Is $STAR $SAFE? Or is $SAFE a $STAR?

First, and most importantly, this post is about Safehold (SAFE; Disclosure: I am short a small amount of SAFE. Shorting is crazy risky and probably shouldn't be done by anyone. I have openly admitted to having done roughly 100 escape rooms, so certainly consider how ridiculous I am as a source for any type of information) and STAR (disclosure: long a small amount). Second, I am positive that there are some good joke combinations from those two tickers, but the current title was the best I could do (well, the best two I could do). I am very open to improvements. Anyway, on to the post. A few years ago, "yield cos" were all the rage. I mentioned them a bit in my write up on Clearway, but the basics of a yieldco were:

Buy long lived assets that through off a lot of cash, preferably with some type of inflation adjustment up

Use that cash flow stream to promise investors a large and growing dividend (i.e. a 5% dividend yield with visibility into 5% annual growth in the dividend)

In a world starved for yield, investors will bid up that dividend cash stream

Because your stock has been bid up, you can issue equity at really low yields / high multiples, and use that to buy more assets and continue to grow the dividend (i.e. if your stock yields 4%, you can issue equity and buy assets at 10% levered yields and that's crazy accrettive).

Rinse and repeat

That's the simple background, and, of course, the yield co crave eventually ended. I'm just going to steal the CWEN write up on this part for more details; again, I'd encourage you to read the whole piece for more background on yield cos

Let’s start with some background, as it helps think through why this company exists. Clearway used to be NRG Yield where it served as NRG’s Yield Co (it was very uncreatively named). Yield Cos were a popular structure a few years ago. Investors were desperate for dividends, and energy / development companies like NRG had assets like utility scale solar (large solar plants that are plugged into the transmission grid) that had long lives and predictable cash flows through long term PPAs with investment grade utility buyers. The development company could set up a Yield Co that paid out the majority of its cash as a dividend and promised continued rapid dividend growth. Investors would value the company based on their growing dividend stream, creating an extremely low cost of equity capital, which the Yield Co could then use to issue equity and fund more growth projects, thereby continuing to grow the dividend and creating a virtuous cycle of equity raises and dividend growth (a simplified way of explaining it: dividend investors bid the companies way above NAV, so the companies could issue equity at above NAV to fund growth projects and constantly grow the dividend). The model generally looked something like this: Yield Cos would pay out most of their cash as dividends and promise high single digit annual dividend growth. Investors would price their equity at a ~4% yield, and the Yield Co would issue equity at that level to buy energy projects with long term contracts at ~10% levered yields. Rinse and repeat and the company could grow their dividend forever. The energy development company (the Yield Co’s “sponsor”) also benefited: they would get an attractive price for the assets they would sell (“drop down”) into the yield co, they knew they had a buyer waiting in the wings for any project they developed, and they had massive upside from Incentive Distribution Rights (“IDRs”) that let them keep a percentage of any increase in the Yield Co’s dividend/share (p. 148 of TERP’s 2017 10-K has a great example of how IDRs work, so I won’t walk through it here). As happens to all “crazes”, the Yield Co craze eventually ended. The catalyst for Yield Cos falling out of favor was SunEdison’s bankruptcy. SunEdison had been a major sponsor of Yield Cos (sponsoring both TerraForm (TERP) and TerraForm Global)), and its collapse (combined with lower oil and gas prices, which lowered the viability of solar and wind projects that were a major portion of the yield co growth engine, along with a slight rise in interest rates somewhat cooling the dividend growth craze) brought some fear to the sector. Once the Yield Cos stock prices went too low, they could no longer issue equity at prices that would allow for accretive growth and the “virtuous” cycle stopped. Still, as far as crazes go, the Yield Co mania had a fairly decent ending: the assets the company had bought were real and backed by real cash flow, so while investors suffered losses as the dividend growth investors fled and the equity prices collapsed from above NAV to relatively fairly valued (or even undervalued!), the losses weren’t the complete shellackings that generally come with crazes collapsing. TERP, for example, generally traded for ~$35-40/share at the height of the Yield Co craze in early 2015 (while paying ~$1.30/share annual dividend and generating CAFD/share of ~$1.35) and today trades for ~$12.50/share (while paying ~$0.75/share dividend and maybe $0.90/share in annual CAFD (CAFD = Cash Available For Distribution)), and TERP was among the biggest losers in the group from peak to trough.

