Why the low multiple series: Rental Car companies edition, part 1

Earlier this week, I introduced the “why the low multiple” series, and today we’re diving into the first industry for that series: the rental car industry.

To be honest, the industry has become a minor obsession of mine recently. I’ve kicked off every zoom / phone call over the past week with, “Hey, I know we’re scheduled to talk about XYZ…. but have you looked at the rental car companies?” I find the whole industry absolutely fascinating right now.

Why?

There are two publicly traded car companies, Avis (CAR) and Hertz (HTZ), and both are extremely cheap (as is a requirement for this series). Consider Avis: In 2022, it did ~$2.8B in net income. In 2021, it did $1.3B. They haven’t reported 2023 results yet, but Bloomberg has them doing >$1.5B of net income in 2023 (which shouldn’t be hard to hit; they did just shy of $1.4B in the first nine months of the year!).

Add it all up, and Avis will have done just shy of $6B in net income over the past three years.

That’s an interesting number, because as I write this, Avis’s market cap is also $6B.

So they’re trading for ~4x 2023’s estimated net income…. or the sum of the past three years net income if you prefer that metric.

And note that I am using net income there. That’s your after tax, after interest, GAAP net income. It’s real earnings (and backed up by real cash flow), not some hypothetical adjusted number.

Avis is using that real cash flow to absolutely shower shareholders with capital returns. In Q4’2023, they paid out a $10/share special dividend. On top of that, they bought back $240m of stock through ~December 5 in Q4, and that buyback comes on the heels of buying back ~$3.3B of stock in 2022, ~$1.5B in 2021, and ~$700m through the first nine months of 2023. Put it all together, and in the past three years Avis has likely returned more cash to shareholders than their current market cap!

That’s an incredibly powerful combo: Avis is trading for an insanely low multiple, and returning all that cash to shareholders. Every year that Avis’s earnings don’t “crack”, their shareholders get huge amounts of their market cap back in cash (whether that’s through dividends or through share repurchases that end up with each share representing a much larger piece of the Avis pie). Given the share repurchases and low multiples, Avis’s publicly traded float is shrinking very quickly, and we’ve already seen the stock have one meme squeeze before.

Now, you might wonder why Avis’s stock trades so cheaply. After all, a stock normally trades at a really low multiple to earnings when the market questions the sustainability of earnings. This year will mark the third consecutive year they’ve earned at least $1.3B; how can the market doubt the sustainability after three years in a row?

