Some things and ideas: July 2019

Some random thoughts on articles that caught my attention in the last month. Note that I try to write notes on articles immediately after reading them, so there can be a little overlap in themes if an article grabs my attention early in the month and is similar to an article that I like later in the month. Podcast:

You can find this month's Rangeley Capital Podcast here. On it, we talk about David Einhorn / Greenlight Capital's Q2'19 letter and its comparison of Chewy to Pets.com (I also tweeted some thoughts on the Chewy's shareholder letter). Then we discuss Beyond Meat's unique secondary offering (Matt Levine covered it extremely well here), and how it took both a fire and fraud to cause the first bank failure of the year.

Monthly value theory ponderings: position sizing and conviction

One of the things I struggle most with is position sizing. How do you decide if something is worth a 1% position versus a 5% or 10%? I've toyed with a variety of ways of doing this, but I don't think I've come close to solving the right way to do size stocks.

I know some investors who say "nothing smaller than a 5% position." I have a lot of understanding for that sizing strategy, and I increasingly try to avoid smaller sized names. Still, avoiding 1% names entirely feels like depriving yourself of the shot to buy really mispriced optionality (i.e. I probably wouldn't want something as levered as WOW (disclosure: long) to be a 5% position, but for a smaller position I think it presents a really interesting risk reward. Pre-approval biotech names can offer fantastic upside / downsides, but given the huge risk of their drug failing and becoming a zero it's tough to take a bigger position).

Moving away from 1% positions, let's say you've done a ton of work on a stock and decided you want to buy a large position. How do you determine if that position should be a 5% versus 10% versus 15% position?

I know some investors who say they do it based on IRR. A 5% position has to have a 20% IRR to their base case, a 10% position a 30% IRR to base case, etc. I understand the logic there, but I don't think it's fair on a bunch of levels. Just to pick one: I think that encourages you to invest in more levered and more cyclical companies (i.e. a really levered company could offer a base 25% return but have the possibility of a zero, while the same company with zero leverage might offer a base return of 10% with a downside return of 5%).

On a related note, I remember when Fortune's Formula came out, sizing positions based on the Kelly criterion got really popular. I think a lot of investors still do some type of modified Kelly formula for their positions, but I'm a bit skeptical of this sizing too (and I think those investors must be too; running a "modified Kelly" or a "half Kelly" as I've heard so many people run is simply an admission that the Kelly formula isn't capturing everything a portfolio manager needs it to capture). I think Kelly is really good if you're running a pure risk / merger arbitrage book, but if you're running events or special situations I think the Kelly criterion starts to run into a few problems. First, outcome ranges for most stocks / businesses are pretty wide, and I think blending a variety of outcomes into the Kelly formula is difficult and very easily runs into "garbage in, garbage out" issues. Second, maybe it's because I haven't refined my Kelly formula in a while, but I generally found Kelly formulas would encourage me to invest in riskier companies than I generally meant to (i.e. invest in a more levered company versus an under-levered company), and I found it difficult to capture things that gave me conviction in companies (i.e. I couldn't think of a way to capture trusting a management teams' capital allocation skills, so that they were more likely to buyback stock when it was cheap or that they wouldn't do horrible acquisitions). An example might show this best: say I thought company A (a steel company) was worth $50 and its stock currently traded for $30. That's a large discount, but the issue with a steel company is that it probably has no profitable growth opportunities so your IRR is really dependent on how quickly the gap between IV and share price closes (if it closes in the next year, you're a genius; if it closes 10 years from now, you generated basically no alpha). Compare that to company B, which I think is worth $50 and currently trades for $40, but has a ton of profitable reinvestment opportunities and a top class management team so that I think they can compound value above their cost of capital going forward. I generally found the Kelly formula would tell me to lean towards situations like company A, but with some experience I think company B (a bit more expensive, but still undervalued and with more "compounder" potential) generally make for the best bets (I'm not breaking new ground here; this is the classic "the stock price matches the ROIC over a long period of time" Charlie Munger quote).

I don't have any definitive answers here. Over time, I think I've gotten better about sizing, but I think I still have a long way to go here. If you have any thoughts on the subject, I'd be interested!

