Welcome to the second part of my “refiners parallels to the offshore inflection thesis. Last weekend, I posted part 1 of the thesis, which covered why I’m interested in refiners, how they’re fairly valued on mid-cycle earnings, and how much cash flow they’re currently gushing.

Today I’m going to write about the most interesting part of the refiner thesis: why I think margins are likely to be structurally higher going forward.

Of course, saying something is different or has structurally changed in a commodity industry is “famous last words” type stuff. Commodities are…. well, commodities, for a reason: one unit is the same as the next, and high prices are a clear sign to the market to figure out how the bring more supply online. Eventually, human ingenuity and economics win out, and high margins/prices will prove their own downfall.

That’s why part #1 of this thesis is so important. Even if I’m wrong that margins are structurally higher for longer, you’re not paying much (if any) premium for refiners at current levels, and they are gushing cash flow today in a way that the market seems to be giving them little credit for.

But I think it’s highly likely that domestic refining margins will be higher for longer for a two major reasonsreasons:

Domestic natural gas prices provide U.S. refiners a sustained competitive advantage

Refining capacity has come down significantly post pandemic, as older refineries have shut down and several refineries have converted to renewable diesel. The capacity / supply lost from those refineries is never coming back, crating a tighter supply / demand dynamic (and higher margins!) going forward.

Let’s start with point #1: domestic natural gas prices provide U.S. refiners a competitive advantage.

Natural gas is a key piece of the refining process (refining requires lots of energy and heat; it’s so important that the price of natural gas and electricity is one of the top risk factors in Valero’s 10-K). Domestic natural gas has been cheaper than Europe’s for years; however, that differential has blown out over the past year thanks to Russia / Ukraine.

Valero has a nice slide illustrating this; in 2019, the domestic natural gas advantage gave a refiner ~$1/barrel cost advantage. In 3Q’22, the differential was worth ~$10/barrel.

It’s hard to see natural gas differentials for U.S. versus Europe going back to 2019 levels any time soon. If that differential remains, then using mid-cycle margins from the ~2010s is too pessimistic; U.S. refiners have a structural cost advantage, and that cost advantage should result in higher margins.

Note that this is not a small number; you might recall the chart below from part #1 ( it uses Daloopa data to grab the average grass refining margin/barrel for three refiners). It showed (and I estimated) normalized margins were in the low double digits/barrel.

If Valero’s numbers are right, then natural gas differential alone would be worth ~$10/barrel of margins in the current environment, or almost the entire mid-cycle margin I was discussing in part one. To put it bluntly, that’s an enormous number.

Note that if you wanted, you could probably go deeper on the natural gas angle and just turn it into a “U.S. has more energy stability than the rest of the world” thesis. The key input for a refinery is obviously oil; as I write this WTI is trading for ~$74/barrel while brent is ~$80. It’s not a perfect comparison / this is a simplification, but you could basically look at the Brent vs. WTI spread as another structural advantage for U.S. refining (if you believe WTI remains cheaper than Brent). However, I’d note that this edge doesn’t really translate to higher margins versus last cycle; WTI has traded for a discount to Brent pretty consistently over the past decade.

So that’s part one of the “higher margins for domestic refiners” thesis: energy security / lower natural gas prices.

Let’s turn to part #2: a reduction in capacity has shifted the supply demand curve.

The EIA has the U.S.’s refining capacity going back to the mid 80s. In 2021, refining capacity dipped to ~18.1m barrels/day, taking us back to ~2015’s refining level.

The reduction in capacity has been driven by a few things; namely, older refineries shutting down during the pandemic and some refineries getting converted to greener initiatives like renewable diesel. An example will show this best: in 2022, PSX made the final decision to convert their Rodeo facility into a renewable facility. The renewable facility will produce over 50k barrels/day of renewable fuels; even if we assume those are 1:1 with “normal” fuel barrels, that decision is still a massive reduction as the Rodeo facility previously had capacity of ~120k barrel/day (per PSX’s 10-K). And it would not surprise me to see continued capacity reductions in the near future; I know of a few other refineries that are taking off capacity currently to invest into renewables, and Lyondell is planning to shut their Houston refinery (representing ~264k barrel/day of capacity) down at the end of the year (a move they reconfirmed as recently as their earnings call this week!).

Anyway, the refining capacity reduction has also been very well covered; when gas prices were spiking last summer, Bloomberg, Forbes, NPR, WaPo, and S&P Global all had articles on what had happened to capacity. But just because it has been well covered does not make it less true or actionable!

Bottom line: we’ve seen a reduction in capacity over the past few years, and I would not be surprised if we saw a little more capacity taken offline over the next few years despite the great economics of refining at current cracks.

Normal economics suggests that when margins are high, you’ll see a massive supply response. Yes, it’ll likely take a few years to come online (you can’t build a refiner overnight), but you’d expect record cracks to result in some new supply coming online eventually.

