A few weeks back, I put up a post on how if you ran MSFT in reverse (I called it “Benjamin Button’ing” the investment), you would have a massive loser and anyone who held on to it would be accused of massive style / thesis drift. Instead, people who bought it as a value play and held on to it becoming a tech juggernaut have produced incredible results and are lauded despite the obvious style drift over time.

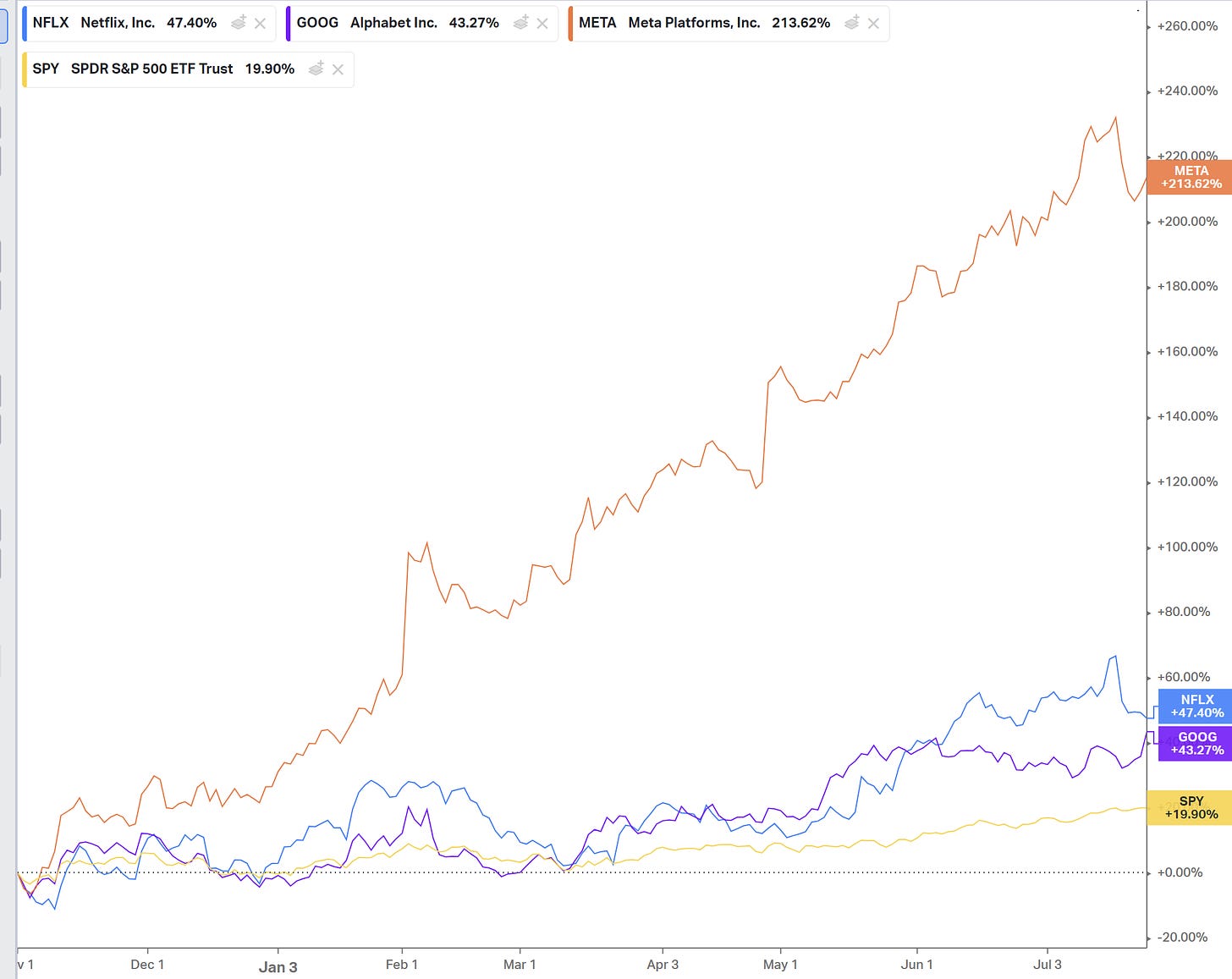

I had some pretty interesting conversations on the heels of that post. A few people noted that just about every major tech company has gotten really cheap at some point over the past decade. And not cheap in a “it’s only trading at 20x P/S and peers are at 30x” sense, but cheap in an absolute sense / when compared to market multiples. For example, my Benjamin Button post mentioned AAPL and MSFT trading for ~10x P/E in the mid and early 2010s (respectively), but just last year you had the chance to buy META at ~10x P/E with net cash on their balance sheet and/or GOOGL + NFLX at mid-teens P/E. Those stocks have been absolute screamers since (briefly) trading at those cheap multiples, which prompted the question, “is there just something about big/dominant tech that lends itself to getting temporarily cheap / presenting alpha opportunities?”

That “do these companies just lend themselves to presenting alpha opportunities” is a really interesting question, and I think it actually ties back to the Benjamin Button question.

