Some things and ideas: March 2019

Some random thoughts on articles that caught my attention in the last month. Note that I try to write notes on articles immediately after reading them, so there can be a little overlap in themes if an article grabs my attention early in the month and is similar to an article that I like later in the month. Podcast and interviews

The Rangeley Team did a podcast where we talk about some of the ideas and links on this post. You can find the podcast at that link or on iTunes (I'll work on getting it on Spotify and a few other podcast players in the near future).

If the reception is good, our aim is to do a similar podcast once a month in advance of posting the monthly links. Feedback welcome!

Also, Chris and I did an interview with Hedgeye; you can see it here if you're interested.

Monthly value theory ponderings: should we be sitting on our hands more?

As an investor, the most dangerous time to get news is Friday afternoon (particularly after 4:30). If a company you own publishes news after market close Friday, it's almost guaranteed to be bad news, and it's often going to be disastrous news. Case in point: last Friday afternoon, Recro Pharma (REPH; disclosure: long a small tracking position) disclosed they got a complete response letter for their major drug, IV Meloxicam. Obviously, this was a disaster for the company, and the stock responded in kind on Monday, dropping ~35%.

I had previously done some work on REPH, so of course the 35% stock drop drew my eye. As I was brushing up on the company I found myself with a little extra pep in my proverbial step.... looking at a company when it seems the current shareholder base is panicking is a lot more fun than being on the other side of the trade!

That experience got me thinking.... are we all simply doing too much? Would we be better off just sitting on our hands, building up a watch list of companies, and holding cash until periods of true dislocation, whether they be at the individual company level (as potentially could be happening at REPH during a draw down that extreme) or at the market level (i.e. during Q4 last year, one of the worst quarters in recent market memory)?

I'll admit this isn't exactly a ground breaking theory; it's basically "buy when there's blood in the streets".

Only buying in a panic is an interesting thought / theory, but I'm not sure how practical it is for a few reasons.

From a professional standpoint, it's very difficult to avoid doing anything. Whether you're a fund manager communicating to outside investors or an analyst talking to your portfolio manager, the line between "sitting on your hands waiting for a panic" and "being lazy and watching a lot of netflix" is pretty hazy to the people who are counting on you to generate ideas and make solid returns.

From an expected value standpoint, if you really come to know and understand a company / stock and think it's worth $100 and it currently trade for $50, aren't you really hurting yourself by not buying it immediately simply because you're waiting on a "panic"?

From a human psychology standpoint, my guess is that if you're holding 100% cash and a true panic comes, it's going to be difficult to deploy it. For many people it might be because they're too scared to buy in a real panic.... but I wouldn't be surprised if many of the people who are actually able to just sit on their hands and wait for a good panic would find themselves unable to deploy their cash because they keep waiting for things to get even worse.

Or, what if you become a man who sees a panic in every big stock drop? If you limit yourself to only investing in panics, couldn't you see yourself looking at a company that reports bad news and sees its stock cut in half and convincing yourself it's a "panic" when it's really just the market properly adjusting to bad news?

Somewhat relatedly, if you'll only buy a panic, aren't you likely to under estimate good news? One of the most "advanced" skills I think really good investors have is being able to increase their positions when their thesis in a stock is playing out and the stock has done well but not as well as the fundamentals suggest (i.e. when I bought this at $10, I thought this was worth $20; today it trades for $20 but I think it's worth $100 so I'm going to buy more); if you're limiting youself to only buying in a panic, then you've completely removed that "add as intrinsic value increases" move from your toolkit.

Again, none of these thoughts are new or original (one of the challenges of investing is that there really aren't any new thoughts; there are really only new applications of old thoughts / theories). But it's something I'm spending more time thinking about: how do you balance being able to buy when there's blood on the streets (i.e. having cash to deploy in a panic, whether it's a name you currently own or a name you've been following) with the opportunity cost of not being fully invested in your best ideas and the risk of missing out on good ideas simply because you're waiting on them to fall further?

The Problem for Small-Town Banks: People Want High-Tech Services

An interesting look at some of the problems that smaller banks are running into. I enjoyed the article, but I thought it was rather biased in favor of small banks in several ways. For example, one paragraph notes that staffers who transferred from BoA to NBDC when NBDC bought some BoA branches were happy at first because "NBDC was less focused on sales." Hey, that's great for employee moral, and obviously there's a limit to how hard you can focus on sales with a bank (Hello, Wells Fargo!), but if NBDC is buying branches and pushing employees to sell less, of course that's going to be a problem!