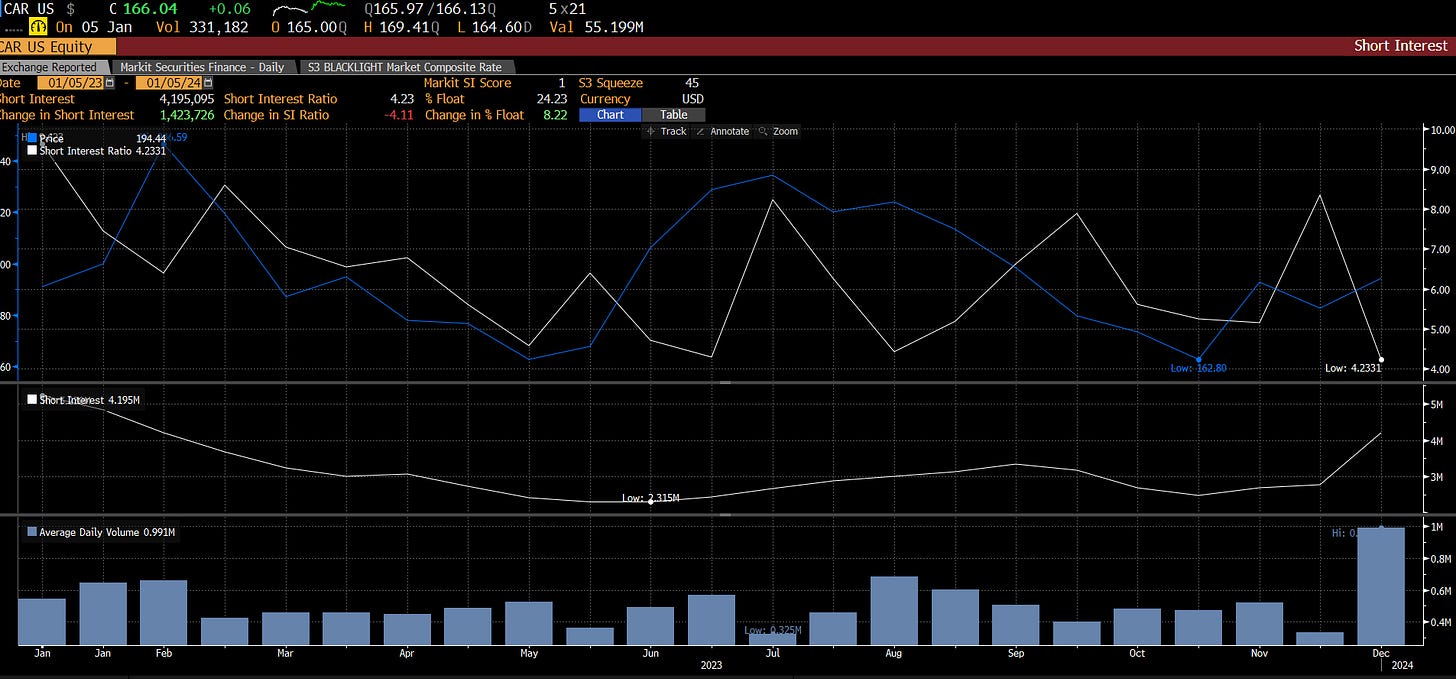

And it’s not just “the market” doubting the sustainability of Avis’s earnings; short sellers are actively betting that Avis’s earnings are set to fall off a call. Almost 25% of Avis’s free float is short, and Avis has been written up as a short three times over the past three years on VIC.

So where is the shorts’ / market’s skepticism of Avis’s earnings coming from (and Hertz’s earnings too; note that basically everything in this article applies to both Hertz and Avis, but Hertz made a bet on Elon / Tesla that has gone very wrong for them so their 2023 earnings look a bit worse due to some idiosyncratic factors…. thus the focus on Avis and their much cleaner numbers!)?

The skepticism is coming from two separate areas (though they are intertwined): the operating business, and used car pricing.

Let’s start with the operating business: there’s a suspicion that rental car companies are having a bit of a revenue windfall right now, and that will come down over time.

