There are a heck of a lot of companies out there with huge net cash positions on their balance sheet. This “company sitting on a huge cash position” can happen through a bunch of different corporate actions (the company can make a one time windfall, the company can sell off a big division, etc.) or even through a company just retaining all their earnings for several years in a row, but it generally happens through one of two paths:

The company went public when the market was hot (i.e. in 2021) at an insane valuation (either through an IPO or SPAC). They raised a whole boatload of money; the stock has likely been slaughtered since then, but the company has managed to sit on that huge cash balance sheet.

The company is a biotech / pharma company that had a promising drug. They raised a ton of money to pursue development….. but ultimately, the drug failed, and now the company is just a huge cash pile and investors are left wondering what to do with it.

There are honestly too many examples of both types of companies to go through here, but a nice example of the former would be WISH (current market cap ~$125m versus >$400m in cash + marketables thanks to the $1.1B they raised in an IPO) and a nice example of the later would be RAIN ($30m in market cap versus >$75m in cash after their key drug did not meet its primary endpoints). I do not have position in either security and am clearly not endorsing either (to be clear, I never endorse securities. Check out our disclaimer, which includes a paragraph in all caps just to let you know it’s very serious, here); I’m just pointing them out as easy and obvious examples of the types of securities / companies I’m thinking about here.

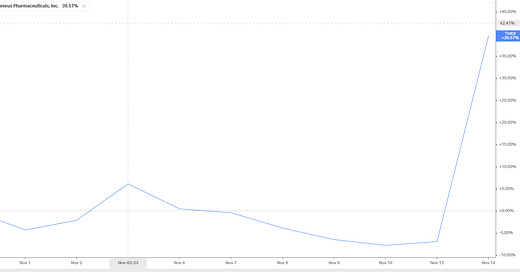

When a company looks like WISH or RAIN, it’s generally trading there because of corporate governance concerns. 95% of the time in those situations, shareholders would be best served by the company just returning all the cash to shareholders, but the company trades at a discount because management has entrenched themselves in some way and investors are discounting that the cash is more likely to get burnt on desperate turnarounds (and possibly lining management’s pockets) than it is to get returned to shareholders. If and when the company decides to return the cash to shareholders, their stock often has a big upward move like the one THRX had earlier this week (h/t Clark Street; disclosure I have a very small position) as investors reassess the corporate governance discount.

So those “huge discount to cash” cases are clear corporate governance issues. However, there’s another type of net cash business that I think is more interesting and that I think a lot of investor misunderstand / model wrong. And that’s the business that has a lot of its market cap in net cash, but also has a viable (or potentially viable) business attached to it.

A decent example of this would be something like BLDE. BLDE is not for me and I have done very little work on it, but I could see how you could talk yourself into it having a shot at being a huge business so that’s not to disparage it. However, I chose it because it’s a perfect example of the “has a lot of cash” example I wanted to use: the company has a market cap of $250m, and it has net cash on its balance sheet of $170m. So the net cash makes up a lot, but not all, of the company’s market cap / EV.

A lot of times when I talk to investors about a set up like BLDE, they’ll say something like “Plus the company is finally getting paid on their cash balance! With $170m in net cash, they’ll earn $8.5m/year in interest!” They’ll often say it with pride or like that’s some selling point for the investment. If you break down what they’re saying, a big part of it is “two years ago, that cash sat on their balance sheet and earned nothing, but now they’ll get a return on it, and because they’re getting interest on their cash the P/E multiple we’re paying is going way down!”

I get the excitement, but I think that it is 100% wrong. Having this much cash on a balance sheet is wildly inefficient, and it doesn’t get exciting as interest rates rise. In fact, it gets more inefficient as rates go up!

Let’s refocus on BLDE and pretend that their balance sheet has been static for the past few years. Two years ago, they had $170m in cash on their balance sheet, and it earned nothing. If you, as a shareholder, had that cash in your hands / sitting in your bank account, it would still earn nothing.

Compare that to today. BLDE’s $170m in cash gets $8.5m/year in interest…. but BLDE needs to pay taxes on that interest. With a ~21% tax rate, the company would actually be earning ~$6.7m in cash that they could dividend out to their shareholders every year. In contrast, if the investors have the full $170m already in their hands / bank accounts, they’d be getting $8.5m/year in interest without that corporate level tax (note: of course investors need to pay tax on what they earn, but they also pay taxes on dividends received. So yes, I did a little simplifying, but the point here is that having a company run a huge cash balance and just clip interest is actually hugely inefficient from a tax perspective as shareholders are paying double taxation on a risk free position!).

