Should the airplane lessors be flying higher? $AER $AL

I mentioned the aircraft lessors in my June links post, and as I was writing the post I decided I wanted to do a fuller write up on the lessors because I thought I had a few non-consensus views on them and, in particular, on their risks (in addition, I think the discussion of Buffett's thoughts on lessors and how its tough to reconcile it with his investment in airlines was different). My general thesis on the lessors is pretty simple: they trade at a discount to book, and they probably deserve to trade at a premium, both because their book value is understated and because they have some franchise / platform value. With continued earnings growth driving by new plane deliveries into long term contracts with airlines combined with share repurchases below book value, I could see the shares delivering 20%+ IRRs for the next three years. The two major public players are AerCap (AER; disclosure: long) and Air Lease (AL); Aircastle (AYR) and Fly Leasing (FLY) are also publicly traded. While I've read through most of ARY / FLY's transcripts and financials, I've spent much less time on them than AER and AL so this post will mainly be AER / AL focused. There's plenty of information out there on the aircraft lessors.David Einhorn pitched Aercap in both 2015 and 2019 , and if you google around you can find lots of info on his thesis (the 2015 pitch at Grants included detailed slides; I'm sure you can find them if you google around but I can't find an easy link to share here. Valueandopportunity had a nice summary of the Einhorn pitch back in 2015 (part 1 and part 2)). The stock has also been written up 5x on VIC and plenty of times on other finance sites. Given how much info is out there, I'm only going to touch very briefly on the basics of the business; I'd encourage you to go hit all of those resources for more (or you can just see the quote below from AER's Q3'18 earnings call, which sums up the investment thesis pretty nicely).

