Some things and ideas: June 2019

Some random thoughts on articles that caught my attention in the last month. Note that I try to write notes on articles immediately after reading them, so there can be a little overlap in themes if an article grabs my attention early in the month and is similar to an article that I like later in the month. Podcast:

You can find this month’s Rangeley Podcast here. On it, we discussed Abbvie's Allergan (disclosure: long AGN) deal, how it was carefully structured to avoid a shareholder vote, and the odds it goes through. Then, we talked T-Mobile / Sprint (disclosure: Short Sprint) as it nears (apparent) DOJ approval, mainly focusing on the unprecedented "flailing firm" defense and opposition from state AGs. We also talked about the odds T-Mobile looks to recut the deal (I'm shocked we haven't heard anything about a recut yet!) and the interesting position Dish has found themselves in as divestiture buyer.

Monthly value theory ponderings: Is the market under-pricing volatility?

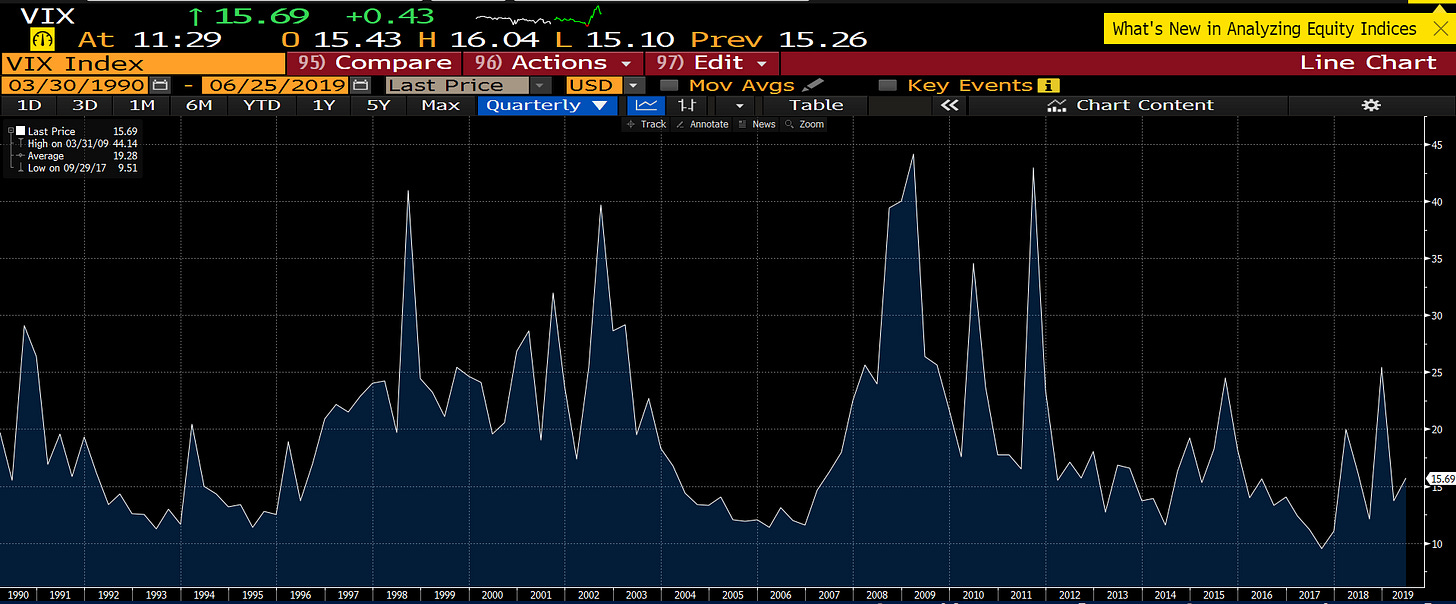

This is a bit more macro / market oriented than I normally think or talk about... but I've wondered recently if the market is underestimating the volatility in the world. I'm not talking specifically about the "Trump is running this country based on his daily whims" factor (though that's certainly a part of it!); I'm specifically wondering if the market is under-pricing volatility currently. I pulled the chart below from Bloomberg; it shows the VIX going back to ~1990. Today's VIX is ~15.7; that's probably a bit below the LT average (the chart says the LT average is 19; I feel like that's a bit skewed up by some higher vol times (i.e. one reading at 100 is going to really pull the average up) but I'm no expert). Anyway, at ~16 the market is basically saying we are in slightly less volatile times than normal.