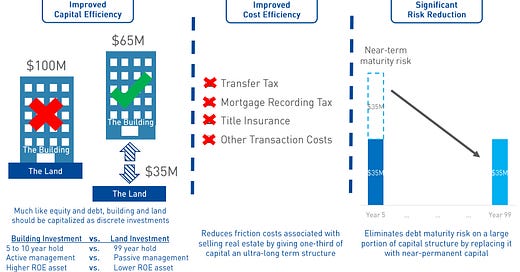

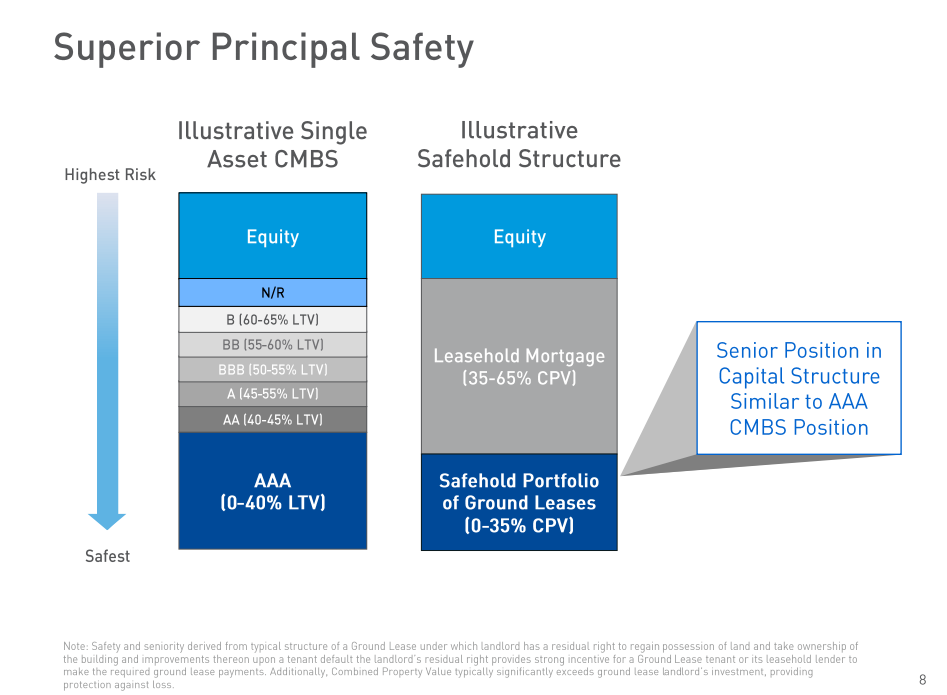

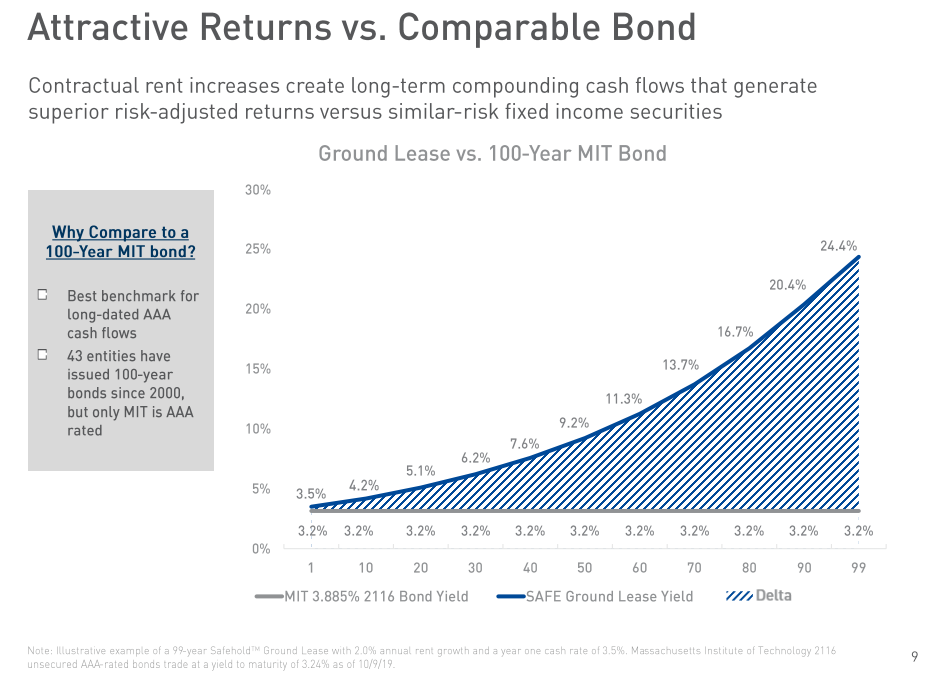

Why do I mention yieldcos? Because I've recently been looking at Safehold, and I can't help but be reminded of the yieldco craze. Safe's basic model is pretty simple: they buy long dated ground leases under commercial real estate. You can see a visual representation of this on the left side of the slide below (from their current investor deck), but I'll walk through it here. Say you're a real estate investor looking to buy a commercial real estate property for $100m. You're probably looking for double digit IRRs on your investment. SAFE argues that owning the actual land underneath the real estate is ineffecient for you as an value add commercial real estate investor seeking double digit returns; the land is a low risk asset that requires no asset management.