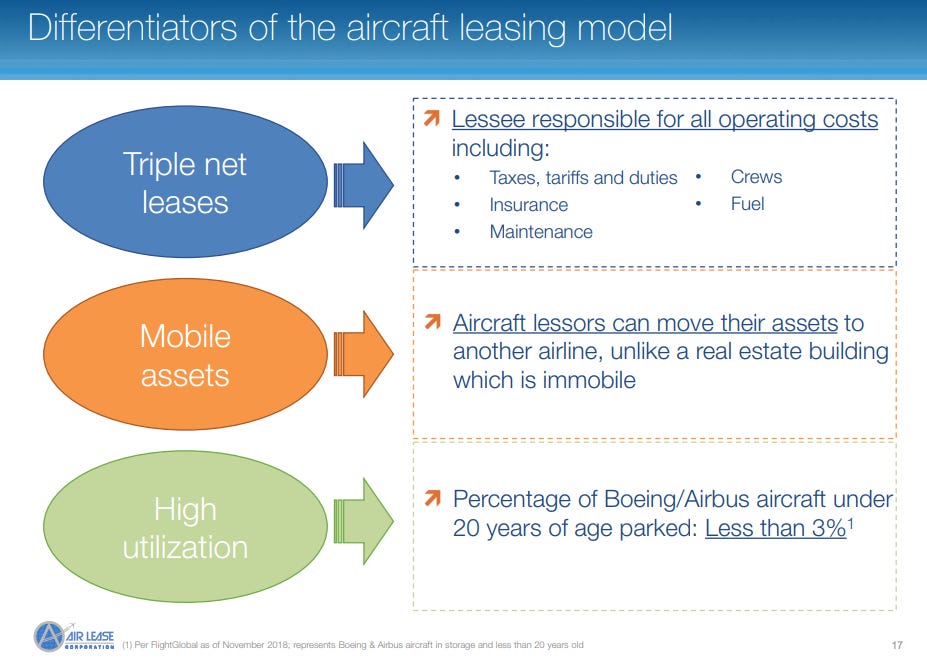

At its core, an aircraft lessor is a pretty simple business. They buy airplanes and then lease the planes to airlines. The leases are generally triple net style leases, where the airline is responsible for all expenses, including operating expenses, taxes, maintenance, etc. The leasing model is pretty ubiquitous across business (landlords lease buildings to tenants, car companies lease cars to consumers, etc.), so we're not exactly dealing with an unproven business model. However, the aircraft leasing business is a bit unique because there aren't many commercial aircraft models out there and aircraft are highly mobile. Given that combo, a good airline lessor can quickly repossess and re-lease an aircraft if a lessee gets in trouble. Think of it this way: if you own property and your tenant defaults, you have to go physically kick the tenant out and then try to find someone to replace them. Depending on where your building is located and what it's suited for, that could be easy (for example, if your building is an office building next door to Amazon and Apple in the heart of a major metro city, you can probably find a tenant pretty quickly!) or it could be really difficult (if you're trying to replace a Sears in a super rural class C mall). Aircraft don't have any of those worries: if you leased an aircraft to a struggling emerging market airline and they default, you can just take possession of the aircraft and fly it to a country / airline that's performing better and have the plane generating revenue in no time! (The slide below is from AL's 2017 investor deck; I think it does a nice job highlighting the pros of aircraft leasing).

An obvious question is why an airline would chose to lease a plane versus buy it given the airline is responsible for all operating payments. There are a variety of reasons, but to me the three key reasons are:

Planes cost tens of millions of dollars. Smaller airlines may not have access to enough capital to fund their full fleet; using a lessor allows them to quickly scale up their fleet without accessing huge sums of capital.

Aircraft lessors are among the largest buyers of new planes in the world; this scale gives them some purchasing power with the aircraft manufacturers (Boeing / Airbus) and let's them buy planes cheaper than a small airline could. In addition, aircraft lessors often place orders for new planes when the manufacturer is beginning production; taking this risk and being the anchor customer for a new model gives the lessor advantaged pricing (Air Lease appears to be doing exactly that with Airbus's new planes). Finally, new planes aren't exactly easy to get your hands on; both Boeing and Airbus have a years long backlog. If you want access to a new plane, going through a lessor is probably your best bet unless you can wait several years.

Aircraft last for 25+ years, but many airlines want to fly only newer planes. If you're an airline that wants to fly newer planes, buying planes exposes you to "residual risk" (the risk of what the plane will be worth in when you try to sell it for a newer plane down the line; for example, if you're an airline and you want to run only airplanes less than ten years old, you're going to have to sell every plane you buy today ten years from now and you're going to be very exposed to what people are willing to pay for ten year old aircraft in ten years). By leasing a plane instead of buying it, you stick the lessor with that residual risk.

Historically, aircraft lessors would engage in both sale leasebacks (where they would buy planes from airlines and lease them back to the airlines) and normal aircraft leases (where they buy new planes from aircraft manufacturers and then lease them to airlines); however, an influx of cheap capital has priced the publicly traded lessors out of the sale leaseback market for the most part. Today, the two major publicly traded lessors (AerCap (AER) and Air Lease (AL)) are generally focused on buying brand new planes and leasing them. This is probably the best use of the lessors capital and platform, as the lessors can use their scale to get better pricing from the aircraft manufacturers than most airlines could on their own (The slide below is from AL's 2017 investor deck; it shows that each of the lessors makes up ~13% of the orders for aircraft in 2018. Given how large their order books are, you can see why they can command some pricing concessions).

Ok, hopefully that's a decent enough overview of the lessor business model. Again, if you're looking for more, there's plenty of info out there; I linked to some solid write ups above, and both the Air Lease and AerCap investor pages have lots of info (in particular, I'd recommend flipping through their 2017 investor day presentations (here's Air Lease's and here's AerCap's)). So let's turn to why I'm so interested in the lessors. The largest reason is pretty simple / obvious: valuation. It's tough to argue that the lessors aren't cheap; both trade for mid to high single digit earnings multiples and for less than their book value.

