$YELP's Quarter Got Negative Reviews, But It Could Be A Five Star Opportunity

This post ran a bit longer than I would have liked. Normally I’d try to trim the post a bit, but it’s Thanksgiving week and in the spirit of Thanksgiving I’m going to leave all the “fat” on this post. To sum it up: I’m long Yelp, and believe the recent sell off presents an attractive opportunity to buy the company at a discounted multiple despite signs of accelerating user engagement and significant margin expansion potential. As always, I welcome feedback: please feel free to leave a comment or hit me up on Twitter if you have done work on Yelp and agree/disagree/think I’m missing something. One of my core investing beliefs is that a lot of investing is about pattern recognition. Not in the technical charting “head and shoulders” type pattern way, but more about developing some “mental models” over time where certain things make you pay attention and think “hmmm….. there could be value hidden here / something the market is missing”. The old “insiders sell for a lot of reasons but only buy for one reason” (suggesting insiders could sell for a variety of reasons, including divorce, taxes, paying for their kids’ college bills, etc. but the only reason they buy their stock is because they have great insight that the company’s value is higher than the current price / think the stock market is undervaluing the company) is a very simple / classic example of this type of pattern recognition. Over the past few years, there are two specific patterns that I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about and looking for:

Companies who are making big income statement investments that are depressing their income statement in the short term but that will produce positive risk adjusted returns (aka forgoing short term profits for long term returns). A perfect, if simplified, example of this type of income statement investment is R&D expense: companies increase R&D spending at the “expense” of today’s P&L with the hope of generating significant returns long term. That’s a simple one, but there are plenty of more complex ones:

Probably the most famous recent example of this is “pulling an adobe”, where a tech company will switch from a product sales model to a subscription model. Pulling an Adobe absolutely demolishes your income statement in the short term (if you previously sold a software license that lasted for 3 years for $100 dollars up front, you’re probably signing people up to annual subscription licenses for $40/year so your revenue drops by double digits for a few years while your cost base stays flat), but it generally leads to more pricing power, stickier customers, and a whole host of other benefits.

Another interesting example today is Disney. Disney is forgoing literally hundreds of millions of dollars of basically pure profit by pulling their movies from Netflix and building up their direct to consumer service. In the short term, that depresses their income statement, but the hope is in the long term building a DTC business creates billions in value for Disney.

There are literally hundreds of other examples of forgoing short-term profits for long term returns (most of them tech focused). Many of Amazon’s best businesses have come from a willingness to make these types of income statement investments. Consider their decision to continuously lower prices for customers (as they discussed in their 2005 annual letter): in the short run, lowering prices always hurts Amazon’s income statement. However, in the long run, it gave them a “virtuous cycle” of scale economies that no competitor could match.

Maybe this seems like too obvious an area to focus on, but consider this: as we speak, Disney is undergoing one of the largest media mergers in history (with Fox) while prepping to launch multiple direct to consumers apps. So it’s a bit of an understatement to say there’s a lot of interesting stuff going on, yet somehow the question analysts spent the most time on on Disney’s most Q2 earnings call was the accounting for the DTC service. As an investor, does it matter if it’s a balance sheet investment or expensed immediately? Isn’t it a bit more relevant to try to figure out if the investment is actually good and will create value versus how it will be accounted for? (Bonus analyst shenanigans on the DIS call: one analyst wasted time asking an investment grade company w/ $4B in cash on their balance sheet and ~$10B in annual FCF about their <$1B in near term maturities)

The other thing I like about “income statement” investments is they fit well into my mental model of markets today: the “easy” money of buying things simply because they are cheap (“hey, this trades below book; let’s buy it and sell it when it trades up to book”) is for the most part gone / has been competed away by computers. If you’re looking for an edge, you need to find something computers can’t pick up on, and intentionally depressing reported profits in the short term for a long term benefit is the exact type of thing that a computer model or algorithm would have difficulty picking up on.

Look for companies where you would 100% believe a rumor that the best strategic company / investor in that sector had agreed to buy them out. An example might be best here; let’s say you think Warren Buffett is the best buyer of legacy consumer brands out there. If someone came to you tomorrow and told you he was buying out Under Armour, would you believe them? If so, then Under Armour is probably worth doing some work on as a potential investment. If not, Under Armour probably isn’t that interesting of an investment.