Examples like that dot the article. The title of the article focuses on people wanting high-tech services, but in many ways the article is about NBDC botching a merger integration.

I do think the "can small banks afford high-tech" argument is interesting. If the answer is no, then that's an argument for continued consolidation and for the larger banks to have a huge scale advantage, and as a casual banking observer it seems the last few years has born that out. But I think there's something of a counter argument to that: it's easier than ever to outsource tech today. McDonald's has incredible scale, but whenever I go to a new burger place they have point of sale and other technology that seems reasonably comparable to McD. It seems like it shouldn't be crazy had for banks to outsource / purchase a lot of this tech.

Of course, this is the financial sector, and there's crazy amounts of regulation, which might make it a bit harder to outsource the tech / keep up with the big banks than in a less regulated industry like restaurants. Still, it seems like the barriers to having good tech should have gone down now that things like AWS have made servers and processing power widely available without needing to invest in mammoth private data centers.

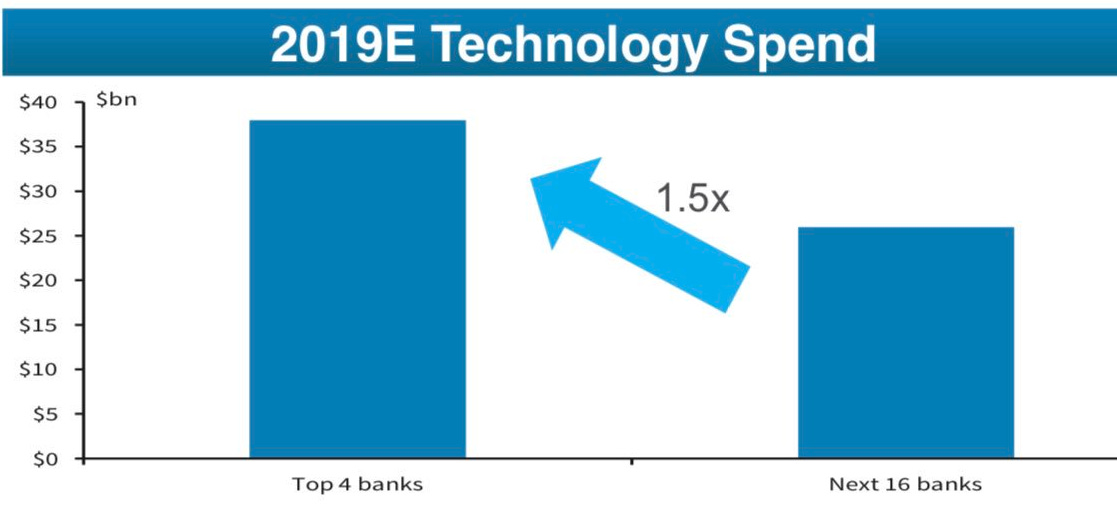

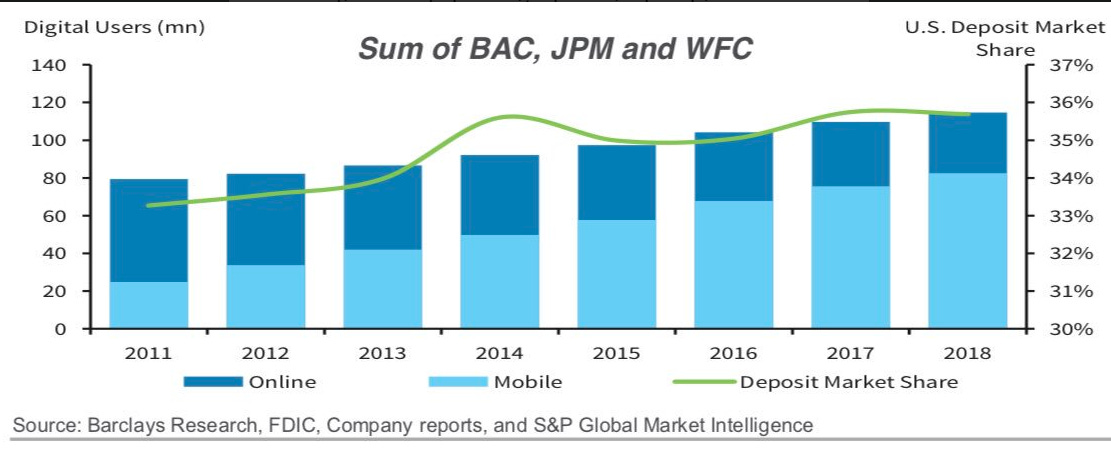

The slides below, from this tweet, show the degree of tech spend "edge" the largest banks have over their (slightly smaller) peers and how they have continued to take share over the past few years.

