This month has been “offshore month” on the blog. I did a long series on the (possible) inflection in the offshore space, as well as two podcasts (episode #146 (with Tidewater’s management) and episode #147 (with Judd Arnold).

It’s early, but so far those posts have proved very fortuitously timed. Last weekend the WSJ had an article “the offshore oil business is gushing again” which covered many of the points highlighted in my series. It’s always nice to beat a major publication to a story…. but it’s even nicer to get a set of articles out right before a major move in a sector, and the offshore space has been on absolute fire year to date / since those articles and pods started coming out.

Anyway, short term moves are mainly luck, and I’m sure the market gods will spite me for spiking the football so early / quickly.

But since that series, I’ve gotten a lot of suggestions on what the “next” offshore could be. I threw three out (telecom / media, Public REITs, and FANG) in a post earlier this month, but while all of them had interesting things going for them, none of them had quite the same supply / demand dynamics as offshore.

Readers have thrown out more interesting examples. Coal has gotten tossed around for obvious reasons. All varieties of shipping and tankers have popped up as well. Whole countries that have been starved of capital for years have been popular answers (at least five people responded with Argentina). And, while coal was the most popular answer, different types of commodities were popular answers as well, with several people pegging copper and uranium as particularly interesting given supply/demand dynamics and years of underinvestment.

All great answers…. but as I’ve thought about it over the past few weeks, there’s one sector that I think is most likely to have similar dynamics and I don’t believe a single listener mentioned them to me. Given how wild the profit and cash flow story is in the sector currently, I think that shows just how few investors are paying attention to the space (or perhaps I’m just biased and making up stories!).

The sector? Refining.

Long time readers (with good memories) will recall I’ve mentioned refining several times recently. I mentioned them briefly in “what Buffett sees in energy” and discussed their record margins and aggressive capital returns here.

But, to refresh, to me refiners have a powerful combination of three different things that set them up like the “offshore" trade:

Cheap to reasonably valued on midcycle margins

Absolutely gushing cash flow

Likely to realize above midcycle margins for a long, long time given ongoing supply/demand issues.

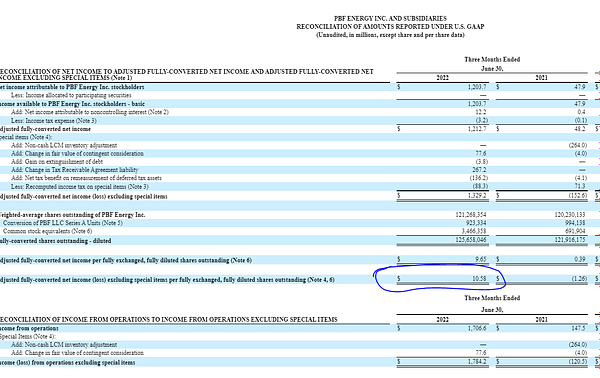

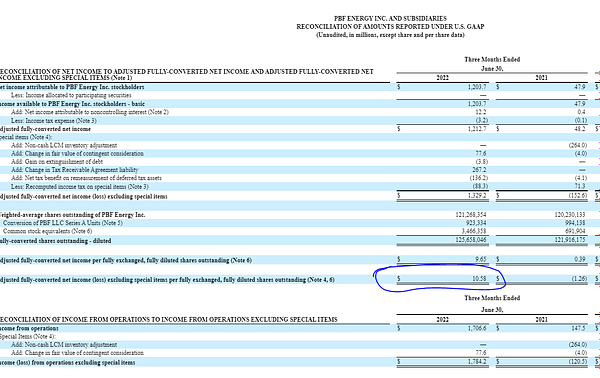

In fact, given they are already gushing free cash flow and cheap on midcycle numbers, you could argue refiners are further along on the “offshore” trade than offshore itself is (though offshore has more exposure to an absolute face ripper on day rates!). I’ll dive more into that “gushing cash flow” thing later, but I might as well start with perhaps my favorite stat of 2022. In July 2022, PBF was trading for ~$30/share. It reported $10/share in EPS for Q2’22 alone.

Normally when you see a company print ~a third of their market cap in earnings in one quarter, it happens because they had some massive gain on sale or one time item. That was not the case for PBF; margins just went so crazy that they literally just minted a third of their market cap. In fact, if anything a change in their tax receivable held net income down more than it otherwise would have.

And PBF was by far no means unique in the cash gush. Across the refining space you’re seeing companies just absolutely print money given how massive crack spreads are currently.