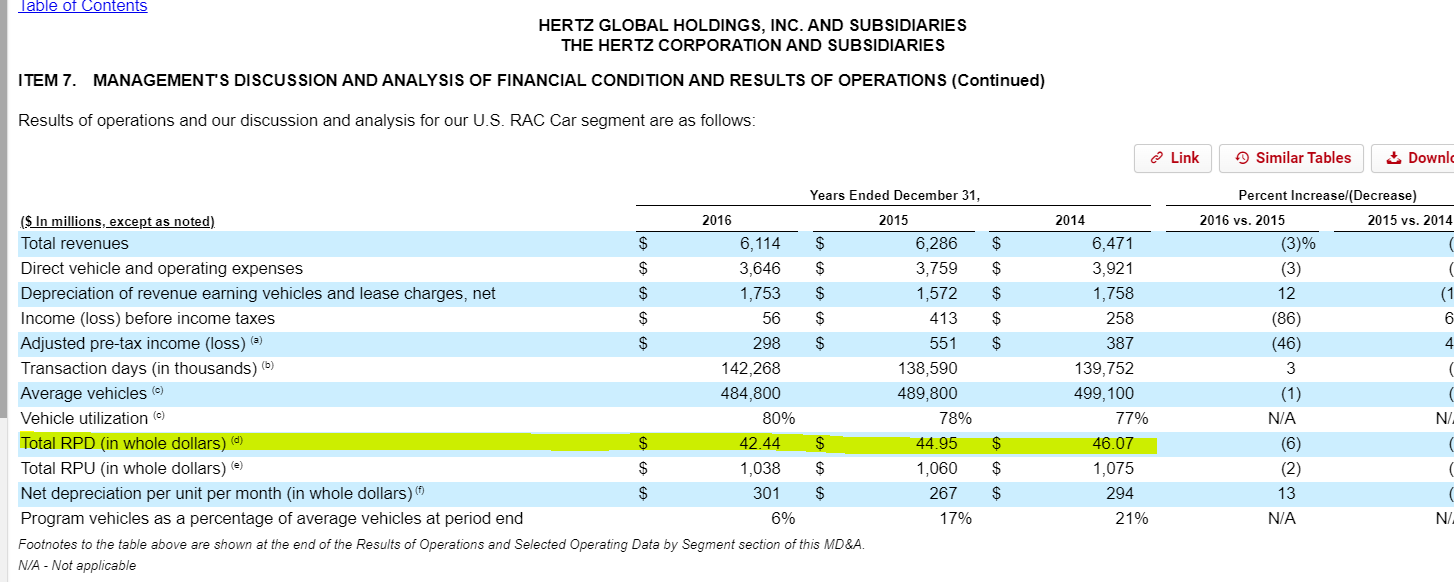

Perhaps the key operating metric rental cars report is revenue per day (RPD). RPD is basically the average revenue they get each day from renting their cars. For literally years, this number was stuck at ~$40/day. For example, here’s Hertz’s 2016 10-k showing RPD had decreased from ~$46/day to ~$42 from 2014 to 2016.