That’s obviously one example involving an investor looking for a long-term compounder / buy and hold forever stock. You could apply the same logic to all sorts of situations. For example, if you’re looking at a potential activist type situation, just ask yourself if you would believe a headline that said Carl Icahn had gotten involved in the company and was pushing to do something (block a bad deal, push for a bump, push for a split, etc.). If you would believe that headline, than the company is probably worth thinking about as an activist candidate. If you wouldn’t believe it, there’s probably not an activist play there.

The reason I mention both of those “patterns” is over the past ~6 months one of the companies I’ve been thinking about the most is YELP (Disclosure: long) and I think it fits pretty squarely into both of those buckets. I first started looking at YELP when someone pinged me and suggested YELP would be a perfect acquisition fit for IAC (disclosure: long) to either buy out or merge with ANGI. When they said that and my first thought was “o that makes tons of sense; this would be a perfect IAC / Barry Diller company“, YELP had ticked off the second pattern pretty easily (I have enormous respect for Diller; though ultimately I doubt IAC / ANGI buys Yelp as after some more work I don’t think it fits their model squarely). And, as I’ll discuss in the post, YELP also fits well into the first “pattern” as well: the company has been making a massive investment in their business that has lowered their near-term revenue base and increased their cost structure but should produce significant long-term returns. I’ll start with a quick overview, as I’m guessing most readers know Yelp. Yelp is a consumer review site focused on local businesses. Yelp is particularly known for local restaurants reviews and discovery; however, the company offers reviews of all types of local businesses.

Source: YELP 10-K

YELP’s business is pretty simple: consumers review and discover businesses on YELP, and YELP offers businesses tools (mainly advertising) to reach out to consumers who are using YELP to discover businesses (i.e. if you’re looking for a Chinese restaurant, the local Chinese restaurant will pay YELP to for a promoted slot that puts them at the top of your search). The overall thesis for YELP is pretty simple: it’s one of the most downloaded apps in the U.S., with more than 34m monthly active devices, the company is growing quickly, and they have significant optionality given their reach and frequency of consumer usage.

Source: YELP Q1’18 Shareholder letter and YELP Q4’17 earnings slides

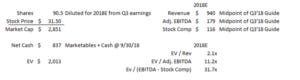

The significant optionality piece is worth diving into. One of the investment theses I’m really interested in is usage frequency: there simply aren’t many apps that consumers use and open every day, but the ones that consumers do have significant optionality to expand into other verticals. Facebook and what they did with Messenger is probably the best example of this: Facebook had an app that people used daily, and they used that frequency to roll out messenger within the Facebook app and then, when it had enough usage, pushed messenger into a new app that is now one of the most downloaded apps in the world. Yelp clearly isn’t Facebook (and the Facebook Messenger launch required a social dynamic and network that Yelp could only dream of!), but Yelp does have a very common frequent use case (reviewing and discovering local restaurants, something that most users do multiple times per month), and having consumers who use and open up the Yelp app multiple times per month to review restaurants gives Yelp a ton of optionality to do new things; for example, Yelp can go deeper into restaurants (they are currently expanding into restaurant reservations and wait lists) or they can try to push restaurant searchers into other search areas (“hey, did you know you can see our reviews of local plumbers too?! We’ll even let you book the highest rated one now!”). If Yelp can hit on any of that optionality, the potential upside is huge. However, we’re not really paying much for that optionality; at today’s prices of ~$31.50, YELP trades for ~11x their estimated 2018 adjusted EBITDA, which is a bit below where most internet peers trade (though given different levels of current investment, scale, life-cycle, etc. it’s tough to compare multiples across companies). Obviously, Yelp’s Adjusted EBITDA estimate contains a huge stock comp adjustment, but so do Yelp’s peers EBITDA so I don’t think it makes valuation comparisons impossible.