A slight tangent to position sizing, but something I've thought for a while (and think I may have talked around before): the longer I invest, the more I think the most important part of this job / doing the work around this job is developing the conviction to hold an investment thesis. Let me explain: there is absolutely no stealing in investing, and at times that can feel unfair. If I spend weeks doing work on an idea and post it on here, someone could read the idea, say "wow, that's interesting, I agree," buy the stock, and generate the same returns as me (or generate better returns if they get the idea at a better cost / concentrate heavier into the idea). For a long time, that struck me as unfair, but increasingly it doesn't bother me. Over the long run, I think a person who "steals" ideas will do substantially worse than a person who develops their own ideas simply because the "idea thief" won't have conviction in the idea, and that will lead to incredibly sub-optimal trading. Let's say the company announces softer earnings and the stock's down 20%. Is that a buying opportunity or a sign the thesis is failing? I'm going to guess the person who's done work / has conviction on the idea is going to have a much better chance of correctly calling which it is. Or what if the stock is up ~20% in the month after you buy on limited news? I'm going to guess an idea thief is a lot more likely to say "no one ever went broke taking a profit" and sell the stock, which is nice.... but if you've done a lot of work and have conviction that the upside is still 5x higher, selling at a 20% gain isn't going into your mindset. You're playing for a much bigger return, and I think without the conviction of having done a lot of deep work you're not going to be able to hold out for that payoff.

For me personally, I think the biggest drawback to my returns over the past few years has come from doing some work on a company, taking a small position, seeing the stock go up a little bit and selling at a small profit only to see the stock go up another 50%+. Not only was my selling tax inefficient, but if I had done enough work to get really convicted on an idea I could have both taken a larger initial position size and/or held on for bigger gains.

Speaking of position sizing and conviction, I think the two are the a big reasons why "best ideas" funds generally fail. A best ideas fund is a fund that finds ~10 managers, takes the top pick from each, and throws each into a fund. It's a really sexy sales pitch ("We're going to find 10 guys who are super smart, have a history of beating the market / we think are super likely to do so going forward, and invest in only their top idea."), but in practice I think the funds have serious issues.

The most glaring issue is the incentive issue. In general, top ideas funds pay the managers whose ideas they "steal" a percentage of the upside from their ideas. So let's say you come to me and say, "Andrew, we think you're super smart, and we want you to be a part of our best ideas fund. Give us your best idea and we'll give you 10% of the upside from any incentive fees we make on it." You've just given me a free call option on my idea, and it behooves me to maximize the value of that call option by pitching something as risky as humanly possible. Say I had two favorite ideas right now: a small biotech that is awaiting on FDA approval and could either go up 5x or go to zero, and a super safe liquidation that will return 10% in the next two months. It's entirely possible that the liquidation is a much better risk / reward, but my incentives are to pitch the biotech. In fact, it would make more sense for me to pitch the small biotech even if the market is dramatically overpricing the odds of approval (in the 5x versus 0x scenario, the market is pricing in ~20% chance of approval; even if I thought the true odds were 5-10% this incentive structure would encourage me to pitch the biotech).

Portfolio sizing is another similar but related issue. Say you're doing a best ideas fund with five mangers; do you make each managers' idea a 20% position? Again, seems nice in practice but if each of the ideas has dramatically different risk levels it can get pretty crazy. What if one of your managers invests in a lot of riskier, smaller companies and generally takes 3-5% positions, while another manager takes huge, concentrated swings in relatively safer companies (say, four positions each making up 25% of the portfolio). If you pull each of those managers top ideas equally, you're going to be WAY too exposed to the riskier managers top idea, right?

And how are you going to deal with stock price movements in a best ideas fund? If I pitch a best idea and it's down 20%, what does the fund do? Does it sell down other positions to buy more of my idea / to keep a constant weighting? Or does it let the position diminish over time? The former risks buying all the way down for a position that eventually blows up (if you start with a 2% position and "double down" every time the stock goes down 10%, you can relatively quickly find yourself having put >20% of your capital into a stock with rapidly deteriorating fundamentals / an investment thesis you simply got wrong), while the later risks becoming too concentrated in your other ideas or missing a buying opportunity when the market panic sells a stock.

A follow up on HHC (disclosure: long)

Earlier this month I posted a "quickie idea" on HHC and wondered if the huge spike on its strategic alternative announcement suggested the market was systematically mispricing "land banks".