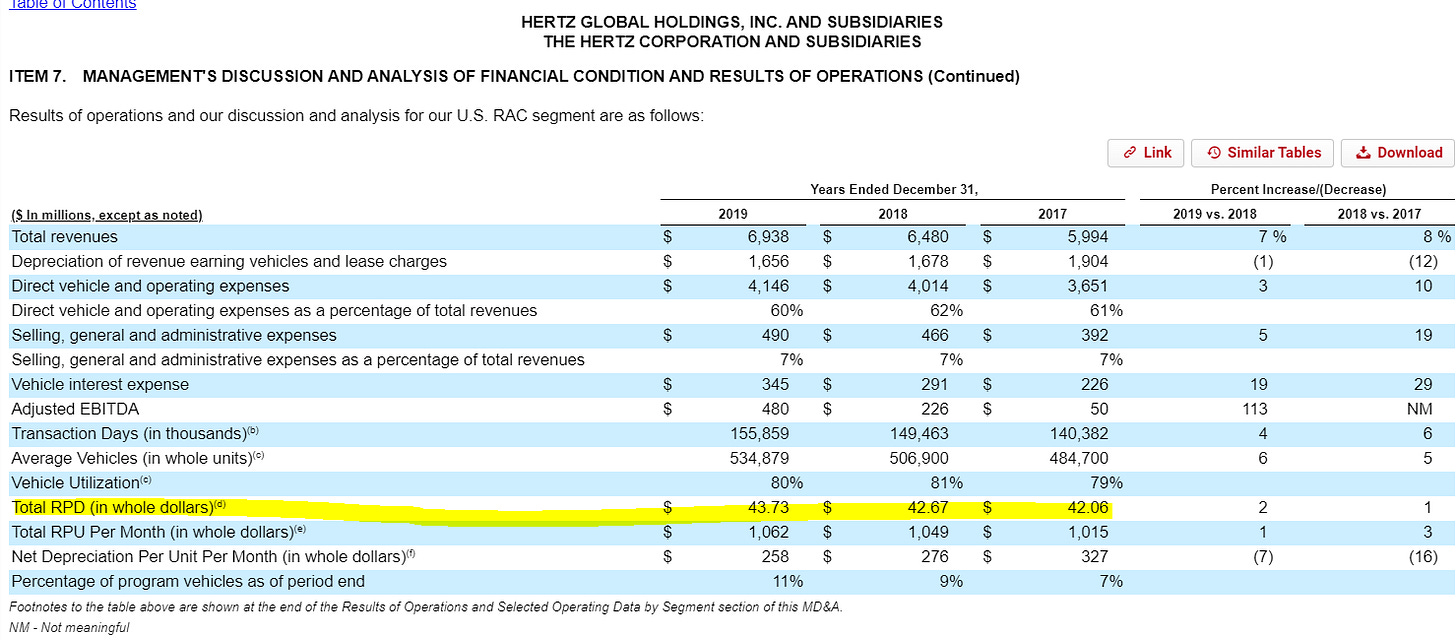

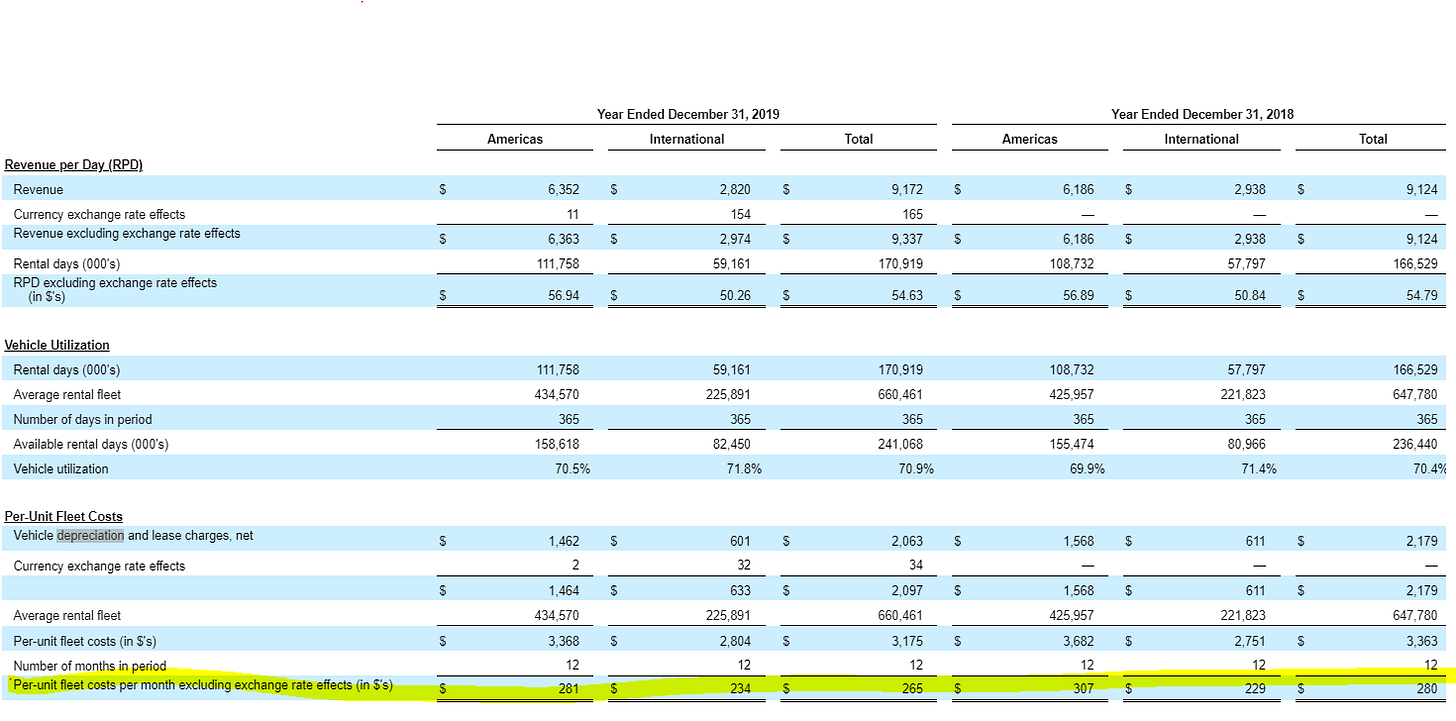

Here’s the same table from their 2019 10-K; RPD is still under $45/day (i.e. below where it was in 2014).