Gun to my head, I’d say Yelp’s EBITDA number is conservative for a few reasons:

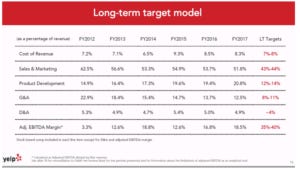

Yelp's Adjusted EBITDA margin today is <20%; that just seems way to low for a scaled internet player. It’s tough to point to an exact comp for YELP, but TripAdvisor’s non-hotel segment is as good as any and currently has >30% adjusted EBITDA margins. ANGI Homeadvisor is another decent one given Yelp’s expansion into request-a-quote, and they have consistently guided to 35% Adjusted EBITDA margins at scale. OpenTable has some similarities to YELP as well, and was projecting >35% EBITDA margins when they got acquired by Priceline (see p. 24). So just a rough look at their loose peers makes me think YELP can and should do better than <20% adjusted EBITDA margins in the long term, and to value them on today’s margins is unfairly punishing them.

Obviously those are some very loose peers; most of them are much more transaction focused.

On the lower end, I’d guess the Knot (“yelp for weddings”, ticker: XOXO) should have structurally lower margins than YELP for a variety of reasons, but they are doing >20% EBITDA margins currently and targeting close to 30% margins as they scale up (see p. 43); they also just struck a deal to get bought out for more than >22x adjusted EBITDA (see p. 38) so I would happily settle for their margins if I got their multiple too!

YELP themselves have argued that they could scale to 35% adjusted EBITDA margins before; the below is from their Q4’17 earnings slides

Yelp is investing in some startup concepts (Nowait, WiFi, reservations) that will burn ~$25m in EBITDA in 2018 (see Q1’18 call, and they’ve reaffirmed that number as recently as at the RBC conference in November). The hope is that these investments are both directly profitable (i.e. those businesses are eventually profitable enough on a direct basis to justify having invested in them) and profitable to the overall Yelp ecosystem (the added user engagement from having consumers use Yelp more frequently to book reservations or waiting list spots improves the overall value of Yelp), but if not you’d assume the company could shut that investment down and it would represent a onetime type of expense. Adding those losses back alone would reduce Yelp’s multiple by more than a full turn.

Yelp has made a massive investment into headcount over the past few years, growing sales headcount from ~2,500 sales people at the beginning of 2017 to 3,700 salespeople today. It takes some time for a sales rep to ramp up, so in the short term Yelp carries a bloated cost base as they hire new sales people but it should improve revenue growth in the long term (I like how YELP put it on their Q2’17 earnings call: they noted headcount was up ~50% year over year, and that they weren’t increasing staffing 50% just to get a 20% revenue growth number).

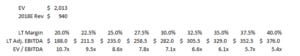

So, I believe YELP’s EBITDA margins should be structurally higher than today’s levels. I’m not sure what the end game is, but I’d be surprised if they couldn’t approach ~30% over time. If we assume that margin number is right, then YELP’s currently underearning by ~$100m EBITDA as they invest in their business and their “investment adjusted” EBITDA rate is ~$282m. The chart below shows what Yelp’s LT EBITDA level and EV / EBITDA multiple would be assuming different margins and today’s revenue rate. Yes, there are lots of assumptions in there, and we probably need to deduct for the very real stock expense that adjusted EBITDA ignores, but the bottom line here is that Yelp is trading cheaply on their current earnings base and is trading very cheaply once adjusted for what their long-term margin / cost structure should look like.

Just to wrap up the key points to the investment thesis I’ve hit on so far:

Yelp is one of the most popular and frequently used apps out there, and that gives them significant upside optionality to monetize their user base.

Yelp is currently investing into both their product and their sales force, so their margins are well below where they should be once the company fully scales up. If we adjust their margins to their likely long-term levels, we are buying YELP at a very low multiple

Even without that margin boost, YELP is trading decently cheaply. The company is projecting double digit revenue growth next year (along with 2-3% EBITDA margin expansion); it’s pretty rare to find an internet company (which is inherently asset / capex light) that’s growing double digits and trades for a low double-digit EBITDA multiple.