Some follow up on my KKR write up

There were lots of feedback / questions from my KKR. A few of the most frequent

"The IRR number PE funds provide is BS; you can't compare them to index funds." I'm with you; the IRR number probably paints private equity in too favorable a light. But just because you think the number that private equity likes to float for their fund returns is too aggressive doesn't defeat the rest of the argument (KKR is too cheap, the alternatives will continue to gain share of wallet, etc.). The share of wallet piece is especially important: alts have been around for decades. Large LPs clearly see some value in them as they continue to invest in them (and are generally increasing their investment); I guarantee you they know about the IRR argument but they are "voting with their wallet" and continuing to invest in these funds. (See, for example, "Calpers wants to double down on private equity," which includes the astonishing quote "We need private equity, we need more of it, and we need it now". See also "The Dilemma Facing a $358B Investing Giant")

"You're valuing book at book value, but this is a 'conglomorate' and it should trade at a much wider discount to book." I think KKR's book gets you fee advantaged access to KKR's funds, and I like that exposure. I think their funds will do at least as well as the general markets going forward (whether that's due to alpha or just levered beta is a different question). I'm fine valuing it at book (I wouldn't be surprised if we look back ten years from now and their results show we should've valued it at >book value), but if you want to value it at a discount, that's what makes a market!

"The fee related earnings (FRE) number KKR and its peers touts are BS". Again, I understand this view. KKR's fee related earnings number is particularly suspect as they just assume a margin to get to their number (check their disclosures), but across the board alternative asset managers FRE numbers are pretty inflated (for example, they ignore stock comp, which is a major number). I think the issue this runs into is a lot of the stock comp and other expenses are associated with bonuses / carry pool, which are probably more properly assigned to the incentive fee stream. I think the multiples I used were more the conservative enough to account for the stock comp and other things (if you allocate the stock comp across the business and then apply a multiple, you see that it doesn't move the valuation too much).

Bruce Flatt (CEO of Brookfield / BAM; disclosure: long) did some interviews (including two in Australia, Brookfield's $20B bet against repid Revolution and Brookfield unlikely to fight Aussie super funds for mega deal and a long one on BB w/ Howard Marks) in the wake of his deal to buy Oaktree; I just wanted to pull some quotes because I thought they were important to highlighted pieces of the alternative asset manager thesis so well. Obviously he's "pitching" his own company / goods, but that doesn't make what he's saying wrong!

On Oaktree's management staying around after the deal: " 'They're going to be major owners beside us,' Mr Flatt said. 'These businesses are all about people and we are going to have them for a long time running this business." Mr Flatt said the deal was an example of the way funds management was becoming super-sized, both in the size of the deals and the size of the clients.' "

On LPs looking to write bigger checks with fewer managers, " 'What's happening in the investment world, but also in the alternatives world, is that institutions are getting bigger, and what that means is they need to place larger sums of money. And to be able to do that they need large managers and they want multiple products with those people.' "

On LPs increasing allocations to alternatives, "But Mr Flatt said alternative assets would become an increasingly important part of the asset holdings of super funds, predicting '"most institutions will have 50 per cent alternatives 25 years from now' ".

More on BAM / OAK: Oaktree could be winner in BAM acquisition; Understanding BAM / OAK $500B colossus; BAM's 2018 AR (and a quote on how size is a competitive advantage)

Sports media update: A core tenant of the monthly update: continued highlights of the increasing value of sports rights (mainly because of my love of MSG (disclosure: Long)).