(Note that my numbers may not be purely apples to apples; for example, I'm using adjusted EPS for AL (which excludes stock comp) while using normal EPS for AER. In addition, my numbers might not perfectly match the company's numbers; for example, my book value number is tangible book and I include restricted stock, which results in a bit lower number for AER, and I adjust AL's preferred stock to par value. These are really small differences though; I only highlight to explain my numbers may be slightly different than yours if you're doing a spot check!) The P/E cheapness is nice, but in general I think earnings are a pretty poor way to look at a financial company (which the lessors fall into). The reason is pretty simple: earnings can be really influenced by legacy assets. The easiest way to show this is probably with a bank. Say a bank had made a Warren Buffett style spectacular loan at the height of the financial crisis: something like 12 years at a 15% interest rate. That bank's earnings are going to look spectacular in the near term; however, that loan will expire in the next year or two, and when it does their earnings will fall off drastically as they replace that great distressed loan with normal loans. So I've generally thought the best way to value lessors or any type of finance company is to start with tangible book value (or, if there are some assets on their books that are held above or below fair value, as would be the case in the "Buffett loan" example, fair value those assets and then use that as your starting point) and then assign a premium for any "platform" value the company has (or a discount if the company has negative platform value, sketchy management, etc.), with platform value defined as something that would consistently let them earn returns in excess of their cost of capital. This is generally how I've seen most M&A in the space work: for example, most of the small banks I've seen merge are generally valued at tangible book value plus some premium for their core deposit base. In this case, the deposit base is the bank's "platform value," as core deposits are an incredibly cheap / valuable source of financing that allows a bank to earn higher returns on equity. So my formula for valuing lessors is generally: take their tangible book value, fair value their assets (if possible), and then add a premium or discount for platform value. With both AER and AL trading well below tangible book value, the market seems to be suggesting that both companies have no platform value and that their asset value is overstated on their books. That seems draconian; in fact, I think they have (some) platform value and their assets are actually worth more than they're held on the books for. Let's start by assessing the lessor's asset value. The air lessors currently trade for a discount to book value; assume that the market isn't assigning a discount for any management or corporate governance issues (i.e. some controlled companies trade at large discounts to asset value because the market assumes management will make poor capital allocation decisions or simply take a lot of that value for themselves; both companies' management teams have good track records so I doubt the market is factoring in a management discount) and the only explanation for the discount is that the market does not believe that company's book value represents fair value. Does that make sense? I don't think so. The slide below is from Aercap's Q1'19 earning deck; you can see from the table on the right hand side that the company consistently sells their aircraft at a premium to their accounting figures.

Let's not just trust AER's history of selling planes at a premium; I think using some logic we can make sense of why Aercap's book value would underestimate the value of their planes. Why? Well, first, Aercap's scale probably gets them a bit of a discount when they buy new planes (as mentioned above). Because Aercap can't mark up their planes with a "bargain purchase" when they buy them, the planes probably go onto AER's balance sheet a bit undervalued. An example might show this best. Say that most plane purchasers buy planes for $100/plane. If AER's purchasing power lets them buy the same plane for $97, that's the price they put it on their books for even though they could immediately flip it to someone for $100. Given AER is buying at a slight discount, it makes sense that when they eventually unload these planes they are realizing a gain. Second, AER has argued their depreciation schedule is more conservative than the general industry. I'm not an expert at aircraft accounting so I can't vouch for the accuracy of that statement, but given the consistent fair value gains I wouldn't doubt it. Anyway, the bottom line here is that both some logic and AER's history of selling planes for gains suggests that AER's fair value is likely higher than their accounting values. That's an interesting bottom line. But here's where they story gets more interesting: both AER and AL have a lot of leverage to plane values. AER, for example, has a "net book value of planes" of $35B supported by $8.6B of tangible equity. At their current price of $51, they have a market cap of $7.2B. The difference between their market cap and their tangible book value could be looked at as the market's implied discount on their planes, so at today's prices the market is saying that AER's planes carrying values are ~4% overvalued. I get there was a lot of math in that sentence; the chart below will probably help with understanding that.

Again, AER and AL have a lot of leverage to plane values and have a history of selling planes at a premium to book (in their 2017 investor day, AER mentioned having sold >500 aircraft over the previous 10 years at "consistent gains on sale of between 5% and 10%). The chart below shows the sensitivity for AER and AL's book value per share to changes in the fair value of their planes. For example, the "5%" line shows what would happen if the aircraft were actually worth 5% more than their held on the companies' books; AER's book value would increase by $12.57/share and its fair value would be >$74/share, while AL's book would increase by $7.33/share and its fair value would be ~$52/share (I'm assuming book value = fair value in this example).