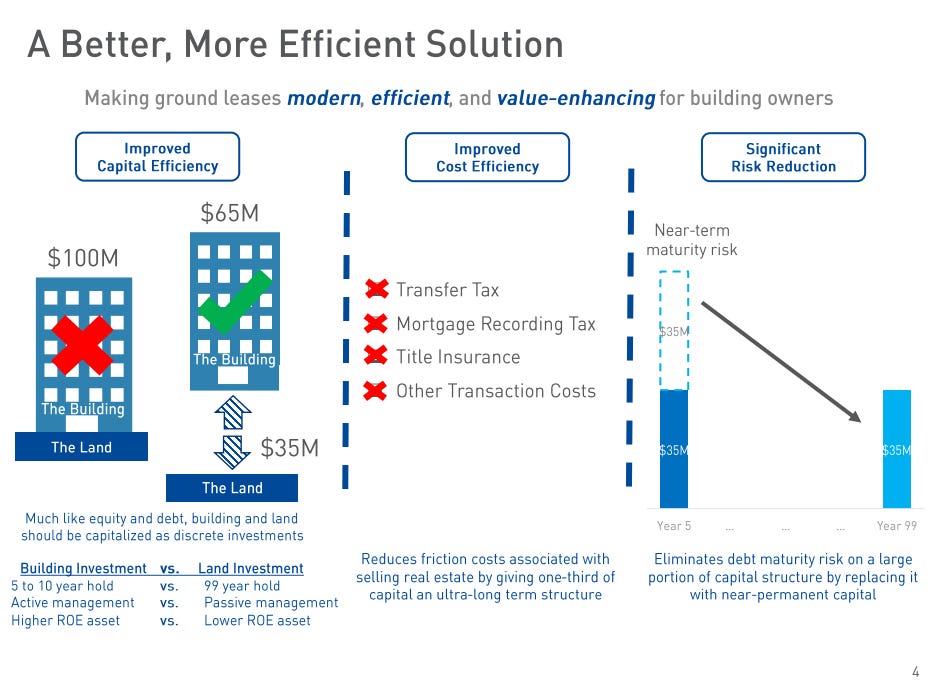

Safe will buy that land from you (the commercial real estate investor) at a very low cap rate, which allows you to reduce the amount of equity you need to put into the building and juice your IRR.

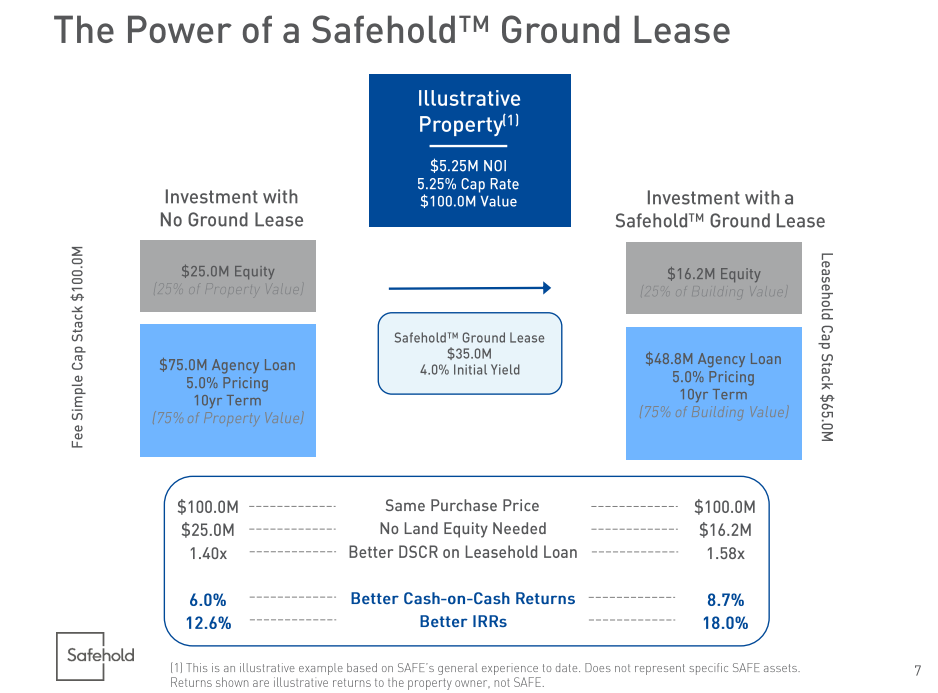

SAFE pitches this deal as an all around win. The commercial real estate investor juices their IRR and writes a smaller equity check. SAFE gets an attractive long term lease, and Safe's shareholders benefit from exposure to an asset that SAFE believes is equivalent in safety to a AAA security but with better yields and longer term upside.