So, from a tax perspective, I think having those huge cash balances is just very suboptimal. However, there are two other ways that a large cash balance is inefficient and can distort, and I actually think they’re even worse for shareholders than that tax inefficiency.

The first is management bonuses. A lot of management teams have an EPS target (or net income target, or even an earnings before taxes target) in their annual bonus structure. Interest income from cash improves EPS / net income / EBT, so you can have a lot of execs that are getting boosted / hitting incentive targets simply because cash that used to earn 0% is now getting 5%+ and giving them a huge boost to hitting EPS targets.

The second relates to shareholder returns. Our goal as investors is to outperform the market on a long term basis, and it is really hard to outperform the market if the company you’re investing in carries too much cash. Let’s use BLDE again: they currently have a market cap of $250m with $170m in cash, so the market is implying the business is worth $80m. Let’s say you think the business is actually worth $160m, or a double. And let’s say you’re right, and the market comes to agree with you in three years. In BLDE’s current set up, in three years BLDE would be worth ~$350m ($160m for the core business, plus the $170m cash balance, plus I’m giving them a little extra for interest income on the cash and ignoring likely cash burn along the way). That’s a 40% gain over three years. Certainly better than a sharp stick in the eye, but that’s barely above market returns (if you assume the market does 8%/year, you’d get a 25% return just buying the market).

In contrast, let’s say BLDE was operating with no net cash today. Assuming the same valuation of the business, its current market cap would simply be $80m, and if you were right the market cap would be $160m in three years. That’s a three year double, or a >25% IRR. Posting 25%+ IRR is legendary; if you can do that, you’ll be among the best investors in history.

So that huge cash balance serves as a mammoth drag on returns. I’d much rather see a company I own pay out the majority of their excess cash and let me bet squarely on their business than see them hold a huge cash balance as a buffer for a rainy day. A lot of times, management will say they’re holding a big cash balance to help them through a downturn or so they can make some type of crazy good buy when the market turns (either an acquisition or buying back stock). That sounds great in theory, but, in general, the types of managers who actually will lean into a market panic to buy something or buy their own stock back when it’s cheap are quite rare, and most companies that run with a huge cash balance tend to just sit on their thumbs and do nothing when markets panic and end up blowing their cash on an average or below average acquisition when the market is rosy.

Anyway, this post has gotten long and rambling, so let me come back to the core thing I was trying to relay: now that ZIRP is (apparently) dead and companies are earning interest on their cash, you’ll see a lot of investors point to interest on cash balances as a source of upside. You need to reject that type of thinking. Huge cash balances are inefficient and serve as a drag on returns on a whole host of levels. You could do better with that cash in your bank account, earning a direct return for you (or giving you the optionality to buy more stock) than you could do with it sitting on the company’s balance sheet.

If you’re buying a company with a big net cash balance, you better be very sure that the business is wildly undervalued or that management has good plans for that cash; otherwise, it’s a real recipe for underperformance.

(Update: I got a lot of great feedback on this post, so I posted a follow up with some feedback / response here)

Great points here. On the larger cap front, Palantir comes to mind. The company is sitting on gold bars (absolutely ridiculous, and they’re being sued over it) and over $1 billion in cash that just earns a ton of interest. The stock’s fanboys eat it up because it drives net profitability, but it’s completely missing the point as to the sheer inefficiency of excess cash, per your points.

Exhibit A is probably US vs. Chinese mega-cap tech where US mega-cap tech ploughed excess cash into stock buybacks, in some cases borrowing to turbocharge buybacks, whereas Chinese mega-cap tech hoarded cash and continue to trade at very low enterprise valuations.

GLPG is standout among negative EV biotech in absolute dollar (or euro) terms: they have ~ $4.05B in cash or ~ $63/share vs. a historical annual cash burn of ~ $6.70/share dropping to ~ $3.70/share following the divestiture of their legacy business. The plan is to follow the well-proven playbook of biotech value creation: shovel the cash into the incinerator of business development; which if executed well, can generate life-changing returns.

The elevator pitch is that public investors are being offered the opportunity to invest in a biotech venture firm run by an industry (maybe minor) rock star who is grounded in science and likely has a world beating rolodex at what in retrospect may be a cyclical trough in biotech valuations.

But wait, there's more: manic LPs are offering to sell you their interests at a 40% discount to NAV!

Many investors, perhaps yourself included, will not find this pitch persuasive; nevertheless it is (mildly) interesting to observe that framing the opportunity in these terms maybe makes it more somewhat more appealing to professional investors, many of whom love buying at a discount, vs. "let me introduce you to Yet Another Negative EV Biotech".