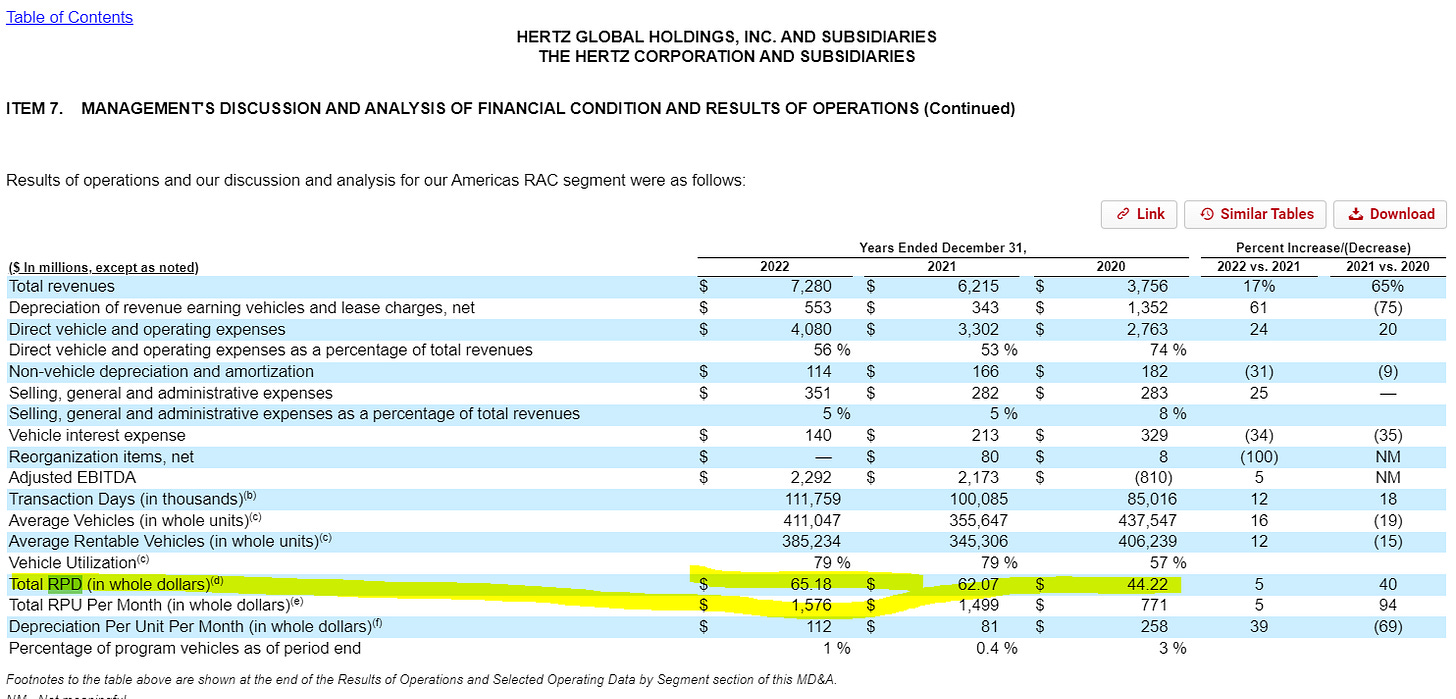

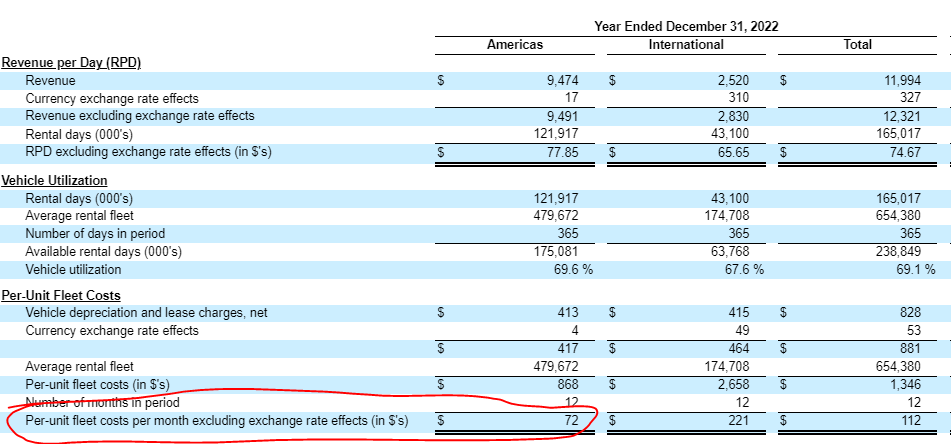

And here’s the same table in 2022; RPD breaks out (on the upside) in 2021 and has ballooned out to $65/day by 2022!

A rental car business is a largely fixed cost business (particularly in the short term); it costs Hertz (and Avis) roughly the same amount to run the network whether they’re getting $40/day/car or $65/day/car. So I think the first bear case is that the rental car companies are clearly overearning on the operating side, and as rental prices fall back down their earnings are going to collapse.

So that’s the operating side of rental cars (potential) overearning. However, the bigger piece of the bear case relates to the cost side around used car pricing, and it involves understanding a little bit of accounting.

When a rental car company buys a car, they have to depreciate the car every month. To simplify, they basically say “we bought this car for $30k, and we think we will sell it for $22.8k in two years. So it’ll depreciate by $7.2k over the next 24 months, meaning we should charge off $300/month of depreciation for this car.” And, for most of their life, that’s what happened. For example, the table below is from Avis’s 2019 earnings release; you can see in 2019 they had $281/month in