Anyway, I’m probably getting a little ahead of myself. Let’s walk through each of the three points of the thesis. I’ll try to be thorough / not use tons of jargon, but this is not an industry deep dive, so I’m not going to be able to cover everything. If you’re looking to learn more about refiners I think the place to start is Valero’s (VLO) investor site, as they’ve got a bunch of really informative presentations on the sector. (Editor’s note: I wrote this paragraph before writing the rest of this thesis…. and I lied. I went pretty deep into the industry, though refining is quite complex so it would have been easy to go deeper. I’m probably not known for being concise with my writing, and this post isn’t changing anyone’s mind. My bad!).

Let’s start with the first part of the thesis: refiners are cheap/reasonably valued on midcycle margins.

Point #1: Refiners are cheap / reasonably valued on midcycle margins

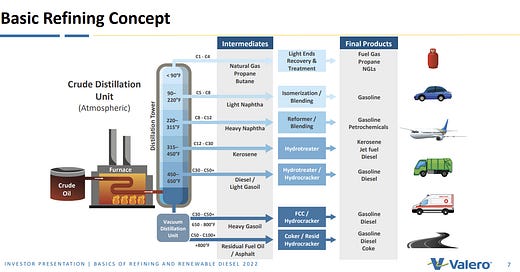

Running a refiner is wildly complex, but it’s actually pretty simple to explain at a high level. Refiners take a barrel of crude oil and “crack” it to turn it into a bunch of different product (jet fuel, gasoline, diesel, etc.).

Refiners run on a “crack spread”: the margin between what they pay for the barrel of oil and what they sell the different parts for. For example, if they paid $70 for a barrel of oil and turned it into a bunch of gasoline and diesel that they sold for $80 in total, their crack margin would be $10/barrel ($80 in revenue less $70 cost = $10).

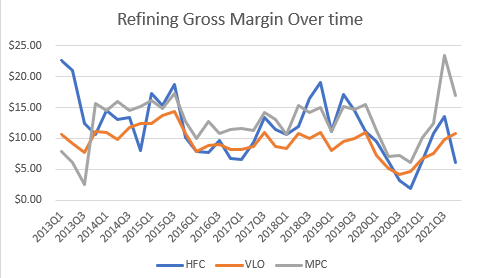

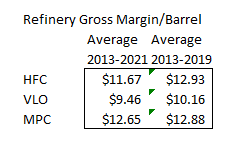

Like any cyclical industry, crack spreads can be volatile. Crack spreads approached zero when basically all travel and commuting shut down in 2020 thanks to COVID. My friends at Daloopa have three of the refiners modeled (MPC, VLO, and HFC); I took the models and threw those three companies quarterly crack spreads into a chart below. These are some truly wild swings; MPC goes from $2.55/barrel in margin in Q3’13 to $14.55/barrel just one year later. There aren’t many industries where your unit gross margin can >6x inside of a year!

In industries where margins can vary widely from year to year, the way you generally want to look at valuation is by finding “mid-cycle” margins (i.e. what the company will earn when the industry isn’t crazy hot or cold, or just the average annual earnings over a full cycle) and slapping a multiple on that number.

Each refiner has a bunch of different complexities (the complexities of the refinery, if they can source oil cheaper than market prices, etc), so there’s no one number than fits all companies…. but you’re probably safe to use a low double digit crack for most refining companies. For example, if you just use the Daloopa data from the chart for the three companies above, you’d see they average $10-$12/barrel in margin from 2013-2021. If you stripped out 2020 and 2021 (those were pretty unique years), the margins would be a bit higher.

So that’s generally how you want to think about valuing a refinery: figure out their mid-cycle earnings and slap a multiple on it.

The companies seem to agree with this valuation; HF Sinclair (which now trades under the awesome ticker DINO) puts the slide below in their investor decks.