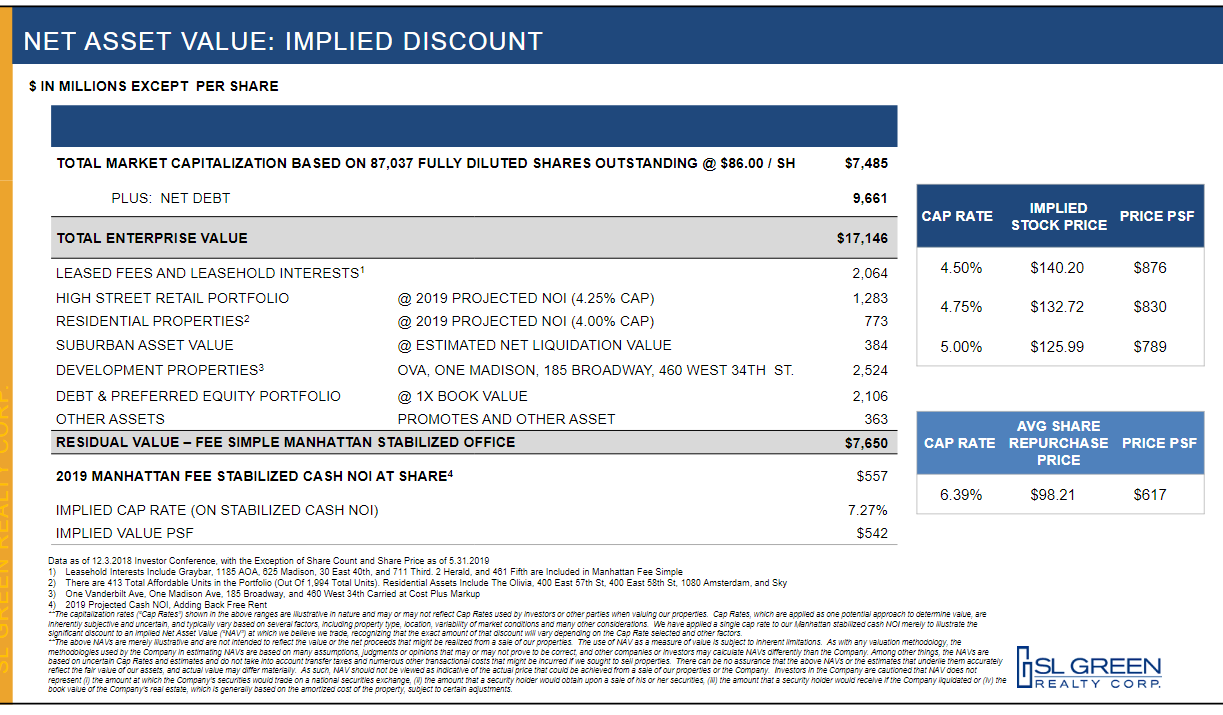

About a week later I was this quote on SLG's earnings call, where they argue that people prefer to invest in private real estate deals versus public market deals because private market deals allow them to avoid volatility / mark to market (as Modest Proposal put it, "illiquidity premiums are the new liquidity premiums"). That got me wondering: was the huge HHC "pop" an example of the market systematically underpricing land banks, or was it an example of mispricing public real estate assets? It's possible it's the later, and if SLG (or any of their peers that argue they trade at a huge discount to NAV) wanted to close the gap, they could do so rapidly and unlock a ton of value by running a sales / liquidation process... and if that's the case, all of these would be obvious activist targets (SLG, for example, argued in the slide below (from their June investor deck) that their intrinsic value is >$125/share, but their shares currently trade for ~$81; an activist could come in and rapidly close that gap by selling off buildings or forcing a sales process).

Vornado (VNO) has been arguing something similar for the past few years (their most recent shareholder letter included a stock price versus NAV comparison that suggested the stock price divorced from their NAV ~4 years ago and the divergence has been widening since); I actually mentioned VNO last year because they were making a similar argument while refusing to buyback shares and I thought that was insane. (as long as I'm linking to my own tweets, the bear case for NYC office space (that it performs like NYC hotels over the past few years) is always a question in my mind when I glance at these companies; I've never done enough work on them to get a good answer and I suspect the hotel / office markets are different fora host of reasons, but I do think it's a good question and I'm always worried investing in something that's had a great multi-decade run (as NYC office in general has) and seems somewhat indestructible / inevitable).

Of course, it's possible SLG / VNO (and their peers) are wrong on what their intrinsic value is. Or it's possible the market is simply discounting other things (for example, maybe the market is applying a discount because it thinks future capital allocation will destroy value). But when I saw that SLG quote, it reminded me of what HHC had been saying for years (that their market price was way under NAV), and I thought it might be possible that the "landback discount" HHC showed may be more widespread in the public real estate sector.