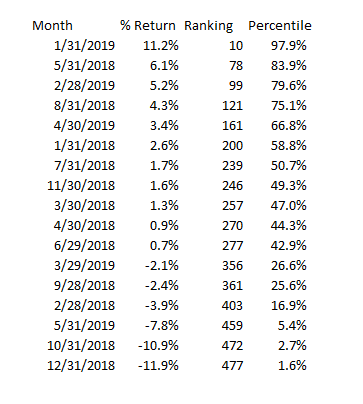

But, despite what the VIX is saying, it certainly doesn't feel that there's no volatility out there. Q4'18 was one of the worst quarters in market history, and Q1'19 was really strong. Below is a table I made that shows the monthly returns for every month in 2018 and YTD 2019 (through May), what the Russell returned, and how that ranks in the Russell's history since 1979. So, for example, the top row is January 2019, where the Russell was up 11.2%, making it the 10th best month of the 485 months since January 1979. That puts it in the 97.9% percentile (10 / 485 months).

So, in the last 17 months (June 2019 isn't over so I haven't included it yet), we've had three months in the bottom ~5% as well as one month in the top ~2% of returns. In other words, four of the past 17 months have been in the "fat tail" portion of the distribution curve (the top or bottom 5%). That seems really volatile, yet the VIX is at or below it's long term average?

I'm sure there are better ways to splice or look at this data (forgive me; I haven't done real statistical analysis in quite sometime!). I think my takeaway is that the real world volatility (trade wars, crazy politics, etc.) is bleeding into the stock market, but that volatility isn't being picked up by the VIX. I would guess there's a trade to be made here (go long out of the money calls and puts), but that's just an observation, not a recommendation!

Companies arbing their capital structure

I mentioned in my 2018 annual letter that stocks looked cheap given they were trading at ~15x forward earnings while interest rates remained low. I've always wondered how long that combination could last: if markets are wide open to lend to businesses at 5-6% and their equities are yielding more than that in terms of free cash flow to equity, at some point someone is going to aggressively take advantage of that combination to make a whole lot of money (buy everything you can at a 15x multiple (7.5% after tax cash yield) with the maximum amount of leverage you can at 5-6% pre-tax interest rates and milk the extra cash flow). Over the past ~five years, I think we've already seen the beginnings of "bid it up because debt is super cheap" in a lot of stable infrastructure projects and some trophy real estate properties, where long term money (insurance / pension money) has bid the equity on those projects down to low single digit cap rates.

I don't have any statistics on this, but I wonder if this thinking is starting to bleed into the equity markets / if companies are finally getting more aggressive in taking advantage of this. I say this because I've seen a crazy amount of companies raise long term debt at really low rates in the past couple of weeks. As an example, I'll just pull my favorite company, Charter (disclosure: long through Liberty). This week, Charter raised ~$2B in notes ($1.25B in ~30 year paper and $750m in 10 year paper) at interest rates slightly above 5%. Yes, some of that will go to refinancing some debt that's about to mature, but some will also go to repurchasing shares. With their equity trading for <20x this year's FCF and with FCF growing, they are effectively borrowing at 5% to buy their equity at >5%. Eventually, that gets really accrettive. Again, this is nothing new; it's been happening for years, but I feel like I've seen an acceleration in it across companies in the past week and if it turns out companies are getting really serious about pushing debt levels higher to repurchase shares I would guess there's going to be a ton of really happy equity investors.

It's entirely possible that I'm looking at this on a biased sample. The companies I follow are significantly more likely than the average company to utilize leverage (particularly for share repurchases); however, I feel like I've seen this across a broad sample of companies.

I feel like a backup to aggressive share repurchases is M&A, and it doesn't strike me as a coincidence that we've seen so many mega-merger deals this month as debt markets have been wide open. If you're a conservative mega-cap CEO, maybe an aggressive share repurchase plan isn't in your nature (or your board's nature, or politically feasible).... but maybe taking on a bunch of cheap debt to buy a competitor at a free cash flow yield in excess of what your debt costs plus realize some synergies plus run a bigger company so you can justify a bigger salary makes sense?

PS- speaking of companies getting the"trade it to a nose bleed valuation because it's better than a long term bond" treatment, I saw a tweet on Progressive (PGR)'s valuation recently. It's currently trading at 16x earnings and 4x book value. That seems really high for an insurer (regulation, competition, capital requirements, and their size should all preclude too much future profitable growth), but it does raise an eyebrow to think of PGR's valuation and what Geico is carried at on Berkshire's books...