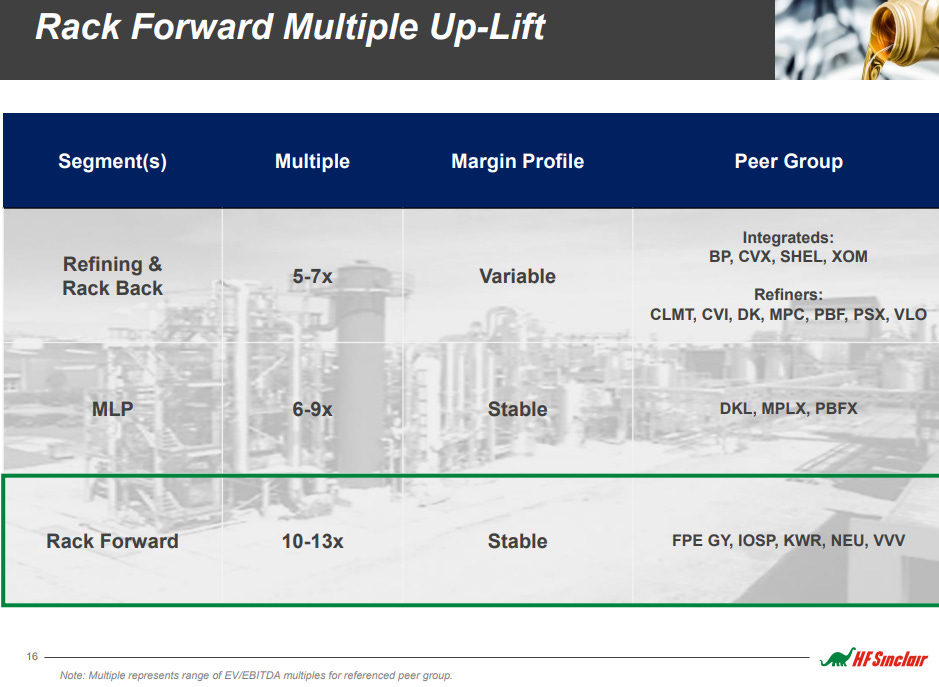

Once you find the refiners midcycle earnings, you’d then want to slap a multiple on them. Given the cyclicality, asset intensity, and terminal value questions for refineries, a mid-single digit multiple is probably appropriate. DINO agrees; they suggest using a 5-7x multiple on their refining business:

Now here’s where things get a little tricky: most of the refiners have assets outside of their refineries. For example, MPC consolidates their MLP, MPLX. That can make it slightly difficult to value because you have to back MPLX out of the income statement and the balance sheet and then add the value of MPC’s MPLX shares. Other peers are even more complex. CVI owns a controlling stake in a fertilizer company (UAN). DINO, as shown above, has an MLP and some chemical businesses. VLO has a ton of renewable assets (almost all the refiners have renewable plays, but VLO is far and away the leader and theirs have a lot of value!).

I’m not going to break down the value of every refining company… but, in general, I find they all trade for ~6-8x “average” EBITDA using this method. For example, let’s look at CVI (which I picked because they are undergoing a spinoff event and because Carl Icahn controls them and recently called them his favorite idea, so they should have some sex appeal!). CVI averaged $561m in EBITDA/year from 2011-2021. If you back out their ownership in UAN and adjust their balance sheet for the UAN debt and the dividend CVI paid in Q4, they’ve got an EV of ~$4.1B (note: that gives them no credit for the cash generated in Q4, and as I’ll discuss in point #2 they almost certainly generated a ton of cash in Q4!). That would put CVI trading at ~7.3x average EBITDA…. and the number would look even cheaper if you excluded 2020 and 2021 from the averages on the theory that those were pretty crazy years!.

If you break out all the different parts for refineries, most are trading for a similar multiple. Some might be a little cheaper, some might be a little more expensive, and you might want to tweak some of their earnings up or down from these average levels based on things that have happened to their individual assets…. but in general all are trading in the ~7-8x “average EBITDA” range.

Refiners are absolutely massive, very asset intensive businesses, so I could see the value police coming for me and saying “How dare you use EBITDA to value these? What about actual cash flow?”

Calm down there officer! This section is already running wildly long, so I’m not going to go crazy defending myself in value court. I’ll just note that refiners generate plenty of cash flow over a cycle. Below I’ve got CVI’s petrol only EBITDA, MCX, and total capex from 2013-2021.

No cash flow problem there! EBITDA is converting reasonably well to unlevered free cash flow; I don’t think it’s a stretch to say a ~7-8x EBITDA multiple would get you to a <10x unlevered free cash flow multiple on these businesses. You’ll then need to start factoring in things like taxes and interest expenses (though these companies have printed so much money recently that most of them can’t figure out how to run with any leverage), but bottom line is we’re not talking crazy multiples or anything.

Hopefully I’ve established point #1: refiners are reasonably cheap to fairly valued on mid-cycle margins at current prices. Let’s now turn to point #2: refiners are absolutely gushing cash flow currently.