depreciation/vehicle, slightly down from $307/month in 2018 (note I’m using the America’s segment, so you could accuse me of some domestic bias…. but the majority of both Avis and Hertz value comes from the America segment so I think it’s fine to focus on America!).

But that depreciation schedule is obviously an assumption. What happens if the car turns out to be worth dramatically more or less than the depreciation schedule?

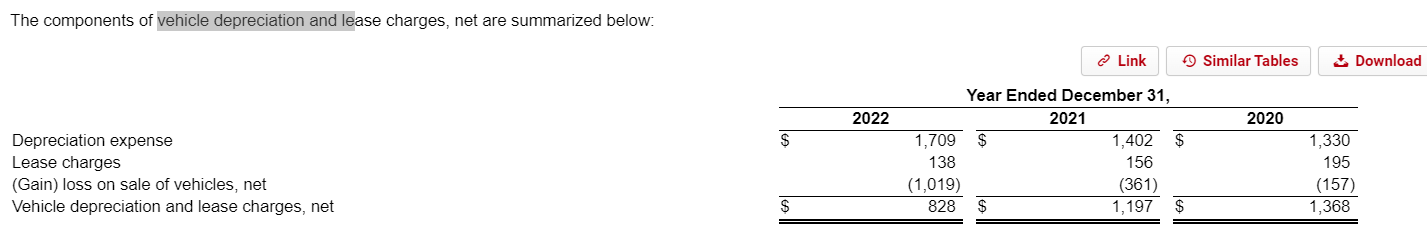

I bet you can see where this is going already; in the post COVID world, used car prices went absolutely bananas. A car that the rental company had assumed was going to sell for $22.8k might have ended up selling for $29k. When that windfall gain happens, the rental car reports a gain on the sale of vehicles (in that case, a gain of just over $6k), and the gain offsets their depreciation during that period (so, in my example, Avis would report a ~$6k gain on the sale of that car and use it to reduce that year’s reported depreciation expense). So, for example, in 2022, Avis reported $1.7B of depreciation before sale of vehicles….. but they realized just over $1B of gains on vehicle sales (chart below from F-28 of their 10-K), so their net depreciation number came out to just ~$800m (including $100m in lease charges).