That’s almost certainly not the case for refining for a few reasons. First, given regulatory headaches and NIMBY, I’m not sure if you could get a new refiner approved today. But, even ignoring that, a new refinery just wouldn’t make economic sense. Building a refinery would take years and billions of dollars (this Bloomberg article suggested it would take 10 years and $10 billion to build a new refinery; that seems directionally correct); it would require decades to get payback on that asset. Given the terminal value question of fossil fuels, no one is going to make that investment in the U.S. The last major refinery opened in the U.S. in 1977 and we’ll almost certainly never get another new one.

With no new refineries likely every to come on, the only way to increase capacity is to expand capacity at existing refineries or to run existing refineries with less downtime. These can help, but I think we’re close to the limit for both. The announced refinery expansions barely add up to one new refineries worth of capacity, and refineries were running close to capacity for most of the back half of 2022 (you can see monthly refinery capacity utilization here) and we’re looking at a heavy maintaince / turnaround season in early 2023 to make up for some of that heavy usage.

Without U.S. capacity left to come online, any shortages would be need to made up by the global markets. But that would be expensive; the rest of the world seems similarly short refining capacity, and while there are new refiners coming on in Asia, those will likely be needed to meet growing demand there and meet any reduction in Russian refined products. Plus, given the nat gas and Brent / WTI differentials discussed earlier plus the cost of shipping, if we got to the point where the U.S. is importing a lot of supply globally it’s almost certainly because margins are way, way higher than normal!

So throw it all together and I think you’ve got a perfect storm for the refining sector: they’re trading at reasonable multiples on mid-cycle margins, they’re gushing cash flow right now, and margins are likely to be materially higher than mid-cycle for a long, long time. Plus, management seems to have gotten the memo on capital allocation, as basically every refiner is taking their gush of cash flow and aggressively returning it to shareholders (last year they were also paying down debt, but they made so much money that all of them have pretty much paid down all of their debt so their only remaining option is to give it back to shareholders!). In a way, this reminds me of the offshore trade except better: in offshore, every management team has promised that they’ll be disciplined / rational with any cash gush and return it to shareholders. Refiners are promising something similar…. except they’re already delivering on those promises and they don’t really have the option to newbuild even if they wanted one!

A few weeks ago, the WSJ ran an article on California’s mysteriously high gas prices. That article was more focused on retail gas stations, not refiners, but it had one line that really jumped out to me:

A rapid shift can be a bonanza for gas stations and refiners that stick around. As Mr. Kloza puts it, “it’s a sunset industry, but it’s going to be a beautiful sunset.””

Refining is, eventually, a sunsetting industry. But the sunset is a long time away, and it looks like it’s going to be a very long, very beautiful sunset for refiners and their shareholders.

Odds and ends

Just speaking of sunsetting, my guess is that refiners will be around for a long time but that doesn’t mean you don’t eventually have demand responses here. As electric cars continue to penetrate the car stock, you’re going to see them sap away the demand for gasoline. And even if electric cars come along slower than expected, continued rising gas prices could cause manufacturers to push out more fuel efficient cars (MPG went from the low teens in the 70s to the low 20s today; a few years of $5/gallon gas and I’d guess we could see average MPG heading over 30!). Regulatory subsidies for renewable diesel and sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) could impact demand as well. I tend to think, even with a lot of subsidies, the real demand impact from these programs are ~10 years out, and by then all of the refiners will likely have made double their market caps in cash flow…. but if you’re looking to really poke a hole in the refiners thesis, I think it’s in a “demand evaporates faster than anyone thinks” way more so than a “we get a lot of unexpected supply”.

I mentioned it briefly in the article, but the next round of sanctions includes Russian refined stuff. That probably matters more for Europe than domestic cracks, and I’d guess the market’s efficient enough to have factored it into “the curve,” but who knows. Here’s how MPC talked about it on their Q4 earnings call:

“So leading into the sanctions, as you'd expect, we saw meaningful deinventorying coming out of Russia, getting out of the sanctions, coupled with a reinventory large parts of Northwest Europe. So as a result, we're entering the sanction period of time at really historically high levels of inventory, particularly in Europe. So we view it as a 2Q and beyond time line perspective. But directionally, we see it as bullish for cracks. We see [800] to 1 million barrels a day of, I'll call them structural historical imports into Northwest Europe coming out of Russia.”