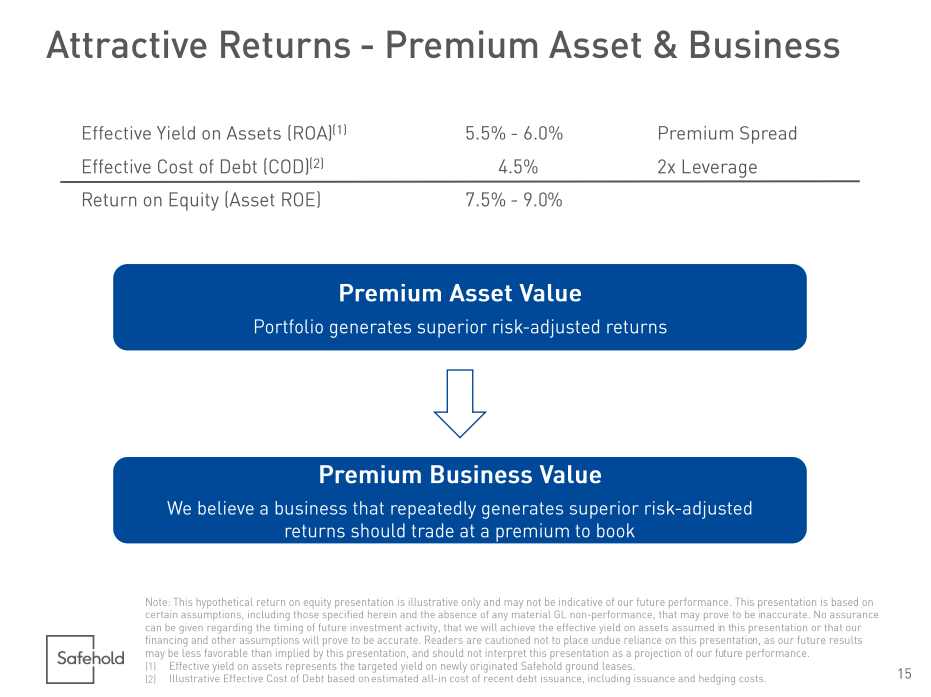

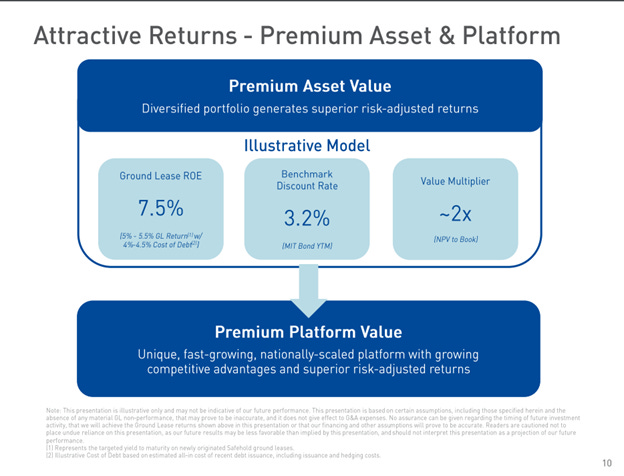

An important piece of the deal to note is that, at the end of the ground lease, SAFE will take ownership of the building. This provides SAFE a very long dated call option on the building. SAFE thinks that they can generate high single digit ROEs through this model. Basically, they'll buy land at cap rates of ~4%. Rent will increase ~2%/year, and the building's value will similarly increase by ~2% year. This will result in a long term return on the asset of ~6%. Apply 2x leverage to that, and the underlying return on equity comes out ~high single digits (see chart below).

SAFE thinks that's an incredibly attractive business model, and they're not shy about letting people know about in. In fact, they think the returns are so strong that every deal they do is instantly worth double its value (i.e. if they buy a building for $100m under this model, the NPV of that deal is $200m, so they've effectively instantly doubled their money).

Alright, that's basically the company's pitch, and I do I think there's a lot to like in there! However, I've currently got a small short position in the stock for three reasons, all of which are somewhat related.

SAFE is providing ground leases to extremely sophisticated commercial real estate investors. Those investors are only going to take SAFE's money if it's the lowest cost of capital they can find (i.e. they're going to look at what SAFE's offering, and then compare what SAFE's deal looks like for their economics versus simply buying the whole thing and taking the largest mortgage they can get). That comparison subjects SAFE to something of a winners curse: every ground lease they win they will have won because they offered the most generous terms.