Those gains have resulted in some wild depreciation numbers; in 2022, Avis reported depreciation of just $72/month/car in the Americas segment.

So your bear case is pretty simple: earnings today are wildly inflated by COVID tailwinds that have yet to unwind. You have wildly inflated rental prices on the revenue side, and wildly understated costs on the depreciation side thanks to the current used car bonanza. If and when both of those reverse, earnings drop in a hurry.

How much would earnings drop? Well, sticking with Avis, in 2019 (i.e. before the pandemic), the company did ~$300m in net income. If Avis instantly dropped back to that level of earnings, it would be trading for >20x P/E. Not exactly cheap… and Avis had just ~$2.7B in net corporate debt then versus ~$4.2B today. Combine that higher debt burden with higher interest rates, and I think it would be fair to say Avis’s net income in a similar earning environment would be closer to $200m on today’s cap structure / interest rates, which would put Avis >30x on their “2019 interest rate / cap structure adjusted earnings” multiple (if that’s a thing; it’s not, but I’m sure you get what I’m saying).

And things would get even worse if used car prices really roll over. I’m slightly paraphrasing / twisting them, but two popular sayings in markets are “the cure for high prices is high prices” and “I’ve never seen a supply shortage that’s not followed by a glut of supply.” Markets work… and when you’ve seen >3 years of record used car prices, it’s not crazy to think used car prices might overshot to the downside. What if some of those cars that Avis has been depreciating to $22.5k and selling for $29k (in my example) all the sudden started selling for $20k? Suddenly Avis is reporting loss on used car sales, which will cause their depreciation to shoot past their steady state numbers and prove a huge drag on earnings (and cash flow).

And those are just the financial bear cases! You could dream up tons of other bear cases; both Hertz and Avis use the ABS market to finance their rental fleet (and it’s a substantial amount; Avis has ~$18.6B of vehicle debt versus $6B in market cap and ~$4b in net corporate debt ); ABS borrowing is generally a pretty safe way to borrow but you could imagine all sorts of tail risks associated with it (after all, a margin call on used cars / ABS freeze is part of what sent Hertz into bankruptcy during the pandemic). Or you could start getting even farther out there; both Hertz and Avis’s rental fleets are largely ICE (i.e. gasoline) vehicles. What if you saw a massive acceleration to EVs? That would kill the resale value of Hertz and Avis’s fleet. What if we have a breakthrough in robo-taxis and autonomous driving; some people think rental car companies are a key strategic piece of that world, but it’s very possible (in fact, I think more likely!) that they’re a complete zero in that world as well.

I’ll admit it…. when I started researching the rental car companies, I kind of thought “ahhh the bear case is kind of silly; rental car companies have posted record-ish earnings three years in a row. If that’s not the sign of an industry that’s shifted for the better, then what is?” But after putting the bear cases to paper, you can see just how serious the concerns are.

So is there a bull case?

Yes, absolutely…. but you’ll have to wait till part two later this week to for it. See you then! (editor’s update: part 2 is now live here)

PS- I’ll discuss this more in part 2, but it is worth explicitly noting that the two areas of rental cars overearnings (high RPD and gain on used car sales) are related to each other. There were obviously lots of factors causing both, but the main one was a new car shortage. The new car shortage caused used car prices to spike as used car prices are inexorably tied to new car prices, and the new car shortage meant that, even if they wanted to, rental car companies couldn’t respond to the rise in RPD by buying new cars (and thus increasing supply in the rental car market) because there simply wasn’t any supply to buy!

This series promises to be awesome!

As always, thank you for sharing your thoughts.

Great first article in this series! Really enjoyed reading it and shows the difficulty in trying to normalise earnings!