I think this chart shows both the appeal and the risk of investing in the aircraft lessors: you are really levered to airplane prices. With AER, we have a ten year history of them selling planes for a 5-10% gain yet their stock trades for a ~5% discount to their plane value. That is not a large gap, but given the leverage here closing that gap just to the low end of the range (i.e. going from -5% of plane value to +5%) would result in a huge gain (>50% share price appreciation). At the same time, you're really levered on the downside. If we run into some type of crisis (whether that's a real financial crisis that cuts into the airline industry / plane values or some type of airline specific crisis that brings air traffic coming to a halt (pandemic, war, loss of faith in air travels due to more crashes or terrorism)), it doesn't take a lot for the shares to be worth materially less than today's share price. How many assets (even hard assets) are there out there that haven't had a 10% drop at some point? Airlines aren't exactly known as the paragon of financial health and stability; if air traffic dipped one year and a wave of airlines went bankrupt, why couldn't aircraft flood the market and AER be staring at 10-15% "mark to market" losses on the cost basis of their planes? Even from today's (I would argue depressed) share prices, moving from a 5% discount to a 15% discount would knock the stocks fair value down to ~$24/share, cutting it in ~half. I'm not saying that's likely or even probably, but obviously there is some significant tail risk here in any scenario where aircraft prices drop even slightly. Still, we have ~a decade of evidence that the lessors can sell planes at a premium to book value, and the market is pricing them at a discount to book value and giving them no value for their "platform" value. That's interesting to me, and it's worth accepting that tail risk to get exposure to that upside (in my mind, the way you solve for an undervalued company with some tail risk is position sizing. Given a small decline in aircraft pricing leads to big equity declines, AER can't be as large of a position as something like MSG (disclosure: long), which has a huge net cash position (so much less leverage) with multiple different stores of value (i.e. even if the Knicks declined in value by 20% (unlikely, I hope, despite Dolan's attempt to ruin the Knicks this offseason!), MSG arena and the Rockettes would still retain their value, and given the lack of leverage MSG's equity value wouldn't move too much on that decline)). Speaking of platform value, everything I've discussed so far has assumed that the lessors get no credit for their platform value (i.e. their ability to earn returns in excess of their cost of capital which would let them trade for more than just the fair value of their assets). Given today's pricing below book value and the probability that book value understates the fair value of the lessor's planes, I don't think you need the companies to have any platform value to justify an investment today. Still, I don't think it's fair to ignore that possibility of some platform value; in fact, I think there's a decent bit of evidence that these companies do have some platform value and they should trade at a slight premium to their asset value. Before I hit their platform value, I want to discuss one other asset that we haven't talked about: the lessors' current contracts / leases with airlines. By valuing the lessors at tangible book, we aren't giving them any value for their in place leases. It's tough to say if the leases have positive value or not (i.e. they could have negative value if they were all done at ridiculously low rates, or positive value if they're all well structured at attractive rates) from an outside view, but my guess is that the leases have positive value both because they're good leases and because the stability and visibility of their cash flows would be impossible for a start up to recreate immediately (AER, for example, has an average remaining lease term of 7.4 years for their leases; that gives them fantastic visibility into their cash flows and their future financing needs). I wasn't sure where to put the value of their leases (should I try to fair value them and value them as an asset? just throw them into the platform value?), but the cash flows from the leases and their length are definitely a part of the thesis (in particular given they provide near term cash flow and downside support) so I figured I'd mention it here before going to platform value. I think the lessors' platform value would come in two places. The first, their ability to use their scale to buy new planes at a discount, has already been discussed so I don't want to dive too far into it. I'll just note that our valuation so far has given them no value for their current order book (we've effectively valued it at whatever they hold it on their balance sheet by valuing them at book value) despite the fact their order books generally have orders for in demand aircraft at good prices and that the lessors scale gives them the opportunity to continue buying aircraft at attractive prices going forward. The second place their platform value would come from is their global scale gives them data / information that only a few other players have. I think AER put it nicely at their 2017 investor day, but rather than just rely on their words I'll try to put my own logic to it. While aircraft buying / selling / leasing is a high dollar value financial transaction, there isn't a ton of public information on it. The major lessors have better information on the market than anyone else in the world because they are buying / selling / leasing planes every day; that gives them a huge edge over a start up trying to edge into the business. That edge might seem small, but imagine you're a small lessor who owns just one aircraft and the airline you leased it to just went bankrupt. What do you do? You're desperately going to be calling up every airline you can think of trying to get your plane leased (remember, these are depreciating assets; every day the plane goes unleased it gets less valuable). Even assuming you find an airline, how do you know what the right rate for the plane is? And how are you going to get the plane from wherever it's currently parked to where the other airline will take delivery? That's a tough job; compare that to one of the major lessors who buys / sells / lease planes every day across the globe. They're probably going to hear word the airline is in distress well before the smaller aircraft lessors do, so they can start lining up new leases before anyone else has a chance. Because they have a global business, they know exactly where aircraft are most in demand and what the current market rate for planes should look like. And they have teams / experience with repossessing aircraft when airlines run into trouble. I'm not saying that the lessors scale is an unassailable moat; however, I do think there size and scale gives them a leg up that should let them earn some extra return on their equity versus a smaller player. So, putting it all together, where should the lessors trade? If you believe that the fair value of their planes is 5-10% above their book value, then the lessors should trade 1.2-1.4x book value before giving them any "platform" value. Maybe throw another 0.1-0.2x premium in their for their platform, and it seems like the lessors should trade for ~1.5x book value. (Side note: at the JPM aviation conference in March, AL's CEO was asked where he thought they should trade, and he said that if you NPV'd their cash flows he thought they should trade at 1.6-1.7x book. I used to think he was being a bit aggressive / a bit of a salesman, but after walking through all of that I can see where he's coming from)