Let's go back to the $100m deal SAFE pitched earlier. In it, SAFE provided a $35m ground lease, which reduces the investors overall check and juiced their IRR. I have two issues with that illustration: first, it assumes that a lender is going to give them the same terms on the first mortgage (a $75m mortgage for the whole property) and the second mortgage (a $48.8m mortgage for just the building). Lenders are sophisticated; I feel pretty confident they are going to look at the second mortgage as more risky and increase pricing (or reduce LTV) accordingly). Second, it assumes that the investor takes SAFE's deal. If SAFE's deals are really so profitable that they are instantly worth twice what SAFE pays for them, the investor can figure that out, and they're going to negotiate SAFE's rate down or they'll find a competitor who will bid more generous terms.

At its core, SAFE's ground leases are simple financial engineering; it's cleverly structured financial engineering, but it's financial engineering nonetheless. There's nothing wrong with financial engineering (I actually think it's really positive when done right), but there's really not a secret sauce to financial engineering. Despite what SAFE says, I don't see any moat or advantage in being a financial engineering providers.

SAFE's argument is they are currently the only people offering ground leases in this unique structure. Maybe that's true, but I don't see anything unique about the structure that can't be copied by a bunch of competitors.

I'll just simplify it in this point: SAFE is offering a product that is, at its core, simple financial engineering. I see no way that SAFE can offer a product that can be pretty easily replicated and continue to create the huge amount of value they say they are creating. And I really doubt commercial real estate investors are in the business of giving SAFE that long term call option on the building for free; I'm sure they're pricign it out and ensurign the safe ground lease is, all in, more cost effective than taking a mortgage out on the full building.

The incentives around SAFE are simply awful.

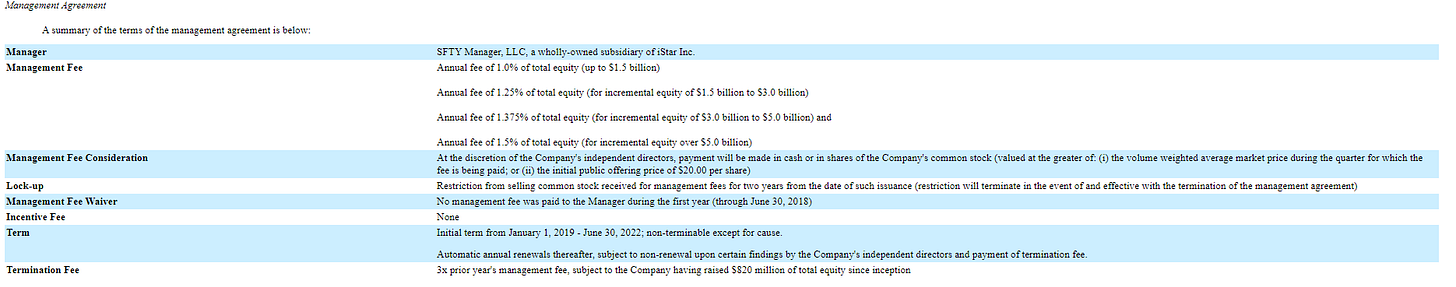

Safe is externally managed by STAR. A summary of the management agreement is below. As SAFE increases in size, STAR gets paid more (if SAFE's equity value is $1.5B, they get paid just 1%, but for every dollar over $1.5B, they get a 1.25% fee). Across all externally managed REITs, there's always an incentive for the external manager to grow the REIT, but the incentives at SAFE are perhaps the worst I've seen. STAR only gets paid on management fees (i.e. there's no incentive fee for STAR to earn from good performance at SAFE), and the management fee scales up as SAFE gets bigger.

STAR may counter this by saying they are, by far, the largest owner of SAFE (they own >60% of SAFE's equity), so their ownership stake far outweighs the management fee. That's true.... for now. But there's nothing in the management contract that requires STAR to continue to hold the equity....

