A lot of conversations in investing are asymmetric. My podcast is a great example (and also a great podcast; you should subscribe!); to have an informed conversation, I generally try to do ~a half-day’s worth of work on the company we’re discussing before a guest comes on, but I’m often talking to guests who have significant positions in the stock and have been following it closely for months or even years. It’s inevitable the guest is going to know way more than me on the company, and most of the knowledge is going to be flowing one way (from them to me and hopefully the listener!). But the same principle applies to an investor who is talking to a management team or an industry expert; the investor has (hopefully) done some work in the area, but they’re talking to someone who has spent their whole life inside a sector and lives/breathes it.

That asymmetry often means that there is an uneven exchange of knowledge where most of the knowledge is flowing from one side of the table to another. Asymmetry doesn’t mean a conversation can’t be fruitful; sometimes an investor can bring different knowledge that’s helpful to the conversation (for example, many management teams, particularly at smaller companies, are quite unsophisticated on capital allocation, so a discussion with an investor can provide the management team with some knowledge there), or an investor looking at a new-ish company/industry with fresh eyes can ask questions that someone who has been following a company for years might gloss over or might not have considered in a certain way. For example, every now and then, I’ll be talking to someone who is trying to use me to ramp up on a name, and they’ll ask a question that makes me realize my thesis is much stronger than I had originally thought, or they’ll frame a risk in a new light that makes me realize the position has more risk than I realized I was underwriting. Actually, that’s one of my goals for the podcasts: I hope guests come on and get wide publicity and fame for ideas that do spectacularly, but I also hope I can give a credible conversation that helps guests underwriting ideas (or that the publicity gets the idea into other people’s ears who can do a better job of pushing back / underwriting when I miss the ball!).

Anyway, I mention this because every now and then I’ll be talking to someone about a name and we’ll just be rolling. I’ll be impressed by the answer to every question I ask; not only can the guest credibly answer the questions I ask, but they’ll be able to provide answers to questions I didn’t know I even had. They’ll address risks I didn’t know where there and upsides that I hadn’t even dreamed of. I’ll be all bulled up on the name and the investor, and then I’ll ask another question and they’ll respond “The sky is green, the sun revolves around the earth, and a secret cabal of lizard people runs the company’s biggest competitor and they will go into hibernation once winter starts, allowing our company to take huge share.”

Ok, that’s a bit of a joke, but the analyst will respond with something that I know is so wrong that it’s about equivalent to that answer. And then that will make me wonder: how much credence can I give the thirty minutes of rational conversation before when the analyst is so clearly living in their own world on this answer?

Again, this can happen with management teams and companies too, so let me use a very public example to highlight exactly what I’m talking about.

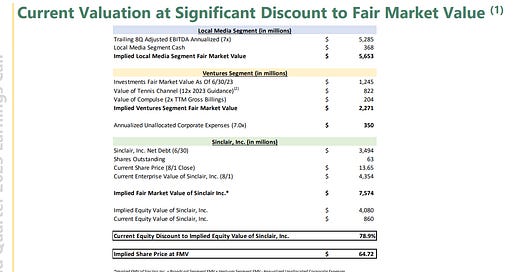

Long time readers will know that I am no fan of Sinclair (SBGI); I’ve considered them uninvestable since reading the Tribune / Sinclair lawsuit a few years ago. So you can take all of this with a grain of salt knowing it’s coming from someone with some negative bias…. but Sinclair has recently popped on my radar a few times. They recently published a deck that included a SOTP slide (included below), and with the stock trading at ~$14/share several investors have emailed me and said “damn, is there a wild amount of opportunity here?”

Anything can be an opportunity, and there’s no doubt Sinclair looks cheap… but the valuation of Tennis channel on that slide is the functional equivalent of claiming “the sky is green,” and, once you see that, I think it makes you question everything else on the slide as well as management’s competence / trustworthiness.

Why is that valuation so silly? Sinclair bought the Tennis Channel for $350m in 2016. Until this year, the Tennis channel was buried in Sinclair’s “other” segment (see, for example, the 2022 10-K), and the Tennis channel was honestly an afterthought. Sinclair barely mentioned it on their earnings calls and analyst days (their FY21 earnings call barely mentioned tennis!), and analysts didn’t really ask about it. In fact, in Sinclair’s Q1’23 earnings call, they admitted “we haven't talked Tennis in a few years.”

Sure, Sinclair had other stuff going on…. but their market cap was <$2B at the end of 2021 (with an EV of $5-6B; they had a lot of RSN debt consolidated that was non-recourse, so I’m just eyeballing it to sort it out); you’d have me believe Sinclair has turned a $350m investment into an almost $1B asset in Tennis that no one was talking or thinking about as recently as a few months ago?

Get out of here.

The financials (and logic) would back me up. Sinclair’s done a nice job of increasing Tennis channel’s distribution recently, but the Tennis channel is ultimately a linear TV business trying to pivot to a post-cable bundle / D2C world. This year is the first year SBGI’s disclosed the Tennis Channel’s financials (again, they were buried in the “other” segment until this year), and while Tennis is doing better than I’d guess something like ESPN is doing, revenue has stalled so far this year while expenses are going up as new rights deals kick in.

Those financials don’t exactly scream “double digit earnings multiple.” Nor do where peers trade; pull up the stock chart of any linear cable business and ask yourself if it’s likely Sinclair has somehow >2x’d Tennis Channel’s value over the past ~7 years.