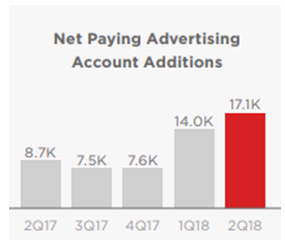

Alright, hopefully that’s a good overview of the investment thesis. Let’s turn to the reason why I think the investment opportunity exists: the shift to non-term contracts and the disastrous Q3 results / Q4 guide that saw shares plunge by ~30%. Those reasons are actually relatively intertwined, so let’s start with an overview of non-term contracts and then talk about the awful Q3 and why I think there are plenty of green shoots in it. Heading into 2017, Yelp only offered “fixed-term” contracts. Basically, if you wanted to get an ad on Yelp, you needed to shell out $3-4k to buy one year of advertising. Last year, the company started testing a non-term contract that would effectively let advertisers buy by the click or by the month (what they call “non-term” contracts). The switch was risky: while lowering the dollar commitment should increase the number of potential advertisers (seasonal businesses probably aren’t buying yearlong ads but may buy by the click during peak season, a yearlong commitment may be too pricey for many small businesses, etc.), switching from year long contracts to monthly substantially increases churn and makes results substantially more volatile (if you’re month to month and a depression strikes, you can just stop paying monthly but if you prepaid yearly you’re locked in). The early results from the switch to non-term contracts were really positive. Yelp started adding advertisers at a record clip (in the first half of 2018, they added as many advertising accounts as they had in the preceding five quarters combined; see chart below), and their Q2’18 shareholder letter includes quotes like “we’re pleased with how the transition has gone”, “clients have responded well to the transition (to non-term),” “non-term is helping our local salesforce,” and “the contribution-margin of local non-term deals have been consistent with those realized from term contracts in the past”. On the heels of these positive results, Yelp increased their full year 2018 guidance in both Q1’18 and Q2’18.

Then Q3’18 happened. Yelp’s net new advertising account additions slowed to zero due to new account ads well below their forecasts (cancellations increased due to the switch to non-term, but the increase in cancellations was anticipated and in line with their expectations; it was the lower than forecast ads that hit them). In response, Yelp significantly lowered their full year guidance. Generally, I’m not one to harp on guidance, but I use it here to show just how disastrous and unexpected Q3’18 was for Yelp. Yelp raised full year guidance in both Q1 and Q2, and then in Q3’18 they needed to take their full year guidance to the low end of what they were forecasting at the beginning of the year. That’s an insane guide down; in general, management teams build a bit of margin of safety into their guidance, so for a management team to take guidance up twice and then need to lower below their original forecasts is borderline unheard of and raises questions about management’s grasp of the business / ability to manage and budget the business (and, given you’ve already booked ~7 months when issuing full year guidance in Q2, speaks to a pretty awful Q3 and Q4!). Management said there wasn’t “a single or predominant factor” that led to the shortfall in net new account additions, but “rather a combination of smaller operational factors” that “crystallized in the second half of Q3” (remember, they had raised guidance after issuing Q2 earnings in the middle of Q3, so the impact had to happen in the back half of the quarter unless you want to get into real management credibility / trust questions where they outright lie on a call). I’ve included several of the issues they blame the quarter on and my thoughts on them below:

Slower-than expected sales head count growth: Veteran sales reps had a hard time moving to the non-term model and left. Low unemployment / a strong hiring environment made it difficult to hire as many new people as they wanted.

My take: Completely unbelievable. I don’t doubt either of these are true, but for them to cause this big a drop (particularly given they are arguing the drop was focused on the back half of the quarter) is insanity. I’d also note they’ve argued for a long time that new reps take a while to ramp up, so for Yelp to argue hiring slightly fewer new reps than they expected had more than a marginal effect is crazy.

Change in advertising promotions: promotions used to be a flat upfront credit (“try yelp advertising; here’s a $100 credit”), and Yelp switched to a bonus ads “dollar for dollar” structure (“for every dollar you spend on Yelp in your first month, we will match it up to $100”). The dollar for dollar structure has higher life time value but lower starts volume.

My take: makes complete sense (you’re going to get a lot of people trying your product who have no intention of continuing it when you give a free trial; requiring them to put some “skin in the game” probably leads to much better leads on the trials) and probably good for the company longer term

Technical Issue in flowing leads to reps: issue with the way new business additions to Yelp (i.e. new businesses that claim their Yelp page) were being captured and delivered to the sales force.