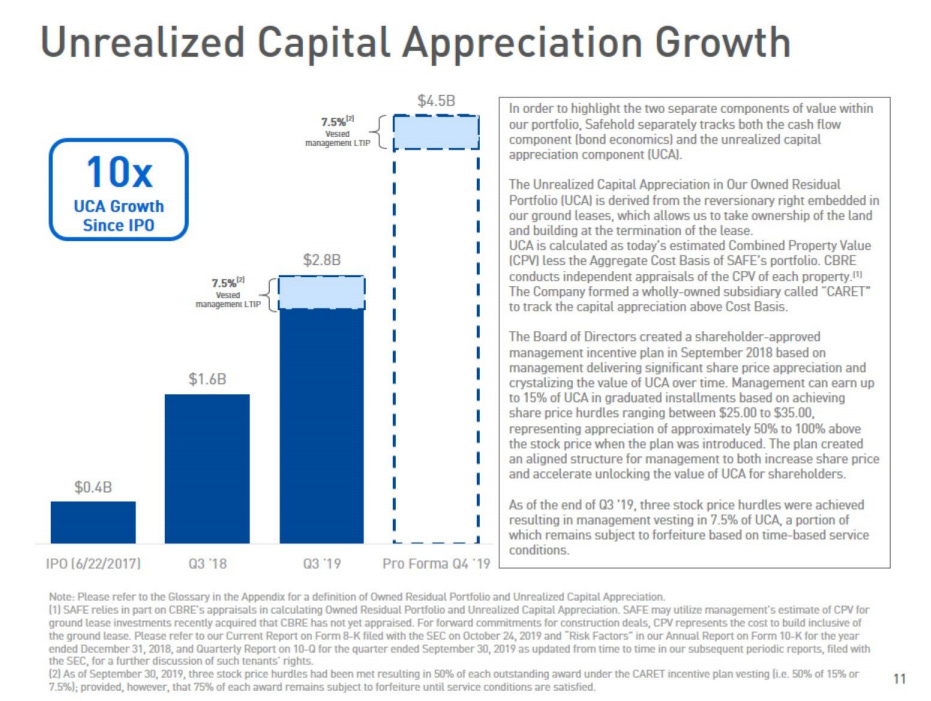

In addition to the external management contract, SAFE has adopted their "CARET" program for its executive team (who also double as STAR's executive team). You can find details of the program on p. 53 of SAFE's proxy, but the basic overview is that SAFE will capture a lot of value once all of these ground leases end and the buildings above the ground leases revert to SAFE. The CARET program is designed to track the unrealized capital appreciation from that reversion feature, and it gives 15% of the appreciation to the executive team to incentivize them to keep doing these great deals (note: the chart below says 7.5%, but the share price target has been hit so that the management team now takes 15% of appreciation). On the surface, this looks pretty innocuous, but it's actually a horrific deal for shareholders as it encourages management to do every single deal that is presented to them. Think about it: management takes 15% of the capital appreciation in every deal they do. Why should they care about the IRR for any deal they do going forward? The IRR is a problem for shareholders; management takes 15% of capital appreciation. An example might show this best: say a seller has a property worth $1B. They go to SAFE and offer to sell SAFE a ground lease for $200m, leaving the building with $800m of equity. It doesn't matter what the seller offers to pay SAFE in annual lease for that building; management is always incentivized to take that deal. In 50 years, the buildings value will revert to SAFE, and management will capture 15% of the value difference. Because property tends to appreciate over time, the whole building + land will be worth significantly more in the future than it is today. If I assume that the property appreciates at 2%/year, in 50 years it will be worth >$2.4B. SAFE's cost basis will still be $200m, and so management will get 15% * ($2.4B minus $200m) = ~$330m. For free. Yes, that's future value... but if you assume a discount rate of 5%, that's worth ~$29m in NPV today. Management just did a deal that got them paid $29m for nothing. It literally makes no difference what the seller offer to pay SAFE per year in rent, or what SAFE's IRR looks like. Management gets fabulously wealthy no matter how SAFE shareholders do.

Let's assume SAFE's projections are correct and they are buying buildings at 8-9% returns on equity. Once SAFE hits the highest fee schedule, 1.5% of that return will be going to STAR, not SAFE, through the management contract. So about 20% of the projected returns of every deal is going to STAR, and that's before considering that SAFE's management team personally takes home another 15% of the building upside form the CARET plan.

Valuation: SAFE is valued very richly. As I'll explain in a second, it's tough to say exactly how richly valued, but there's no doubt it's richly valued.