How much are the Cubs worth? Try $2.175B

While >$2B is a big number, it's less than the most recent Forbes "appraisal" of $2.9B. As an owner of the Atlanta Braves through BATRA (disclosure: long), does selling a stake at a decent discount to the last Forbes number (which is what investors generally anchor on when doing an SOTP for equity valuation) a worry? Not really. Would I have rather the stake sold for $4B to make the "these things go for a premium to Forbes" story a lot easier / more comfortable! Sure. But the Cubs stake sale was a 5% stake that was sold to the majority / controlling shareholder. The real value from being a team owner comes from soft power: influence, fame, etc. A 5% owner doesn't really get any of that, particularly if the 5% owner is a corporation (i.e. not an individual). Those dynamics present a tough selling market for a minority stake seller; the best buyer is probably the majority owner and they have a ton of power to drive a very hard bargain.

NFL, Networks Mull Sunday-Afternoon Shake-Up for TV Football

EA reportedly paid Ninja $1m to stream Apex Legends (on Twitch)

OKC jersey patch deal completes sponsorship for all 30 teams

EBIX's strange offer for Yatra

(Note that I wrote all of this on March 11th, right after the EBIX / YTRA offer came out. To the extent anything new comes out between that date and posting, I will add an update at end).

EBIX made an offer to buy Yatra (YTRA) earlier this month. I try to follow the event space pretty closely, and I don't think I've ever seen an offer as strange as this offer. Consider:

EBIX offered cash or shares at EBIX's election. Normally, the target (YTRA in this case), not the buyer, would get to chose between cash or shares. Still, as this is a preliminary offer, this part isn't too crazy; perhaps EBIX just wanted to preserve optionality for how the structure a final bid.... but that alone makes this somewhat strange! Why would EBIX go public (hostile?) with an offer that didn't have the target's support without having all of their ducks in a row? In general, you go public with a hostile offer when you've been trying to negotiate with the other company and they haven't been responding or have rejected what you think is a solid offer (so you decide to make sure shareholders know an offer was there so they can hold the board accountable / take the offer on their own even if the board doesn't want to). If you're EBIX, why go public with what seems a preliminary offer?

Very related: EBIX has a deal condition in the press release. YTRA must have $25m in cash at close after paying off all of their liabilities. Conditions, particularly minimum cash conditions, are generally the result of a negotiation. Strange for EBIX to be so upfront about such a specific condition.

From there, things get stranger. EBIX says YTRA must eliminate their outstanding warrants before close, otherwise EBIX will go out and buy the warrants and adjust the offer downward by whatever it costs to buy the warrants. YTRA's warrants are priced at $11.50/share; it seems strange to have cancelling them be a condition to the merger (if you're making the offer in cash, they're worthless. If you're making the offer in EBIX stock, they'd stay outstanding but they could be dealt with at minimal cost later).

If EBIX decides to offer shares, they'll have a minimum collar value of $59. These are pretty common and designed to protect EBIX from diluting themselves too much if their stock drops too far (for example, AT&T had a collar in their Time-Warner deal). But EBIX was trading for ~$50/share when the offer announcement came out; it's pretty strange to structure a floor that's (well) above where your stock is currently trading!

Everything above is strange. But the strangest part is EBIX offers YTRA shareholders "downside cover" that allows them to sell their stock to EBIX at a 10% discount to wherever the stock is issued. The downside cover is effectively a put option; I can't think of any deal I've seen that involved giving public minority shareholders a long term put. Even ignoring the rest of the offer, why bother offering that? But in combo with the minimum collar, downside cover offer becomes even stranger...

I don't have any real views on the offer. It's really strange, and I'm not sure why anyone thought structuring an offer like this would be a good idea in anyway.... but it seems a particularly bad idea once you factor in this wasn't even a definitive deal!

EBIX has been a relatively popular "battleground" stock (longs / shorts raging about it). That makes the deal structure even stranger: having the strange collar + downside cover along with a minimum cash condition makes it seem like the company is engaging in some strange form of financial engineering to get access to another company's cash.

Other things I liked

Laughing Water issues open letter to Aimia Board (GAPFF; disclosure: long and agree with the letter)

Martin Shkreli Steers His Old Company From Prison- With Contraband Cellphone

Dungeons and Dragons (D&D / DnD) more popular than ever thanks to Twitch

Big media isn't ready to fight back (netflix misunderstanding, Pt. 5)

Verizon faces 'steep climb' to attain attractive return on 5g home

Inside the rise and fall of a multimillion-dollar airbnb scheme

I'm addicted: why Food-Delivery companies want to create superusers

Value Investing in the 21st Century (Interview with Hedgeye)