Point #2: Refiners are gushing cash

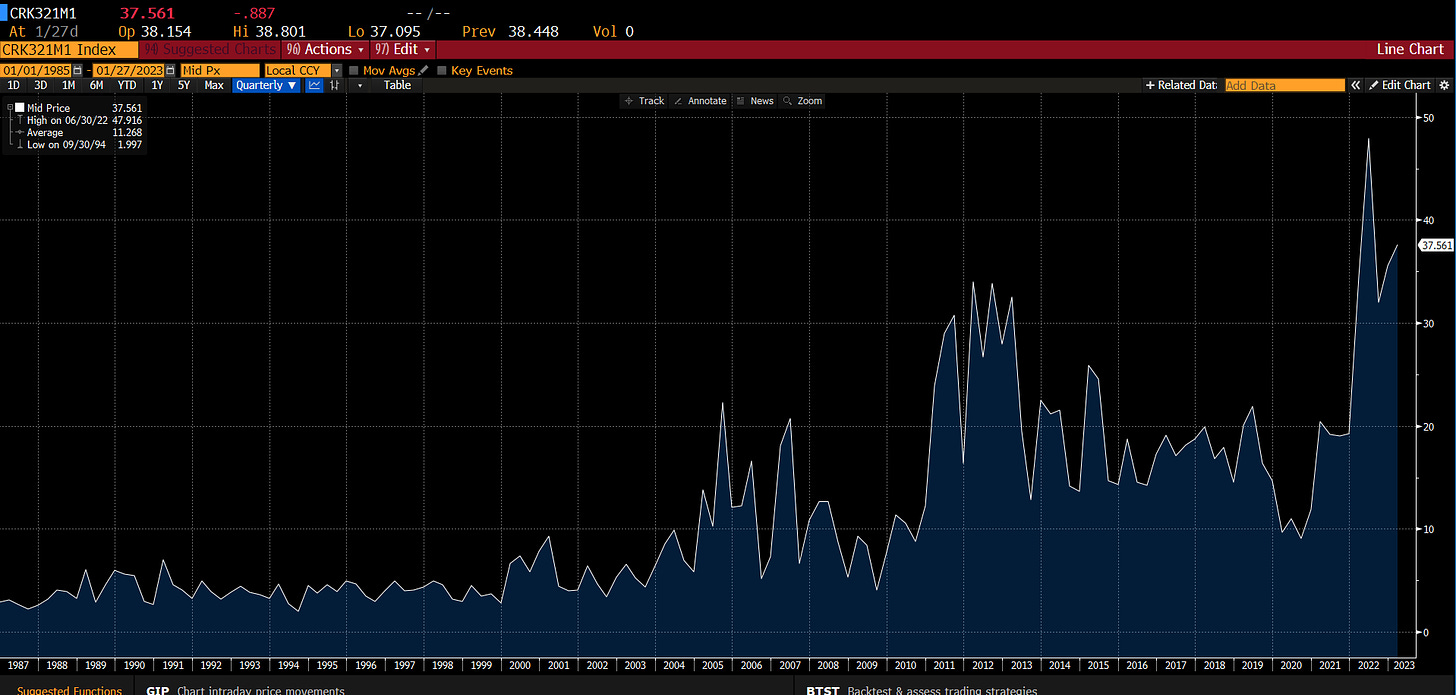

I mentioned above that refiners run on crack spreads. Over the past year, we’ve seen record crack spread levels. And I mean that literally: we’ve never seen crack spreads as high as we’re seeing today. Bloomberg has NYMEX crack spreads going back to 1987, since early 2022 crack spreads have consistently been well above their previous record highs from the early 2010s.

Those record cracks are driving insane amounts of cash flow to the refining companies. I’ve already mentioned my favorite example in earlier in the post, but it’s so wild I’ll mention it here again: PBF earned a third of its market cap in one quarter.