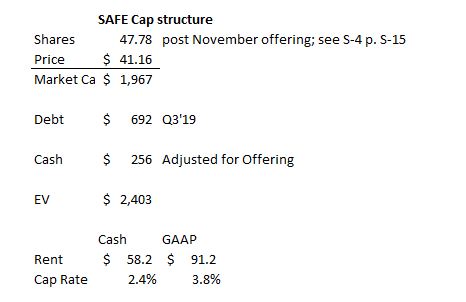

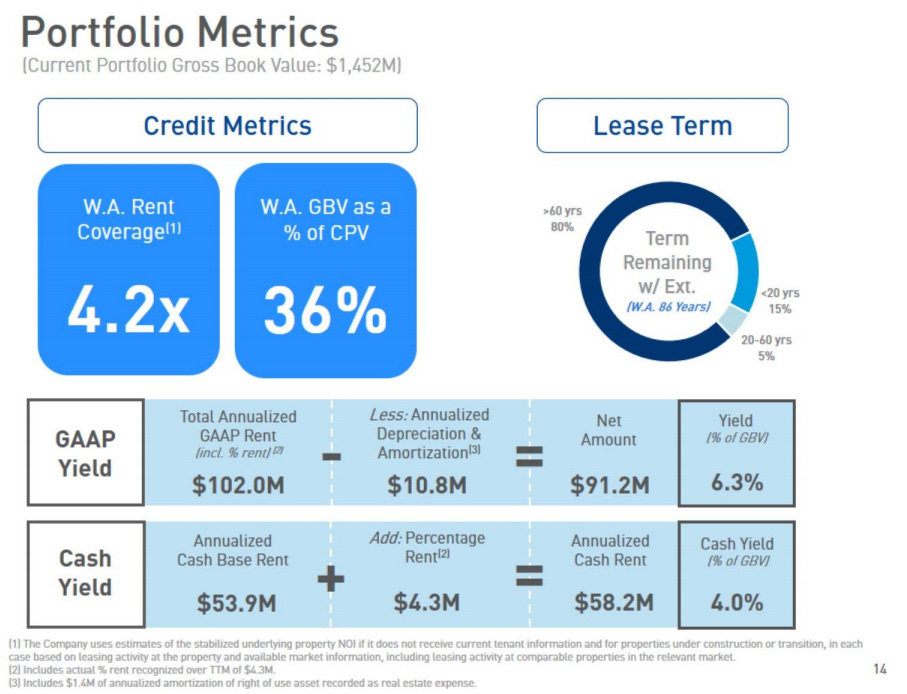

The simplest way to look at it would be to use the cap rate method: take the operating income from SAFE's properties and divide it by SAFE's EV. There is one tiny question though: should the operating income be a cash operating income (i.e. the rents it receives for the leases), or should it also include the value accrual from the property appreciating (the difference between the value of the entire property, which SAFE will take over at the end of the lease, and what SAFE paid for the lease, amortized over the life of the lease)? The former is likely too conservative as it ignores the real value from the property appreciating that SAFE will capture in the long run; however, the later may be a bit too aggressive, as that value can be really far out in the future and it may be difficult for SAFE to realize that value given how far out it is and there are no cash flow streams associated with it (I consider myself a long term investor, but 50-100 years with no potential cash flow associated with it is a really long time, and an awful lot can change in the world between now and then!). You can see SAFE presents you with both numbers (GAAP and cash rent numbers in slide below); regardless of which we use, SAFE is currently pricing at a very low cap rate (~2.4% on cash; 3.8% if we use their GAAP number). It's likely that even this is too aggressive, as valuing them off the rent number assumes zero expenses associated with the rent (and some of those expenses, like the management fee, are very real and meaningful), but as a first pass it's a nice way to show how expensive SAFE is. (Note: SAFE just did an equity raise in November; I've included the new shares out and the cash from the raise in the figure below)

But that valuation will get stale rather quickly. The chart below is from STAR's December investor deck. At the end of Q3'19, SAFE had done ~$1.5B in deals. Since then, they've committed to another $1.1B in deals. That's a huge increase; they've nearly doubled their asset base. So I'm not sure trailing metrics are super useful here, since the asset base is getting so materially reshaped.

Another interesting way of looking at SAFE? SAFE is extremely new, so almost all of their deals are brand new (particularly on a dollar weighted basis; again, see chart above). Adjusted for their recent equity offering, I have their book value at ~$22.73/share. Shares today trade for ~$41-42/share. That $18/premium you're paying over book represent one of three things: your belief that the deals they've done so far have immediately captured value that isn't captured in their book value (i.e. each lease they sign turns $1 in $2), their ability to create value through deals in the future (the exact same thing, except giving them credit for future deals), or some combination of the two. I'm skeptical that SAFE deserves any premium, but a premium this big seems pretty aggressive.

Ok, hopefully at this point I've emphasized that SAFE is expensive, its incentive system is awful for common shareholders (great for management though!), and I don't believe there's any competitive advantage that will allow them to create excess returns in the future. Let me wrap this up by hammering home that last point: the real estate market is fiercely competitive, and SAFE is competing against some of the brightest minds out there. The way the stock market currently values SAFE is signaling to every other real estate company that people are desperate for exposure to ground leases. That's going to attract competition, which will drive the returns down for SAFE. How will it attract competition? Well, let's say you're a giant office REIT today. You own five buildings worth $1B in Manhattan. Most REITs trade at a discount to NAV, but let's ignore that for a second and say you trade for a $5B EV. Well, you see that SAFE is buying ground leases for $200m and the market is instantly valuing them at $400m. Some simple financial engineering is in order: simply take those five buildings, create a ground lease similar to the one's SAFE structures, and spin those into a new company. Boom! SAFE suddenly has a publicly traded comp who can go out there and bid against them on deals, or who investors can point to as a valuation comp. There are plenty of huge real estate companies with mammoth portfolios out there. Many are controlled by super sharp asset managers (BX, BAM (disclosure: long), etc.)) who thrive on long dated fees (and who would love to manage a publicly traded vehicle like SAFE). I can promise that if SAFE continues to be valued like this, competition is coming to the space. When it does, the returns from SAFE's deals are naturally going to have to trend down. And all the incentives are there for SAFE to continue to pursue deals at any cost as the returns go down, because management will get paid regardless. Let me re-emphasize something: SAFE is a really small short for me, and shorting is risky. Do your own work. I'm not in the business of putting out exact position sizing, but to give a sense of how small this short is: the stock could trade for $100/share tomorrow (so more than a double) and it would barely be a blip on my portfolio's radar. And that's ignoring that I'm long some STAR in roughly equal measure against SAFE; STAR is relatively levered and their SAFE equity stake is currently worth more than their market cap; in addition, STAR controls SAFE's management contract, which gets more valuable as STAR goes up. So theoretically SAFE going up should result in STAR going up even more, though anything can happen in the short term. Still, despite the small sizing, I wanted to post this piece because