My take: Believable, but raises a ton of questions about management’s ability to manage effectively

Lower success rate in contacting business decision-makers by outbound call: business / account owners are picking up the phone less than they used to.

My take: Ludicrous. I don’t doubt people answer the phone less today than they did three years ago, but this should be a factor that slowly impacts them over several years. In effect, they are saying that people started picking up the phone dramatically less in the back half of Q3 than they were in the front half. That’s insane.

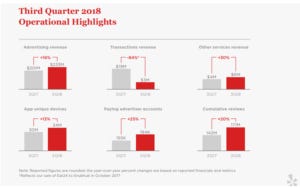

If half of the excuses were some form of bullshit, why am I not more worried? There are several reasons; for example, management mentioned they’ve seen these types of problems in the past, but the effects have been stretched over a full year due to the annual contract model. With non-term, the effects are more concentrated / volatile because churn is higher and more businesses are needed to replace the churners, which makes plenty of sense to me. But the major reason I’m not more worried is that while the company is clearly struggling on the advertising / revenue side, the evidence suggests that consumer engagement remains extremely high, and I’m betting that as long as consumer engagement remains high the company will eventually be able to figure everything else out. When I look at the non-financial statistics for Yelp like app unique devices (how many phones the yelp app is downloaded on), cumulative reviews (total number of reviews on Yelp), and claimed businesses (businesses that have claimed on Yelp) and see them continuing to grow at their historical double-digit year over year rate, I look at Yelp and see a business that is struggling with a near term sales / revenue problem and not an actual use problem.

There are even signs that the recent investments Yelp is making into in new products is accelerating consumer engagement. At the RBC conference in November, Yelp’s CFO noted that “searches per user, ad clicks per user, reservations per user, Request-a-Quote per user, phone calls per user… all of those things are growing faster than the growth rate of overall users. So, the level of engagement per user continues to increase” (later they would say those engagement levels are growing at ~1.5x the rate of users, with Request-a-Quote growing 4-5x the rate of users and reservations / waitlist growing ~10x). My bottom line here is that I believe a growing user base / user engagement is more important to Yelp than this quarter’s revenue level. Ultimately, if Yelp is attracting users, they’re going to be able to figure out how to monetize them. At today’s prices, Yelp is being priced like a declining internet property, but the user engagement trends suggest the company has a bright future in front of it. Given the low valuation, the accelerating usage, and the margin expansion potential, I think Yelp’s upside is significantly higher than today’s share price. Other odds and ends

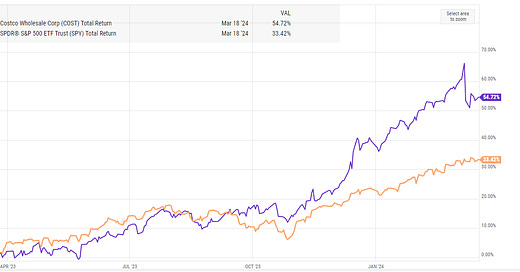

Returning for a second to the pattern recognition theme, many of the recent “wins” I’ve seen in the consumer internet space have come from investors will to look through poor short-term results at a company and instead see promise in improving user engagement metrics. For example, Twitter’s financials in 2017 were disappointing, but the product was seeing increasing user engagement (I’m using Daily Active Users as a proxy for engagement here). Twitter’s financial metrics eventually caught up to the increased engagement, and the stock more than doubled. Tripadvisor had similar issues over the past few years, as an ill-fated attempt to move into instant booking and some advertiser pullback resulted in poor financials. However, user engagement remained relatively strong, and the stock has soared as the financials have stabilized / turned around.

Both Twitter and Tripadvisor are obviously unique cases with much different fundamentals. But my “pattern” here suggests that buying an internet company with accelerating user engagement at a cheap enough price when the market is frustrated by near term financial volatility sets an investor up to do very well.