Some book recommendations / request for recommendations

I tweeted this out, but I recently went on a "fraud" book reading spree and read Billion Dollar Whale (1MDB), Smartest Guys in Room (Enron), Bad Blood (Theranos), and Wizard of Lies (Madoff). I really enjoyed my "foray" into the world of fraud and would recommend all of those books; if you have any recommendations for books on fraud I should add to that list / read I would be very interested (I will try to post good recommendations in next month's links post; I already got a bunch on twitter so I have a very full reading list!).

There were plenty of lessons to be learned from reading all of those, but for me I think the three key takeaways were

Political capture: it's crazy to me how consistently red flags were raised at all of these frauds. People warned regulators that there was something wrong at all of these companies years before they ultimately came crashing down, but regulators were reluctant to investigate or do anything because the fraudsters often had deep relationships with powerful political figures (or at least ties to powerful political figures strong enough that regulators were hesitant to dig too deep).

How quickly it all comes apart: In all of the cases, the frauds come tumbling apart extremely rapidly. Enron's stock price is instructive: it peaked about a year in mid to late 2000, and was a complete zero by mid to late 2001, and Enron actually seems to have dragged on larger than most of these once they start to really come apart. Many of them appear to be on top of the world until almost literally the day the fraud unravels and they are taken away in handcuffs.

Running a fraud is stressful: I'm not exactly breaking new ground here, but running a fraud seems quite stressful. I found myself more stressed than usual just reading about the fraudsters and all of the lies they told / balls they had to keep juggling. I would wake up in the middle of night panicked just having read about them. One of the biggest pities about the fraudsters is that there's no doubt they have talent (a knack for selling in particular); it's a shame that talent is wasted on fraud instead of somewhere it could actually create value.

Emotionally, I think the most devastating of the books was the Madoff book. The last third of it goes through the fraud's fallout, how many people were invested in funds that they had no idea had anything to do with Madoff, and how many people have their world rocked by the fraud. I also didn't realize the complexities behind wrapping up Ponzis and getting money back to victims, and how the "cash in cash out" method makes the most sense but can be just devastating for people who had been invested in the fraud since the beginning (this article partly covers some of the issues, but I'd suggest reading the book for more). Ugh.

Sports media update: A core tenant of the monthly update: continued highlights of the increasing value of sports rights (mainly because of my love of MSG (disclosure: Long)).

Former NBA Head David Stern on how sports betting can save TV rights

Move over Nevada: New Jersey is the Sports Betting Capital of the Country

Is the knicks' James Dolan the Worst Owner in Professional Sports? (He's awful, and he should definitely #selltheteam, but he's probably not even the worst in the NBA. As far as I know, he hasn't filled his GM's office with pooping goats, nor do they have a history of selling their second round picks just because their owner wants to make some extra pocket change).

Billionaire Blavatnik wants a piece of America's biggest sport (DAZN looking at NFL rights)

Other things I liked

Media legend barry diller (interview on CNBC)

I really liked this line on the only people who watch advertisements being the ones who can't afford them

Match CEO on Innovating in a fast changing industry (disclosure: long MTCH through IAC)

The Downside of 5G: Overwhelmed Cities, Town Up Streets, a decade until completion

Over the last 20 years, Lion King Broadway has made more money than Star Wars

Music streaming services tap Apple Music, Spotify Tap Live events

Everyone wants to be the next Game of Thrones

Coming to a streaming service near you: shows costing as much as big-budget movies

Netflix won't be felled by Recession (Netflix Misunderstandings, Pt. 8)

Stranger Things brings a lot of ex-Netflix subs back to the service

Shari Redstone's merged CBS / VIA vision begins to take shape

After 'Office' and 'Friends' Mega-deals, stars want their slice of streaming money

CBS blackout on DTC is what's wrong with the TV Market

I tweeted this out, but on their earnings call AT&T described their blackout of CBS and Nexstar as very different. I don't understand why, and would be curious if anyone could tell me. Remember, the CBS blackout is only of the local markets CBS owns, not all of CBS, so it seems like a CBS blackout and NXST blackout are basically the same. In fact, given CBS all-access gives online access to CBS, and NXST owns several stations that are not CBS branded (i.e. NBC, ABC, etc.), you could argue that NXST stations are harder to get access to than CBS stations. Why does AT&T say the blackouts are different? (Admiral Holdco suggested the difference is the CBS negotiation includes Network on demand content, which makes some sense to me but I would be surprised if on demand is so valuable that it creates that big of a negotiating dynamic gap.)

Inside the conflict at Walmart threatening its fight with Amazon (loved this article; classic example of how hard it is for a legacy company to navigate a huge tech shift / stomach the losses necessary to do so)