So I’m extremely skeptical Tennis Channel is worth what they’re marking it at. Heck, I’m skeptical Tennis Channel is worth half what they’re marking it at (AMCX trades for ~6x forward EBITDA; it’s certainly more structurally challenged, but I’d also guess it’s significantly more strategic).

And, once you start questioning how ridiculous the Tennis channel valuation is, it raises plenty of other unflattering questions.

First, it makes you question the assumptions behind everything else on that SOTP slide.

But, perhaps more importantly, it raises serious questions about Sinclair’s go forward strategy. When you question the Tennis multiple for being completely ridiculous, it makes you question management’s trustworthiness or competence (or perhaps both). Either management is flat lying to shareholders about Tennis’s value in order to generate interest in the stock, or management believes the insane valuation they’ve placed on Tennis and they’re going to make decisions going forward based on that valuation.

I’ve seen it happen before where a management team is convinced their business is worth $100 while trades it for $25. The management team goes hog wild buying back shares at $25 and then $40 and $60 and ultimately as high as $80…. and then eventually the market is proven right that the business is worth $25, except management has destroyed so much value buying back stock at self-inflated prices that there’s almost no value left for shareholders. This “repurchase high, sell low” has happened to a lot of companies, particularly retailers, lately. Bed Bath & Beyond is my favorite example. They bought just shy of $12B of their stock since 2004, including almost $600m in they year before they filed for bankruptcy and, in one of the worst trades of all time, ~$46m in the year they filed for bankruptcy (at ~$17.50/share) before furiously issuing stock at the end of the year in a desperate attempt to stave off bankruptcy (they raised ~$115m at ~$5/share at the end of the fiscal year, and they continued to issue all the way down to buy a few more weeks before filing).

Something similar (though perhaps not as drastic) could easily happen at Sinclair: management could think Tennis is worth ~$1b, the market could think Tennis is worth $300m, and management could just buy a ton of stock at an implied valuation of $300m and then $500m and then $700m…. and ultimately destroy a ton of value when they’re proven wrong.

Perhaps this doesn’t matter. Sinclair is so cheap currently that maybe one silly assumption on the Tennis channel doesn’t matter, and you combine that cheapness with aggressive capital allocation (they bought back a ton of shares earlier this year, they have a ~7% dividend yield at current prices, and in Q2 they bought back $32m face value of debt at 65% of par, though currently they appear to have paused share buybacks in favor of debt buybacks) and you can easily argue shareholders have a big margin of safety even if Tennis channel is worth a quarter of what management thinks it is.

But management has a questionable history of corporate governance and capital allocation (the RSN deal (which, to be fair, both me and the market initially liked!), the tribune debacle I mentioned earlier, etc.) and they’re quite entrenched by their super voting shares (they control 81% of the vote). An entrenched management team with a history of questionable capital allocation that is currently clearly deluding themselves on value is absolutely worth a big discount; to me, the only question is if the current discount is too big or big enough?

This post got very Sinclair heavy, so let’s bring it back the the generality I started with: if an investor or management team makes a ton of great points and then suddenly says, “our business is worth more than apple, microsoft, and google combined?” what do you do? How do you assess everything else they’ve told you / you’ve talked about during the conversation?

When a management team does makes far out there statements, it’s a much bigger red flag to me. Management team decisions and world view has a direct impact on me as a shareholder; if they’re viewing something incorrectly, I need to assign a huge capital allocation / management discount to that company because that’s not easy to fix. If it’s from another investor, I can be more forgiving, but I need to spend a lot of time re-underwriting everything we’ve discussed going forward.

But, ultimately, my answer to this question, as it is with so many of the questions I pose on this blog, is “I don’t know.” And, heck, maybe I’m wrong and the sky is green!

PS- there is one other area this applies to that popped up after I had written all of this article: what happens when you read a news article, and you read something in it that is completely wrong? For example, last year when Elon and Twitter were fighting in court, I’d read so many articles that would mention “Elon can walk from Twitter for a $1B break fee if he wants to.” That was completely wrong; anyone who had read the contract could tell you that Elon could not just walk for $1B just because he felt like it. So when I’d read a seemingly credible article discussing the merger or background in it that suggested that “$1b walk option,” I’d never know what to do with the rest of the article given the author was wrong on such a basic fact. I mean, the author is wrong, but it’s not like they’re lying, right? They’re just misguided. Is it because they haven’t done the work to understand, or is it because their sources are misleading them. So when the rest of the article would say “two sources close to the board think XYZ,” can you believe that piece of the article knowing how wrong something elsewhere in the article is?

PPS- I’ve taken a pretty big stand the Tennis Channel isn’t worth approaching $1b…. but it does have some pickleball rights, so maybe pickleball will have an F1 moment next year and I’ll be stuck eating crow! Anything can happen in the markets; it’s rare, but sometimes the sky does turn out to be green in finance!

This is really well done, Andrew. $IAC is another SOTP story, though management’s reputation (Joey) is stronger, and the value of assets/investments is clearly much easier to track - though the 2Q letter and overall performance were brutal.

Love the insights here! Especially about deluded management teams and the responsibility of investors to challenge and assess their thinking.

Having founded a startup and sat in a few others’ board discussions, I saw this sort of thing happen to me and my cofounder as well as others. The challenges we received saved our bacon :)