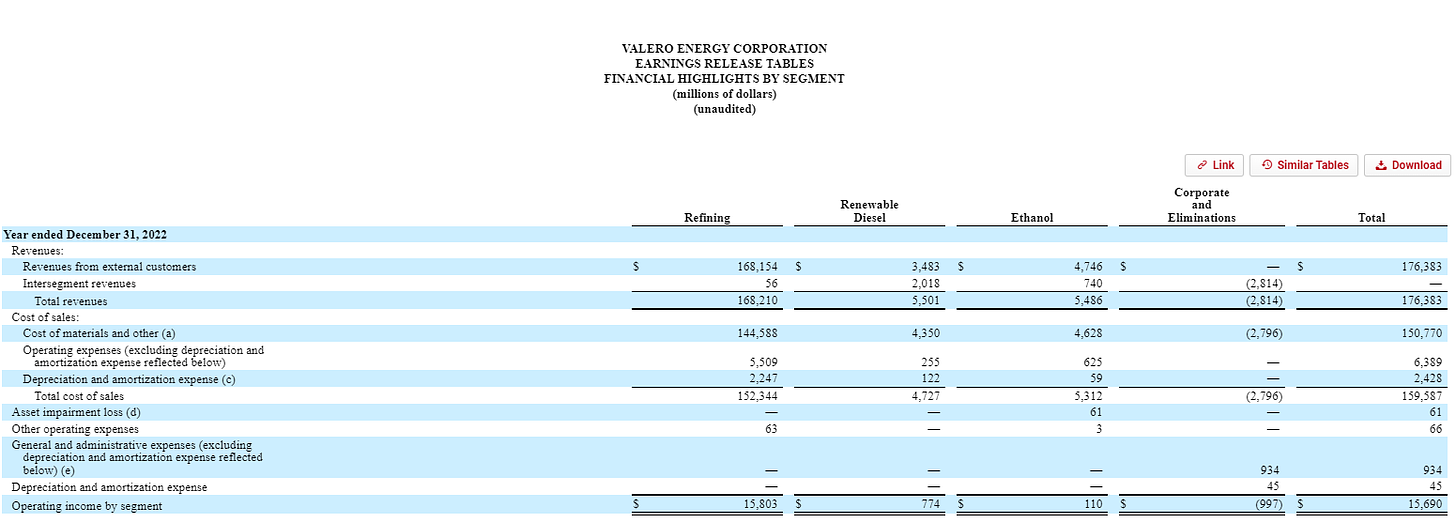

As you might expect given continued elevated cracks, those results have roughly continued for all refiners. Take VLO: it’s a ~$60B corporation with a massively, massively valuable renewable JV. They reported earnings last week. Their refining segment did >$4B in EBIT…. in the fourth quarter alone.

Again, VLO is a ~$60B corporation. At current earnings, you’re buying all of VLO for ~12x their quarterly refining earnings and getting everything else (including their renewable JV, which is just ramping, earned ~$775m in 2022, and is probably worth a low double digit multiple) for free.

And yes, these are record crack spreads. But they sustained for all of 2022! VLO earned just shy of $16B in refining operating income in 2022.

I showed in part #1 how refiners are reasonably priced on mid-cycle margins. No one is underwriting refiners at these margin levels or anything close to them. But the fact remains crack spreads were insanely elevated in 2022, they remain insanely elevated as I write this, and the futures curves for cracks are probably not the most reliable but they show continued strong crack spreads.

So yes, crack spreads probably won’t stay this elevated…. but as long as they remain around here you’re going to see refiners print 3-5% of their market caps in cash flow every month.

And the refiners are very clear about what they’re going to do with that cash flow: return it to shareholders. Here’s a quote from CVI’s Q3’22 earnings call that sums it up nicely:

We're a cash machine, and… if we earn it, we're going to pay it out to shareholders. And I think we've shown that in the last 2 quarters that, that is truly what we march to.

Basically every refiner is following some variation of CVI’s marching orders. Some refiners return the cash through dividends, some through buybacks, and most through a combination of the two. But the refiners are gushing cash flow right now, that seems set to continue, and they will be returning all of it to shareholders in one form or another (it’s worth noting that in 2022 they were doing a combination of returning cash to shareholders and paying down debt, but they all made so much money that they’re all basically way under levered, and many are running with no net debt at this point).

Alright, that’s it for point #2: refiners are currently gushing cash flow. When you combine it with point #1 (refiners are cheap on midcycle margins), I think you get a really interesting set up: you could look at an investment in a refinery as buying into a business at a reasonable mid-cycle valuation and getting the current super-normal gush of cash flow for free. Every day that margins remain elevated is free upside to the thesis / the value you paid.

But I think where the thesis really kicks into overdrive is with point #3: refining margins are likely to remain above midcycle margins for a long, long time. In fact, I’m not sure if the “old” midcycle margins are relevant anymore; given structural changes in the refining market, I think you could argue refining midcycle margins have shifted permanently higher.

This post is running long…. so I’ll be back later this week to dive into point #3 as well as discussing some risks and downsides to the thesis. How’s that for a cliff hanger?

See you later this week.

Thanks for the article, as always. We agree with your calculation that this sector has room to move.

Yesterday we posted about Icahn, and briefly mentioned CVI and it’s potential spin-off of UAN. It’s an intriguing setup.

https://specialsituationinvesting.substack.com/p/six-reasons-to-consider-riding-carl

One point to add is that it is very difficult to build a refinery in America, so adding capacity to address high crack spreads is not going to happen. Given the capacity constraints, there is a risk of supply shocks which add to the risk premium.