As a spot check, we can look at the ROE's that most of these lessors earn. I took the slide below from ALY's Q1'19 investor deck; it shows they consistently earn an ROE in the low double digits (this is relatively consistent with what the other lessors are getting; I show this slide just to highlight ROE). Above I suggested that the lessors are worth ~1.5x book; if you think they can consistently earn low double digit returns on equity while slightly growing their equity, I would say 1.5x book is somewhere between reasonable and conservative (1.5x book with a ~12% ROE represents a 12.5x earnings multiple, and earnings should be growing accrettively over time given a 12% ROE represents a cost in excess of equity cost).

Let me wrap this up by discussing why I like AER more than AL. I know a lot of investors like AL for their order book of new planes(the largest in the business), the age of their fleet (3.8 years old versus 6.2 years for AER, both as of Q1'19), and their management team (Steven Udvar-Hazy, AL's founder and Executive Chairman, is a legend in the industry. One poster described Udvar-Hazy leaving ILFC for AL as "the equivalent of Buffett retiring from Berkshire and starting another Omaha based holding company, then hiring Munger and his investment team at the new firm to follow the Berkshire model minus the mistakes he identified at Berkshire along the way"). Makes sense to me, and honestly I think both AL and AER will do well from here given their undervaluation and the tailwinds. Still, I like AER more for three reasons:

AER is a bit cheaper, trading at ~80% of book versus AL at 90%.(AER on why they are a bit cheaper than peers).

I like AER's capital allocation better. AL pays a small dividend and doesn't repurchase shares, instead choosing to plow all of their money back into growing their fleet. AER is a consistent large repurchaser of shares. AER seems to weigh all of their capital allocation decisions versus the return they could generate from buying back shares at a discount (views on buybacks), so when their shares trade this cheaply they step up their sales of planes so they can sell planes at a premium to buyback shares at a discount. That's a much friendly form of capital allocation IMO, and I think shareholders will be rewarded from it in the long run.

I get that AL's exec. chair and his team are legendary in the industry, and it's tough to argue with the value they've created. But AER's CEO (Aengus "Gus" Kelly) is no slouch, and at 46 he's young enough that he could run AER for another 20+ years (AL's management team are all in their mid-60s to early 70s).