I didn’t spend much time on Yelp’s Request-a-Quote (RAQ). Request-a-Quote lets users request a quote for some type of service (a mover, a plumber, etc.) and have professionals respond with a quote for that service; the service is growing rapidly (it exited Q4’17 at an $18m annual revenue run rate and exited Q3’18 at a $45m annual revenue run rate), which is fantastic. The reason I didn’t spend a ton of time on it is I think the actual user engagement levels are more important than how the company ultimately monetizes (RAQ is great and makes total sense, but Yelp’s success is ultimately dependent on the consumer engagement so it’s more important to focus on that).

The “disaster” of a Q3’18 isn’t the first time the Yelp’s stock has plunged on bad earnings; the stock plunged after Q1’17 and Q2’15 as well. Adjusted EBITDA has grown from ~$70m in 2015 to $157m in 2017 and ~$189m in 2018. There’s obviously some questions on the management team given those big drops have generally been caused by forecast misses related to internal issues, but if you look at the bigger picture those big drops have generally been buying opportunities and the company has grown pretty strongly through them.

I mentioned Yelp’s sales force as a current cost drag that will likely result in future profitable growth as the new sales reps mature, but I think their sales force is interesting from a strategic perspective as well. At the end of 2017, YELP (an entirely domestic site) had 5.2k total employees and 3.3k salespeople. At the same point in time, Tripadvisor had 3.2k total employees (only half were domestic), booking.com (formerly priceline) had 4.2k domestic employees, and Homeadvisor / Angie’s List had 3.9k employees. So Yelp’s total salespeople count often matched or surpassed their (loose) competitor’s total headcount. You could see that being interesting to a competitor in two ways: first, a buyer could simply look at Yelp’s sales force and see a TON of cost synergies (i.e. buy YELP, fire half their salesforce, and then the combined business has a significantly larger sales force than your original business did as well as a much lower cost structure than the two businesses did separately; this would be a likely playbook if they were bought by a private equity company). I could also see a potential buyer looking at YELP and ascribing value not just to Yelp’s traffic / customer base / earnings but also assigning some value to the potential growth boost they could get from feeding their product through Yelp’s sales force (for example, ANGI could use the Yelp sales force to push more local home services businesses on to Homeadvisor).

The recent share drop could be an opportunity for some combination of an activist or an increased share repurchase program.

Activist: Yelp’s shares are cheap enough (and insider ownership low enough; despite being founder led, insiders own just ~9% of Yelp’s stock) that an activist could step in here. They could push for a sale or an optimized balance sheet (aggressively use all the cash on the balance sheet and take on a reasonable amount of leverage to buy back a huge slug of shares). I don’t think there’s an obvious strategic buyer of Yelp, but (as mentioned above) someone could convince themselves there’s strategic optionality in the sales force and their huge user base, and private equity interest in the space (the knot, WebMD) has been decently high so I think there would be some interest if an activist tried to push a sale. A really aggressive activist could push for a management shake-up: Yelp’s still led by its founder, and given the continued execution issues I don’t think it’s insane to argue Yelp could use some fresh blood, though I’m generally of the opinion a longer term look at Yelp shows management is doing an alright job (navigating the desktop to mobile switch isn’t / wasn’t easy, and the company’s grown EBITDA from basically nothing a few years ago to approaching $180m this year despite the switch and continued competitive interest from a variety of large tech players (facebook has launched at least two, Google’s been trying to go after Yelp with google maps and a variety of other things for years to the point where Yelp has argued for regulation of google).

Share Repurchase: This could tie into the activist angle above, but I wouldn’t be surprised to see the company get aggressive repurchasing shares given the recent decline in share price. The first half of this year was really the first time the company has ever been even modestly aggressive repurchasing shares (buying back shares in the low $40s), and management strongly suggested on the Q3 call that they’d take advantage of the share price decline post earnings to retire shares. In fact, if you look at p. 37 of their 10-Q, you can see they bought back 1.3m shares at ~$43/share in October. That’s a decent slug of repurchases for a company with ~90m shares outstanding; with shares currently trading at ~$31.50, I’d hope they continue to be aggressive repurchasing shares into year end. Even adjusting for those repurchases, their balance sheet is strong enough that they could easily repurchase 20% of their shares without batting an eye (if they wanted to get really aggressive, they could employ a sensible leverage policy and use the proceeds to really get aggressive buying back shares).