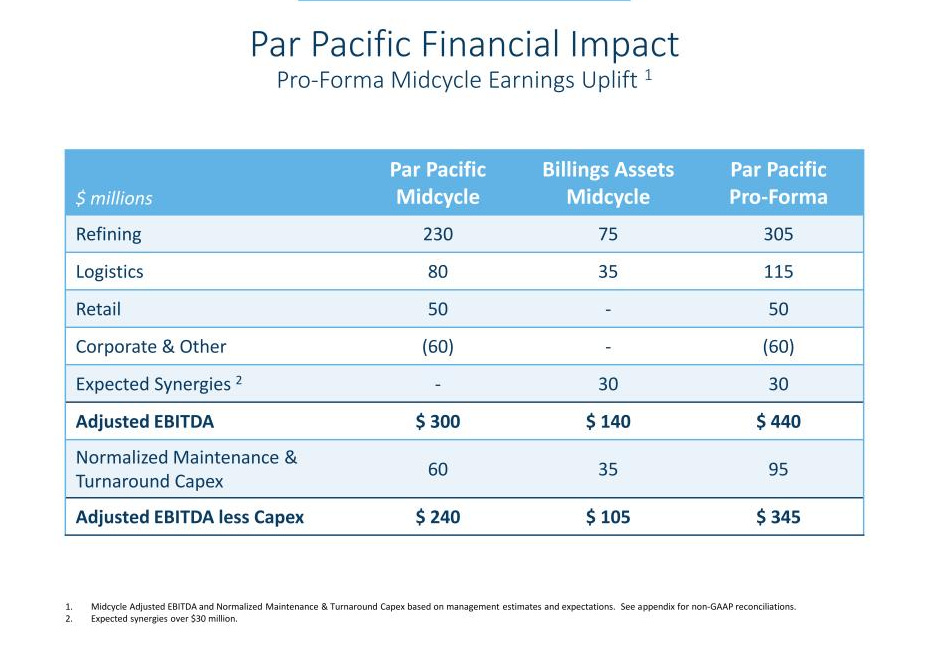

One interesting thing about the refiners: we have seen a few refinery deals recently where majors sold smaller, noncore assets to smaller players. The two I’m thinking about are Shell selling their Mobile assets to Vertex in 2021 and Exxon selling their Billings assets to Par late last year. My guess is the buyer got great deals in both of those transactions as they were both priced at very low multiples (Exxon/Par/Billing was <3x midcycle FCF; Vertex was probably <1x NTM FCF when it closed), and the sellers were happy to let them go given the headache of owning / operating non-core older / smaller refineries.

Vertex in particular seems to have gotten a great deal; they spent $75m to buy Mobile and the facility produced almost that much in EBITDA in the first six months after closing in April 2022 (though Vertex bundled all of those windfall profits away on a truly disastrous hedging program).

One could fairly ask: Exxon and Shell are two extremely sophisticated sellers. Are they handing the sellers a bag of goods when they’re selling these assets at multiples this low? I think the answer to that question is no. The facility Vertex bought is very outdated; Shell probably thought it was better to sell it and let someone else worry about what to do / how to close it than keep it on their books, and Vertex simply got lucky with a once in a generation crack spread blow out. For Exxon, I think Billings was a small noncore asset. Par probably got a good deal on it, but a lot of the low multiple comes from a big synergy number (see slide below); exclude that number, and Exxon got a much more reasonable price for a noncore asset.

I had the fortune / misfortune (depending on the year) of covering this space for awhile. Generally agree with your framing, but a few questions to think about:

1) There’s a bit of a disconnect between “cracks are structurally higher for longer” and “it doesn’t make sense to increase supply”. No one is ever building a new refinery in the US, but what are the incremental returns to a PADD 3 refiner adding an incremental distillation unit if you’re right about cracks? And while the ESG / NIMBY may be a headwind to new supply in the US, it sure won’t slow down overseas capacity growth.

2)The other question I have is whether the COVID-related mothballing has pulled forward earnings. When demand starts to flatten / decline later this decade, it’s going to take a much stronger price response to take out incremental refining capacity because a bunch of the high-cost, marginal capacity has already been taken off the cost curve.

Hey all:

I've also been looking at this space. I agree with a lot of the conclusions presented.

The cheapest refiner that I've come across is Blue Dolphin Energy (BDCO).

They are the smallest publicly traded refiner that I am aware of. They have gone up in price a bit, and now have a market cap of almost $30MM.

The most interesting thing is that they are probably trading for a P/E of LESS than 1.

They have had a tremendous problem with their debt load, but they made an agreement with their largest creditor. They are also earning money at an incredible rate, and has made progress on their debt in 2022. At the current rate of earnings, they will be able to pay off most of their debt this year. While their debt has gotten them into trouble in the past, they might be able to pay it off and not have to worry about it moving forward.

They also primarily refine jet fuel, which appears to have increasing demand. They have so much operating leverage, that if they can increase their net margin from 6% to 8%, that will boost earnings tremendously.

Earnings will also increase substantially as they pay off their high interest debt.

I don't think this is a high quality company, but with their improved balance sheet, I would think that this should trade for a P/E higher than 1. Heck, they might even be able to trade for a 4-5 P/E?

Anybody else been looking at this?