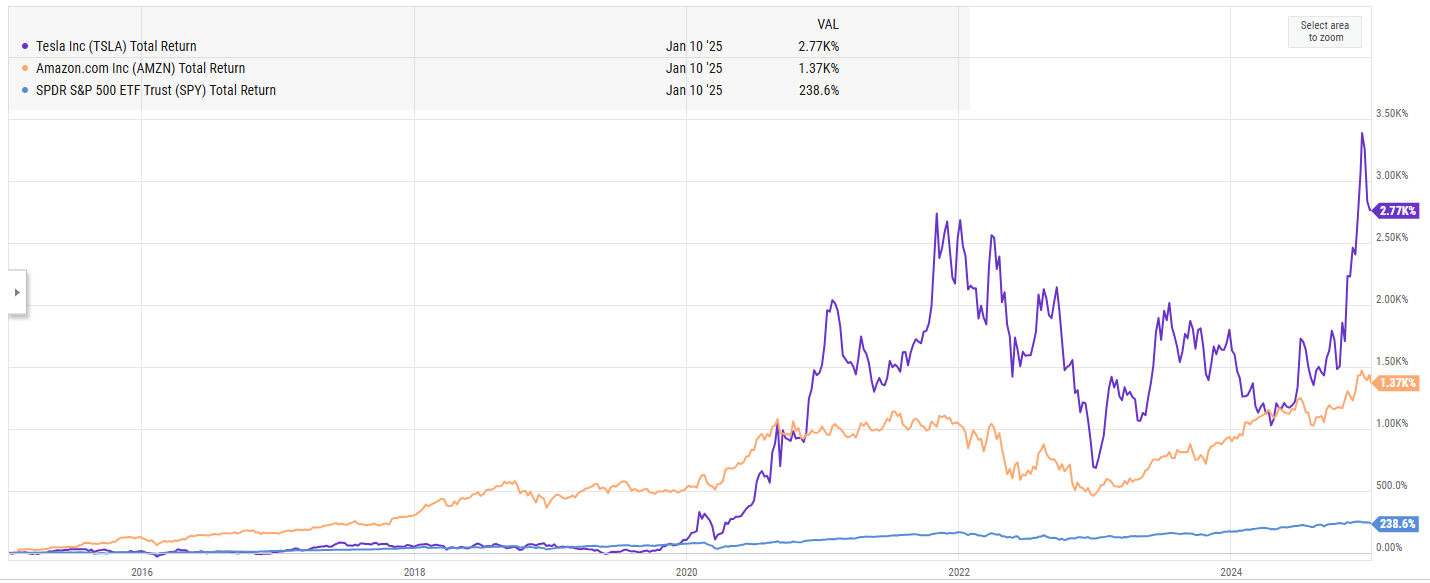

Let me give you an example that I think fits nicely. In the mid-2010s, David Einhorn somewhat famously had his “bubble basket” of shorts. The headliner of these shorts were Tesla and Amazon, but he had a few others in there (note: I generally like Einhorn, so I chose Einhorn not to pick on him specifically but because he’s a high profile example with CNBC articles detailing his Bubble Basket; there were plenty of other investors who had similar thesis but weren’t featured on CNBC so I can’t use them as an example!). The basic thesis behind the “bubble basket” is that while Tesla and Amazon might be great companies with great products, the economics of their businesses were terribly flawed as they reported very little (if any) profits, and history suggested the companies would fail to grow into their sky-high multiples…. and as the stocks continued to perform well through the 2010s, I remember more and more calls that compared the market then to the dotcom bubble.

Obviously, the bubble basket did not work out well in hindsight: Tesla, Amazon, and the like represented a new breed of company that have defied a lot of traditional expectations. That doesn’t mean things will work out for them in the future, but obviously if you were shorting them in 2015 you were pretty wrong given their subsequent business and stock price performance.

So here’s what I’m wondering: when I’m reading these older finance books and seeing parallels to today’s market, is that actually useful or is that just me trying to be intellectually sophisticated but costing myself money? Let me put it a different way: if I can read a history book and see parallels between a fraud situation in 1950 and a company I’m looking at today and avoid that company, that’s awesome and a great use of time…. but if I read the book and see a parallel between that situation and 20 different investments, avoid them all, and 1 was a fraud while the other 19 were grand slams, then I’ve probably cost myself money. Similarly, if I use a book and see a parallels between the current market and the dotcom bubble and avoid a big crash, great use of time / energy!!!!! But I know many people who have been using books and parallels to argue the market is in a bubble / overvalued since 2010, and that hasn’t exactly worked out well for them!

How can you strike that delicate balance of learning from history and using it to avoid repeating the mistakes of the past without overgeneralizing and missing out on opportunities in the present.

That’s my food for thought this weekend!

PS- I should mention I’ve been reading More Than a Numbers Game to prep for my first fintwit book club podcast with Byrne Hobart; I’m really excited for recording it this afternoon. If you have any questions you’d like us to address on the podcast, please feel free to lob them my way!

PPS- I used learning from prior market mistakes to avoid drawdowns as my core example here, but you can also imagine the reverse…. how many times have you heard someone proclaim a mini-conglomerate the next Berkshire Hathaway? I’ve probably heard of ten, and none of them came close to hitting that bar. So you could imagine how you don’t want to learn the “upside” lessons of the past and incorrectly apply them as well!

PPPS- I’d this paragraph in the book up against any other paragraph in any finance book “Financial professionals facilitating smooth earnings growth became rock stars in the business press. CFO magazine’s annual excellence awards cited WorldCom’s Scott Sullivan in 1998, Enron’s Andrew Fastow in 1999, and Tyco’s Mark Swartz in 2000. The federal government would indict all three”

This might be slightly apples to oranges; More than a numbers isn’t perfectly clear on this but seems to suggest that they’re comparing cumulative railroad spend to American GDP. Either way, I think we are far, far short of $11 trillion having been spent on AI!

The book actually notes this use of dividends to project better profits / company than the income statement would suggest in multiple sections; for example, another section includes “In the absence of income figures, investors turned to dividend payments as a crude signal of earning power. Unscrupulous managers could pay large early dividends out of contributed capital to give the impression of robust earnings.

it's not just willing to accept 1 fraud\failure out of 20 (which would be amazing), but it's having no idea whether you will have 1 or 10 failures.