The move to non-term seems to have made the business a bit more volatile, but I think the move made sense in the long run (selling year long commitments for online advertising businesses certainly isn’t the norm in 2018!) and I think that’s what matters much more than some short-term volatility.

I focused this write up on Yelp’s valuation versus its adjusted EBITDA. Obviously stock comp is a real expense and it represents a huge piece of Yelp’s adjusted EBITDA. You can adjust for it however you want; I think if I’m right and Yelp can grow significantly over the next few years while expanding margins, they’ll get significant leverage on their stock comp expense and they’re cheap whether you look at them including or excluding stock comp. Reasonable people can differ though! I’d also note that in a real downside case where growth stalls out, Yelp would likely cut headcount and significantly cut their stock comp.

Might as well note here that Yelp’s capex number isn’t huge, but they do have some capex and they capitalize some software R&D, so you need to adjust for that if you’re doing your own valuation and going down to a free cash number.

Risks

There are several risks here. I think competition (discussed below) is the most obvious. But the biggest risk I see is how effective Yelp’s ads actually are. It’s not a great sign that Yelp’s ads are so dependent on the salesforce pushing them that when their salesforce growth slows just a bit their revenue growth is seriously impacted.

Yelp has guided that ~10% of their revenue comes from self-serve channels (source: November RBC conference); the company is focused on increasing self-serve’s share (which makes sense; no salesman = higher margin) but it still seems strange to me that the company needs such a large sales force. If the product is generating a good ROI, shouldn’t that be obvious to the advertisers / advertisers should be signing up on their own without a salesperson holding their hands?

I think the counter to this is a lot of Yelp’s value comes in things that aren’t directly measurable. When you buy a google ad, you can generally track how many people buy after seeing that ad because they are buying online (and often immediately after seeing the ad / clicking on that link to buy). The end result from a Yelp ad is often an in-person visit; it can be really difficult to quantify digital ads’ effects on real world visits / interactions. I’m sure Yelp would argue the salesforce is necessary to help quantify the returns from that advertising, but I’m a bit skeptical.

Another counter- Yelp is selling to small local businesses that often aren’t super sophisticated. It’s easy for google to be mainly self-serve when most of their customers are highly tech savvy, but Yelp is trying to get the local restaurant (which may not be super sophisticated when it comes to tech or marketing / may still be relying mainly on paper mailers) to advertise online. Perhaps some handholding really is necessary here.

A personal example might show some of the issues I see here: I live in NYC by Grand Central and just pulled up “restaurants” on Yelp. The first ad I got was for Mocana Bakery located at ~145th and Riverside. That is a really long way away (for my Non-NYC readers, it’s a ~45 min subway trek or a ~$20 uber to get there); somehow, I feel like a low budget bakery with a 2-star rating (on just 4 reviews!) advertising to people almost an hour away isn’t the best use of their advertising budget. Again, this is just one example, but getting shown that ad suggests to me that Yelp’s targeting is really poor or there’s very little competition for ads (perhaps both). (Of course, this could suggest a lot of upside as Yelp’s advertising market gains scale and they can improve targeting with better advertising depth, or perhaps I was just shown this ad because Mocana was trialing the service and spending unwisely on their “free” trial dollars)

The most obvious risk here is competition. Google and Facebook are the big competitors that immediately come to mind, but there are plenty of others (foursquare, tripadvisor, opentable, etc). I think the big “competitive” risk can be broken into three types: legacy product devours yelp, larger product transforms into yelp, or new product overtakes yelp.

New product overtakes yelp- someone launches a flat-out Yelp competitor that “eats” yelp. Unlikely at this point, though barstool sports is trying.

Legacy product devours yelp- Something like Google Maps continues to roll out Yelp like features (and they’re definitely trying) and eventually overwhelms Yelp. Possible, and absolutely a scary source of incremental competition. Still, it’s tough for google maps (which is generally used for finding location / directions) to replace Yelp (which is focused purely on discovery and reviews).