I don't think Gus gets enough credit for how good he's been. A few weeks ago, I was listening the Invest like the best podcast with Will Thorndike (author of The Outsiders). At some point on the podcast, Thorndike mentioned how one of the things that struck him about Outsider CEOs is how young they were when they became CEO's. Gus became CEO of AER in 2011 in his mid to late 30s. That Thorndike quote on age suddenly made me realize that Gus ticks off a lot of the different boxes for an "Outsider" CEO. Below I've got a chart from the book that shows the difference between outsider CEOs and peer "normal" CEOs;

I'm not saying Gus perfectly meets the definition of an Outsider CEO but I think it's interesting how many of the different boxes he does check off. I think the best example is clearly the focus on maximizing the long term value of the business; relistening to the Thorndike interview it's striking just how focused Thorndike and outsider CEOs are in comparing capex versus alternative uses of cash (repurchases, acquisitions, etc.), and I think it's pretty clear that Gus / AER are focused on the same thing (see this quote from Gus on maximizing long term value of business).

If you listen to the start of the podcast, the first thing Thorndike mentions is how outsiders view capital allocation through the five different avenues. The quote below is from Gus on their Q4'17 call; it almost perfectly mirrors what Thorndike says

Turning away from share repurchases, consider acquisitions. Outsider CEOs are aggressive when they get a fat pitch and willing to make large acquisitions (from the Thorndike podcast around the 27 mins mark "occasional large acquisitions... 30% or more of enterprise value"). Gus became CEO of Aercap in 2011, and right of the bat he was talking a like an outsider. I'd say Gus's first really big move came in 2013, when AER struck a deal ~to buy ILFC from AIG. To buy ILFC, AER gave AIG just under 50% ownership of AER (plus a ton of cash!). It was a truly large swing.... and one of the best deals from a large publicly traded company I've seen. Aer's shares rose by ~33% on the deal announcement and had basically doubled by the time the deal closed in May 2014.

It's worth noting that AER's shares were trading at ~$24/share before the AIG deal. A year before the deal, AER had bought back a huge amount of shares at <$13/share in a block trade from a private equity firm looking to cash out. Repurchasing shares at $13 to issue them a year later at $24 in a deal that sends your stock to $45? That's a true outsider move!

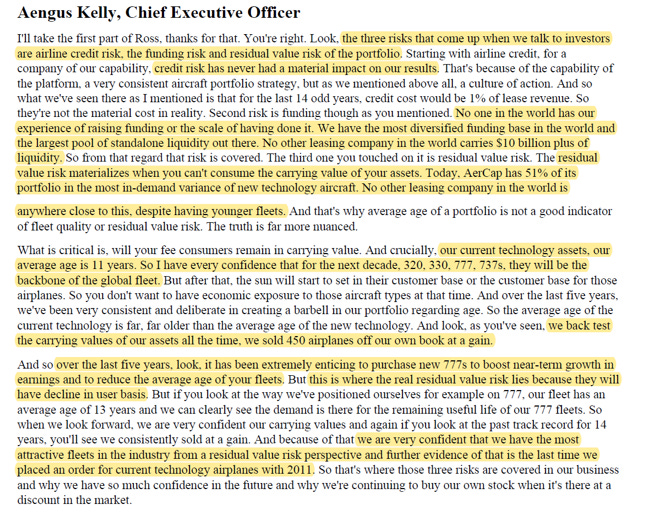

Before wrapping this up, let's quickly turn to the risks for the lessors. The quote below is from AER's Q1'19 earnings call, and I think it does a nice job of highlighting the major risks for lessors.