Facebook, Google, and Netflix are all incredible businesses. They have huge scale, incredible cash flows, great talent, unmatched distribution, etc. But they are also extremely asset light businesses that can be replicated pretty cheaply. If we were just talking about the core Facebook website, how much would it cost to spin up a competitor site? Five engineers and a couple hundred thousand dollars sounds about right, no? Now, obviously that site wouldn’t stand a chance against Facebook; the real value of Facebook is in the network effect of people using it and the content constantly getting generated / created for free, but the simple fact is a competitor can be created reasonably cheaply. The same goes for Google and Netflix; yes, it would cost more than my Facebook example to spin up a functional competitor to either, but the investment needed to launch a competitor is a drop in the bucket for a large tech company versus the prize of launching a successful competitor.

That’s not to say successfully launching a competitor is easy; just that launching one is. But when you combine ease of launching with huge potential pots of gold at the end of a successful rainbow where you displace them, you can expect any stumble from an incumbent to be meet by a near immediate competitive launch. We’ve seen an example of this recently; Twitter has been stumbling / shooting themselves in the foot since Elon bought them for ~$50B, and Facebook responded by launching a “twitter killer” in Threads. I think the launch has stumbled and the product wasn’t great, but Facebook probably spent <$50m to launch threads and it had at least a shot of capturing a multi-billion market from Twitter.

Or consider another Facebook competitive launch: dating. A few years ago, Facebook announced a move into dating, and Match (which owns tinder and a host of other dating apps) shares plunged. That stock drop proved a huge opportunity for people who could look at the Facebook product and conclude it was unlikely to impact Match, but it was certainly scary in real time and lots of people thought it was the end for Match.

Facebook, Netflix, and Google’s core business all represent much more valuable markets than Twitter and Match; expect any stumble from the three to be meet by immediate competitive responses to try to make inroads.

So my suspicion is that these companies can get very cheap every now and then because investors are (rightly) concerned about how quickly their moat / earnings power can unwind. Remember: all it takes is one successful competitor to launch to seriously impair or even evaporate these business’s earnings power / value (think how valuable SNAP would be if instagram and TikTok hadn’t rapidly stole a ton of their features!). But that “shoot first and ask questions later” approach to responding to threats can present opportunities for investors who can look at stumbles / competitive responses and rightly conclude that the threat is overblown / the earnings power hasn’t shifted.

PS- I used “stumbles” in this sense to mean the company bungling their operations (as Twitter seems to be by limiting free users), but it does not have to be serious operational issues that results in doom. Consider Facebook in the early 2010s: they completely changed the business to focus on mobile and bought Instagram. At the time, those moves were controversial, but with the benefit of hindsight they were moves the company had to make. If Facebook had not switched, it would have absolutely gotten left behind / replaced. It might still be profitable today, but people would be making a ton of “Facebook was myspace 2.0” jokes. All it takes is a dominant company missing one tech window shift for them to get left behind / for someone to launch a competitive product that dominates the new window.

PPS- A fair criticism of this post would be “Almost everything gets cheap once or twice over a ten year period; what’s so unique about big tech?” I think it was You Can Be A Stock Market Genius (still my favorite investing book) that showed a bunch of large cap stocks with their 52 week highs and lows and how they were often 50% apart. Stocks tend to swing! But what strikes me about the large cap tech companies is that their sell offs were generally not “macro” driven (they didn’t get cheap for a brief second during the COVID sell off or the GFC); instead, they got very cheap because people had serious concerns with the business. And these are very well covered businesses that most of us encounter roughly every day in our lives, so what they’re doing / what’s concerning investors is reasonably knowable to most investors. It’s interesting that value can sit so clearly out in the open.

Another interesting question: to what extent do these globally dominant giants have (significant) optionality around their ability to leverage their networks, scale, and technology stacks to dominate entirely new and currently unforeseen markets?

For example, while it's yet to be determined whether META will kill TWTR (it's more nuanced than that, but I'm trying to keep it simple), META has a huge leg up by virtue of its existing networks and scale vs. that TWTR killer I'm incubating in my garage. AMZN, MSFT, and GOOG were likewise able to leverage the compute infrastructure that they had built to run their globally dominant online commerce, software, and search businesses to dominate the newly emerged cloud computing opportunity, while AAPL was able to leverage control over its closed hardware platform to create the world's largest and most lucrative services business.

Historically there has been significant attrition among globally dominant corporations. Is it different this time? Are we at a point where the networks, scale, and technology stacks of these giants makes their dominance - not just of current but also future markets - unassailable?

If true, this has wide ranging implications across many fields (economics, politics, etc.); to return to the mundane, maybe as investors we have finally reached the promised land of one decision stocks?

When the large tech stocks get cheap, it's not because people aren't aware of their network effects, It's rarely because people think someone else is going to recreate Office, or the iPhone, and compete those profits away. Rather, it's that people feel that those products for one reason or another are going to lose their salience in the future. Or, in the particular case of Meta, both that and that the CEO was setting large amounts of money on fire.