I thought the SAFE thesis (both the company's investment thesis and the short case) was interesting

Shorting is risky! My readers are (generally) pretty sharp, so if anyone else has done work on the company I'd love to hear it.

Odds and ends

At the beginning, I mentioned SAFE reminded me of the yieldco craze. I don't think I explicitly finished that thought, so I'll do so here. People are clearly desperate for really safe investments with long term, locked up cash flow. That helps the yieldcos a few years ago, and it's helping SAFE today. But what the wiseman does in the beginning, the fool does in the end. It was foolish to buy yieldcos (a good idea in theory, if you ignored all the awful management incentives) when they traded for twice NAV; trading for twice NAV assumes significant future value accrettive growth, and yieldcos were at their core a collection of financial assets. There's no possible accrettive future growth there unless you assume future profitable deal making, and that's a very bold bet from something as simple and commoditized as buying long dated energy assets from investment grade counterparties. Similarly, SAFE is at its core a good idea if you ignore the awful incentives, but it's silly to buy it for nearly twice NAV. It's a collection of financials assets, and there's no possible future accrettive growth from a simple collection of financial assets unless you assume future profitable deal making, which is a very bold bet for something that should be as commoditized as selling super long dated ground leasees.

With yieldcos, they kept working as long as their share price was high enough (and their implied cost of capital low enough) that they could continue to issue equity to fund accrettive acquisitions. The moment that stopped (either because their share price fell, or because they could no longer find deals large enough to budge the needle), they imploded. I suspect a similar dynamic is at work with STAR. The nice news is the commercial real estate market is huge, so as long as their share price remains high they won't run out of accrettive deals for a long, long time. But that's a big assumption, and it will require them to sell a heck of a lot of equity to keep funding deals....

I mentioned that I'm long STAR. The value of STAR's SAFE shares are worth more than STAR's market cap today; unfortunately, STAR is pretty levered, and I'm still doing work to try to get comfortable with the rest of their asset base. My initial takeaway is that I don't love the other assets, but they're not complete garbage. My basic thought here is the value of their SAFE shares + the management contract are so significant that as long as I'm right that the rest of STAR's assets aren't awful, I'm fine. Again, this is a super small position, so it's still a work in progress. I may post an update as I get deeper into it, but I wanted to get this post out now before I left for the honeymoon.

Let's say I'm wrong about everything in this article, and SAFE deserves a premium because they can turn every dollar they invest into $2, and no one else can replicate what they do. That's fantastic.... but STAR is the actual operator / manager who goes and finds those deals. They would have all the intellectual assets. They'll get the major upside from the management contract and from constantly raising equity. I tend to think most of the future gains will flow to the manager, not the asset, when the asset is valued at this big a premium.

SAFE's asset base obviously has an incredibly long duration. That's been great this year, as interest rates have come down quite a bit. I think SAFE is interesting as a short because of that: if interest rates continue to go down, SAFE probably continues to go up just given that duration. But if rates stall, I think SAFE comes down given how much value the market is currently assigning to SAFE's future profitable growth. And if rates go up......

A common red flag in banking or any type of financial company is a company that grows its asset base really quickly. The reason is pretty simple: if you grow your asset base rapidly, it can look great in the short run. But you might be growing it because you're exposed to a bunch of risks other people want take and you don't realize that, or the quick growth might be designed to cover material deterioration in the legacy asset base. I don't think that's the case here, but I wanted to highlight it because SAFE is growing just so freaking quickly (again, they've almost doubled their asset size since the end of Q3!).

I wasn't sure how to quantify this, but another red flag I see here is management just seems a bit arrogant. For example, someone asked them the primary risks to their business. They basically responded that the risks were in the past; it was just a question of how fast they could scale the business now. And that they had 2.5 years of secret sauce that would prevent anyone from competing with them. That type of arrogance seems a red flag, and (again) I'm not sure why the value wouldn't accrue to the manager (STAR) instead of the asset (SAFE) if the value was really in the secret sauce / institutional knowledge.

Again, the STAR piece of this is still a work in progress, but I am a little surprised that STAR could be that arrogant about deal making with their historical track record / share price. If you think I'm wrong on that take, I'm very open to hearing otherwise!