Sports media update: A core tenant of the monthly update: continued highlights of the increasing value of sports rights (mainly because of my love of MSG (disclosure: Long)).

Other things I liked

Boeing built deadly assumptions into 737 Max, blind to a late design change

I can't claim to be an expert on the company or aircraft (though I have been reading all of BA's transcripts and updates on the MAX because I have.... more than a passing interest in the aircraft lessors), but I can't believe that there hasn't been more outrage about the 737 scandal. Wells Fargo fired not one but two CEOs over their fake account scandal; Boeing basically lied to regulators (or, at best, mislead them) and released a faulty product that killed >300 people (and risked tens of thousands more!) and I haven't seen a single call for their CEO to resign in shame? IDK, again I'm not super close to the company so maybe I'm just blaming the CEO / company for a problem that was too large for any one person to catch, but it still seems like this should be a way bigger scandal than it's currently playing out as.

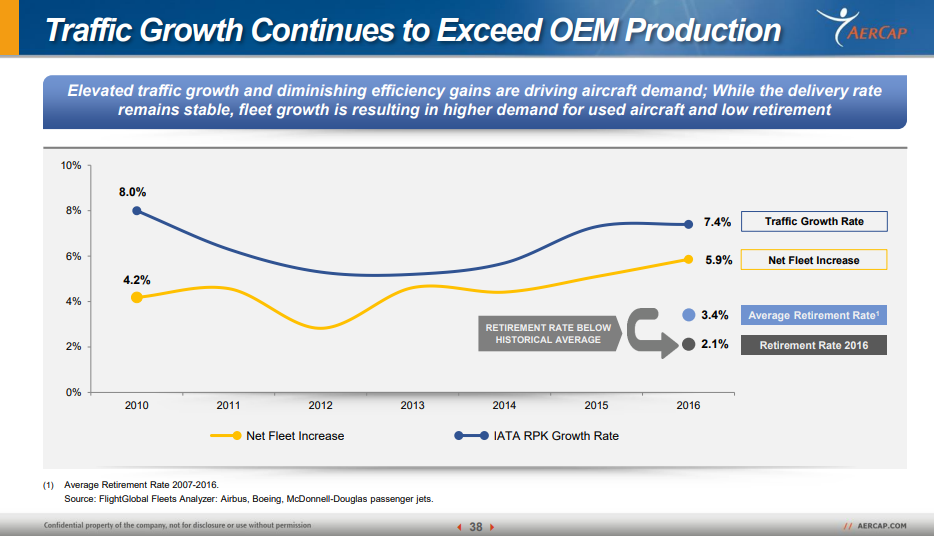

Speaking of aircraft lessors, a question I've been struggling with recently: given the issues with delivering new aircraft (Boeing's Max problems have caused it to drop from 52 new planes a month to 42, and obviously none of those are currently getting delivered, and Airbus has struggled with deliveries as well), is it possible we're going to see a mini-aircraft shortage in the next few years / used aircraft pricing is going to be materially stronger? The aircraft lessors trade well below book value and have a history for selling their used / midlife aircraft at a slight premium to book; is it possible they start selling airplanes formore than a slight premium in the future?

Maybe Boeing dropping from 52 planes to 42 planes a month seems small. But that's ~120 planes/year, and (if you believe Air Lease) aircraft demand is going to double over the next 20 years while ~75% of the aircraft fleet is going to need replacing, including >600 planes/year over the next five years. Boeing cancelling 120 planes/year represents 20% of the planes needed just to replace those age outs! If you're an airline that's retiring a plane and suddenly Boeing has had to push out your plane delivery by two years because of this issue, you can either cancel a route (and lose a ton of revenue), or you can go buy a used plane. Put that math across 100 different airlines and suddenly you could see much stronger demand and pricing for used planes.

Just to drive the point above home a bit further; the chart below is from AER's (disclosure: long) 2017 investor day. It shows that air traffic growth has continued to exceed the increase in the air fleet, and that the retirement rate for planes has been below historical averages. What happens to aircraft pricing if the "net fleet increase" comes down (as I think it should given the aircraft production issues) while traffic growth continues to increase? What if the retirement rate increases too?