Of the three, I think the one most people I talk to worry about is funding risk. The lessors has a decent bit of leverage and a lot of purchasing obligations for new planes; investors worry about what happens if credit markets dry up. I'm not crazy concerned about the funding risk: yes, there is some risk here, but both of the lessors have enough cash flow to cover more than a year's worth of obligations, and if they got creative I think they could stretch that a lot further (borrowing against specific planes, asking manufacturers to push out obligations for price concessions, selling old planes for cash, etc.). Obviously none of those are ideal and would probably result in some value destruction, but my point here is they could probably figure out a way to muddle through till credit markets reopened (also, if you're really concerned about credit markets shutting down so hard the investment grade companies with tons of assets can't borrow, there are some really easy and cheap hedges that you can put on that would make multiples of your money to offset this risk if it ever happened!). I also see lots of worries from other investors on credit risk. Again, I'm probably more benign on it than most; I do worry about the type of recession where air traffic goes down and there's a glut of planes so that lessors can't release planes as the airlines are going bankrupt, but given you're buying below book value today I think the market is paying you to take that risk (and, again, there are lots of hedges available if you wanted to go that route). The risk I worry more about the most is residual value risk. Lessors are taking on all the residual value risk for planes, and while so far that's served them well (given they consistently sell for gains), I worry about the potential for some type of shock that crushes the value of planes. For example, in twenty years, if self-driving cars are a thing, does regional air traffic fall off a cliff as more people chose to just drive for any flight that would currently take <2 hours? What about new mandates on fuel effeciency that prove onerous for current models of aircraft (I think about this risk in conjuction with an administration coming in looking to turn America carbon neutral in twenty years or something)? Or China deciding making commercial aircraft is in their national interest and heavily subsidizing a new competitor that can then sell new planes cheaper than older models from other manufacturers? So an investment in Aercap clearly isn't a riskless investment (not that there are any riskless investments), but I tend to think that the risks with a lessor are overblown among potential investors because they're so easy to imagine. It's almost like a person who's scared of flying versus driving. Flying's much safer than driving, but you're scared because your safety is out of your control and an aircraft crash is such a vivid thing. Similarly with airline lessors, I don't think that their risks are any greater than a typical financial company (in fact, in many ways I think they're lower), but I think investors fret about aircraft lessors risks more than a lot of other financial companies because it's so easy to picture them and airline bankruptcies are so ingrained into our minds. Other odds and ends

At Berkshire's 2016 annual meeting, Buffett said he wasn't interested in aircraft leasing in the least. He cited many of the risks mentioned above (residual value, financing risk, etc.). I've had a lot of investors who I mentioned the lessors to say "O, Buffett wouldn't touch it, pass". I get that line of thinking, and honestly I would probably like to be a bit bigger in AER than I am but the "Buffett warned on it" risk keeps screaming in the back of my mind (the man does not warn on much, but his track record on warning on something is pretty good if you exclude his decades long warnings on inflation). Still, at some point as an investor you need to develop your own style and invest in things that don't have the "Buffett seal of approval" or else your "fishing pool" is going to be pretty limited and you'd probably be better off spending your time on something other than investing. I also think it's interesting that Buffett dismissed lessors a few months before he invested in basically all the domestic airlines, as a major portion of the airline's value can effectively be looked at as coming from an internal aircraft lessor. Consider delta: at the end of Q1'19, the company had $29B in net PP&E. Something like 80% of that PP&E was from flight equipment (see p. 62 of their 10-k), so the company has ~$23B in asset value from their aircraft. Delta's EV is ~$50B as I write this; assuming the book value roughly represents fair value from their aircraft, roughly half of Delta's value comes from their internal "aircraft lessor".

I get this might be a bit controversial of a way to look at Delta. "But they can operate their aircraft through a downturn!" Sure, I get that, but it's tough (not impossible, but tough) to come up with a scenario where aircraft values have dropped by 5-10% (the level needed to justify the lessors' current stock prices) but the domestic airline business is going super well. (Airlines also get a huge chunk of earnings from their frequent flier programs (this article estimates ~half of their earnings), which is obviously a super high margin and multiple business, so again... not a perfect comparison!).

Also, Buffett dismissed the airline lessors, but we have no clue on what terms they were offered to him. I'm guessing he was offered ILFC when AIG was trying to offload it (Aercap ultimately bought ILFC in one of the most accrettive deals in recent history; AER's shares nearly doubled on the announcement), but who knows what AIG wanted from him (i.e. maybe they were asking him to assign some value to the order book, and he didn't want to). Maybe this is a bit of a stretch, but I'm just saying the lessors are trading at a discount to book value and ascribing no value to their platforms / order books. Buffett is too large to just buy the stock's on the open market; maybe when people have approached him it hasn't been for a deal as good as the markets are currently offering.