Here’s a former head of YELP design responding on how they managed to fight off competitive products. I’d note that google maps has been trying to take on Yelp for years.

Larger product transforms into yelp- This would involve something like instragram transforming into the new way to find and review restaurants. Again, possible, and a scary source of incremental competition, but I think Instagram would be way too crowded for using exclusively for reviews and discovery like yelp generally is. (Below are some articles that shows Instagram as a potential / incremental competitor)

These are all obviously risks, but I think as we move further into an app dominated world the risks actually go down. Consumers with Yelp on their phones now instinctively go to YELP to post and see reviews; once you’ve gotten that type of consumer habit ingrained it’s very difficult for a competitive product to usurp that.

Another benefit of this switch from desktop / window viewing to apps is as people get more in the habit of using the Yelp app for reviews versus searching, Yelp’s dependence on Google goes way down.

At RBC in November, YELP mentioned that they were getting >50% of their traffic from search engines ~three years ago; today, that number is ~25% and the vast majority of views are viewed inside Yelp’s app.

I think I hit on the above point in the write up, but just to spell it out a bit more: in the old days, most companies got their traffic from Google. That’s still an important point of traffic but today what really matters is being an app downloaded on someone’s phone and having the consumer habit of opening that app up for certain tasks ingrained (i.e. when I want to find a new restaurant, I immediately pull up Yelp).

Also, while we generally think of Yelp for restaurants (and they openly admit they use restaurants as the hook to lure people into their ecosystem), Yelp actually makes most of their money from non-restaurant categories. It’s tough to see Instagram or Google Maps taking Yelp on in those categories (no one is going to look for a local plumber on Instagram (though it is funny to imagine what a search for local plumbers would yield on instagram), and if you’re looking for a new plumber I doubt your first instinct is to go to Google Maps for plumber reviews).

Basically, what I’m saying with all of this is the “focused internet company beats large internet company trying to enter space” argument. Yelp is focused on discovering local businesses, and it’s tough (but not impossible) to see competitors with different app interfaces and user needs moving into Yelp’s space.

Yelp is obviously dependent on the big tech phone platforms (i.e. Android and Apple) for getting their product out. Some type of push from the tech companies to take a bigger cut from apps in general or push users from Yelp to another product would hit Yelp. I’m not sure exactly how this would work (or how this would go further than Google’s push today to get people using their apps on Android), but it’s obviously a risk.

I’d guess that Yelp is too small for the tech companies to target specifically, and if they did something sweeping to try to take more of a cut from all apps they'd probably face some type of regulatory pushback.

Related to tech platform risk: Yelp’s Apple partnership ends. Yelp is the default review site when you look a place up on Apple maps. I haven’t seen any statistics on how much of Yelp’s business / reviews come from this partnership (I can’t imagine it’s high given I’m not sure how many people actually use Apple maps and I don’t believe I’ve seen it disclosed in any filings or talked about anywhere), but I suppose there’s a risk this ends

I wonder who Apple would switch to if they tried to go off Yelp. Tough to imagine them turning to Google or Facebook for review services. They could do some combo of Tripadvisor and Opentable, though it seems like the review set between the two of them would leave off some categories (mainly home improvement types), or Apple could try to internalize the review function. Ultimately not sure if it’s a game changer for either side if Yelp is on Apple Maps (or if reviews are on maps in general).

Yelp is also the default review site for Bing maps, though again I’m not sure how much the partnership matters.

Regulatory crackdown of some form. Probably a silly thing to worry about as Yelp is likely too small to be on regulators’ radar (seems like Facebook and Google would be top priorities), but I can’t help but read this article on how TripAdvisor changed travel and is struggling with some of the repercussions and think that Yelp could be vulnerable to some of those issues.

It seems like courts aren’t holding Yelp libel for reviews, so maybe this is a bit too draconian a worry.

Bad debt expense- Yelp increased bad debt expense in Q3 and blamed the increase in new accounts. That makes plenty of sense to me, but p. 36 of their Q3’18 10-Q calls out a $25m increase in accounts receivable due to customers paying in-arrears. It’s possible we see more A/R write offs in the near future, though it’s likely the write-offs wouldn’t be large enough to really move the needle.