To be clear, I'm not suggesting used plane pricing is going to go through the roof or anything. But the airline lessors are heavily levered and generally trade well below book value; any increase in residual value of their planes has a big impact on the stock. For example, Air Lease (AL) has ~$16.2B in net book value of planes and ~$5.2B of equity value. If their planes were suddenly worth just 1% more on the open market, that would be ~$1.50/share in increased private market value. That's a pretty solid bump for a stock that trades <$39 as I write this (June 9th).

I'm still thinking this through, and there are some clear risks to that "increased book value analysis" (for one, almost all of the air lessors' planes are on long term leases, so they couldn't exactly be sold off today, and even if they could trying to mass liquidate all of an air lessors planes like that would probably crush prices). Still, it's an interesting thought; I'd be interested if someone deeper into the space than me had thoughts on it!

Fiat's Elkann keeps family support in wake of busted merger (look at some of the family dynamics behind EXOR, which I am long)

Choosing the wrong lane in the race to 5G (opinion piece from an FCC commissioner arguing we need more focus on midband, not millimeter wave, for 5G rollout)

Why Amazon is going to be one of the winners of the streaming video wars (podcast with Peter Kafka and Matthew Ball; worth a listen / read)

The couple who feds say scammed Berkshire Hathaway for millions

a16z on the podcast ecosystem (lots of interesting stuff on apple and spotify market share)

Nick strikes Ryan Toysreview international merchandise deal amid bet on social media influencers

ARK Invest's effective Tesla model (disclosure: short TSLA)

How did WeWork build a $47B company? Not by sharing

So many great things in there, but here was my favorite

The days of getting a cheaper cable bill by threatening to leave may be over

As esports grow experts fear a bubble

Lots of interesting stories and stats in that article. I think it's a bit too negative; of course a ton of investment into nascent e-sports field isn't going to work, but one or two of them will work (that's a guarantee, given the popularity), and the ones that do work will be mega-grand slams.

Another thing to remember: it's possible for a league to be successful even if it's operating at a pretty big loss because it creates value elsewhere. Ferrari loses >$100m/year on their F1 team. That's an enormous expense, but I would guess it's worth it for them: a lot of the R&D for the F1 team probably helps with their "regular" cars, and the marketing for the Ferari brand is unreal (backing up that the expense is worth it: both Ferrari and Mercedes threatened to quit F1 when Liberty proposed putting a cap on their spending to make the league more even). Something like Overwatch may not work out for the teams themselves (though it might!!!!), but if Activision can get the Overwatch league to be super successful and it drives more users to the game, the league could be burning millions of dollars and it could still be incredibly successful for Activision (to be fair, the article touches on this point a little towards the end, but I think it understates it).

Hamilton $849 ticket a bargain? (disclosure: I saw Hamilton this week; it was incredible and fortunately wasn't $849/ticket.)

Debt, Conflict and Vacancy Imperil Kushners' Times Square Dream

Abercrombie & Fitch closing down flagship stores to boost profits. (related: Manhattan's Newest Flagship Department Stores are Ignoring the Retail Apocalypse):

I'm long physical retail in a few different forms (mainly BPR, and mainly BPR through BAM (long both)) with an underlying thesis that 1) class A malls are in great locations, which gives them significant downside protection from redeveloping even if physical retail is going to zero and 2) online players are increasingly releasing that having physical store presence helps their online sales (for example, in my October links I linked to this piece on Warby Parker heading to malls), so this article obviously caught my eye a bit and made me wonder if the second piece of that thesis (physical stores boost overall sales) was getting called into question. Alternatively, it made me wonder if legacy physical brands didn't see the same overall / online sales boost from having physical stores for some reason (perhaps A&F didn't get an overall boost because they sprayed so much perfume in their stores customers couldn't see their phone screens through the fog?) or if legacy retailers did see some boost from having a physical store but weren't as sophisticated in tracking boosts to online sales. All of those assumptions proved wrong though; it seems A&F is seeing a boost from their physical stores, the flagship stores just probed too expensive to continue operating (see the quote below from their Q1'19 call). That is kind of interesting though; I wonder if it's a failure of imagination. Malls are increasingly looking to bring in experiences (escape rooms, gyms, more food courts, etc.), and I wonder if legacy retailers could make flagship stores work better by making the stores more about experiences. Not sure how that would work with A&F, but someone like Nike could turn their flagship stores into part gym / part retail space, or a golf retailer could have a VR Top Golf experience. There are tons of other options I'm sure I'm not thinking of, but I do wonder if flagship stores failing is more failure of imagination than failure of the retail space.