A good way a lessor can get in trouble is buying aircraft "on spec:" putting in an order for a new aircraft without having it already leased to a customer. If aircraft demand remains tight, that's a nice way to make profits (if you're the only person with a new plane available when it's delivered and three airlines are clamoring for a plane, you can get a pretty nice lease rate), but if aircraft demand falls off it's a nice way to get into trouble (either you have to lease the plane at a super low rate just to cover your debt costs, or you have to eat that debt costs for months waiting for lease rates to recover). Fortunately, spec is not a huge concern for the lessors in the near to medium term: AER has >90% of their order book placed for the next few years, and AL has >80%.

As mentioned when I discussed AER versus AL, one of the things that attracts me to AerCap specifically is the combination of super low cost of debt + share repurchases. A few months ago, I got really interested in the local broadcasters (like NXST) and ultimately ended up passing (that turned out to be a mistake!). At the time, the broadcasters could borrow borderline unlimited amounts of money at very low interest rates (like 5%), and many of them were plowing that money into share repurchases when their stocks were yielding ~15% free cash flow to equity. That is a very powerful combo. You can see the broad outlines of that in AER; the debt market is wide open for them to borrow long term at very low interest rates, and they can plow a good chunk of that money back into their shares at well under 10x P/E multiples / well below book value. The comparison isn't perfect; AER has large purchase obligations and their assets are depreciating while broadcasters have basically no capital requirements and their "assets" really shouldn't depreciate (though they do face plenty of tail risks!), but it's an interesting comparison nonetheless.

The repurchases could get really meaningful really quickly. AER repurchased $800m shares in 2018 and >$1B in 2017 and 2016; I don't see why they couldn't approach that amount this year (particularly if they continue to aggressively sell planes). With their market cap <$7B currently, that would let them buy >10% of shares at a large discount to book value, which would be hugely accrettive for remaining shares.

There's been a lot of private equity activity around the space. Apollo raised a $1B aviation fund and tried to buy GE's leasing business, KKR bought 50% of Altavair and gave them a $1b capital commitment (you can find some analysis of that deal here), and Cereberus was invested in AerCap for a long time. Carlyle bought Apollo's aircraft financing business late last yea (you can see their investment thesis here); they also hired an ex-Aercap employee earlier this year. I don't mention this because I expect private equity to buyout Aercap / AL or anything (though I do think they'd probably get a better return from buying AER's stock than from doing this on their own); I simply mention to highlight that some pretty knowledgeable players see something attractive in the space.

Speaking of private equity, Onex (a Canadian private equity firm) agreed to buy Canadian Airline West Jet earlier this year. WestJet's merger docs are interesting; they reveal Onex initially bid $35.75/share for WestJet and pulled their price down to $31/share in the wake of the Max scandal (see ~p.26). WestJet didn't have insane concentration to the MAX (<10% of their current portfolio), though their out-year fleet is pretty MAX heavy (The table below, from West Jet's 2018 AR, shows their current planes and future delivery by type; below that is AER's current plane portfolio (<1% MAX) and order book for comparison); I wonder if Onex was just using the MAX issues as leverage to lower their price or if their DD really suggested that the MAX issues were worth a >10% decrease in West Jet's equity value.

I think I focused a decent bit on the potential downsides to plane values; I think the lessors would argue that's way too bearish. I took the clip below from FLY's Q1'19 earnings call; it summarizes the bull care for owning / leasing aircraft pretty nicely (strong continued global air traffic growth; load factors for airplanes approaching their limits; good airline profitability; low cost of debt for financing aircraft). I agree with this for the most part as a base case, but given the huge leverage to plane values I wanted to have a solid grasp of the downside case and what it takes to get there (which is why I spent so much time focused on it in the article).

A few WSJ articles that highlight some potential negatives / risks